Security News

Research

Data Theft Repackaged: A Case Study in Malicious Wrapper Packages on npm

The Socket Research Team breaks down a malicious wrapper package that uses obfuscation to harvest credentials and exfiltrate sensitive data.

rspec-expect_to_make_changes

Advanced tools

expect {…}.to make_changes(…)This small library makes it easy to test that a block makes a number of changes, without requiring

you to deeply nest a bunch of expect { } blocks within each other or rewrite them as change

matchers.

Sure, you could just write add a list of regular RSpec expectations about how the state should be before your action, and another list of expectations about how the state should be after your action, and call that a "test for how your action changes the state".

expect(thing.a).to eq 1

expect(thing.b).to eq 2

expect(thing.c).to eq 3

perform_change

expect(thing.c).to eq 9

expect(thing.b).to eq -2

expect(thing.a).to eq 0

But often your expectations occur in pairs: a "before" and an "after": one for the state of something before the action and a matching expectation for the state of the same thing after the action.

As the number of pairs grows, it can be quite hard for the reader of your test to see which expectations are related, and how. It can also be hard for the writer of the test to maintain, esp. if they are relying on things like the order and proximity of the expectations alone to indicate a connection between related before/after expectations.

The make_changes (and before_and_after) matchers provided by this library give you a tool to

make it explicit and extremely clear that those 2 expectations are a pair that are very tightly

related.

So instead of the above, you can rewrite it as explicit pairs like this:

expect {

perform_change

}.to make_changes([

->{ expect(thing.a).to eq 1 },

->{ expect(thing.a).to eq 0 },

], [

->{ expect(thing.b).to eq 2 },

->{ expect(thing.b).to eq -2 },

], [

->{ expect(thing.c).to eq 9 },

->{ expect(thing.c).to eq 9 },

])

or, using change matchers, like this:

expect {

perform_change

}.to make_changes(

change { thing.a }.from(1).to(0),

change { thing.b }.from(2).to(-2),

change { thing.c }.from(3).to(9),

)

(or any combination of [before_proc, after_proc] arrays and change matchers)

RSpec already provides a built-in matcher for expressing changes expected as a result of executing a block. And it works great for specifying single changes. You can even use it for specifying multiple changes:

expect {

expect {

expect {

perform_change

}.to change { thing.a }.from(1).to(0)

}.to change { thing.b }.from(2).to(-2)

}.to change { thing.c }.from(3).to(9)

Granted, that makes it much clearer at a quick glance what changes are expected by your action. But it also has some drawbacks:

expect(something).to eq something expectations — into a very different

change() matcher style.RSpec provides a pretty good solution to the nesting problem via its compound (and/&) matchers

that let you combine several matchers together and treat them as one, so you can actually simplify

that to just a single event block using just built-in RSpec:

expect {

perform_change

}.to (

change { thing.a }.from(1).to(0) &

change { thing.b }.from(2).to(-2) &

change { thing.c }.from(3).to(9)

)

change is often all you need for changes to primitive values. But it isn't always enough for

doing more complex before/after checks. And it's not always convenient to rewrite existing

expectations to a different (change) syntax.

make_changes gives you the flexibility to either leave your before/after expectations as "regular"

expects or use the change() matcher style of expecting changes.

This flexibility gives you the power and flexibility to lets you express some things that you simply

couldn't express if you were limited to only the change matcher, such as things that you would

normally use another specialized matcher for, such as expectations on arrays or hashes:

expect {

perform_change

}.to make_changes([

->{ expect_too_close_to_pedestrians(car) },

->{ expect_sufficient_proximity_from_pedestrians(car) },

], [

->{ expect(instance.tags).to match_array [:old_tag] },

->{ expect(instance.tags).to match_array [:new_tag] },

], [

->{

expect(team.members).to include user_1

expect(team.members).to_not include user_2

},

->{ expect(team.members).to include user_1, user_2 },

])

Although you can define aliases and negated matchers to do things like this:

RSpec::Matchers.alias_matcher :an_array_including, :include

RSpec::Matchers.define_negated_matcher :an_array_excluding, :include

array = ['food', 'water']

expect { array << 'spinach' }.to change { array }

.from( an_array_excluding('spinach') )

.to( an_array_including('spinach') )

, it may not always be possible, and requires you to define the needed matchers. Whereas

make_changes allows you to simply use the "regular" matchers that you already know and love:

array = ['food', 'water']

expect { array << 'spinach' }.to make_changes([

->{ expect(array).not_to include 'spinach' },

->{ expect(array).to include 'spinach' },

])

It can sometimes be more readable or maintainable if you can just use/reuse regular expectations for your before/after checks.

You might not even be checking for a change. You might simply want to assert that some invariant still holds both before and after your action is performed.

expect {

perform_change

}.to check_all_before_and_after([

->{ expect(car).to_not be_too_close },

->{ expect(car).to_not be_too_close },

])

That would be difficult or impossible to express using change matchers, since it's not a change.

before_and_after matcherIn the examples above, if you pass an array to make_changes as one of the "expected changes", it

actually converts that to a before_and_after matcher, and then ands together all of the

"expected changes" into a single Compound::And matcher.

If you wanted to, you can also use before_and_after directly, like:

expect { @instance.some_value = 6 }.to before_and_after(

-> { expect(@instance.some_value).to eq 5 },

-> { expect(@instance.some_value).to eq 6 }

)

Add this line to your application's Gemfile:

gem 'rspec-make_changes'

And then execute:

$ bundle

Or install it yourself as:

$ gem install rspec-make_changes

After checking out the repo, run bin/setup to install dependencies. Then, run rake spec to run the tests. You can also run bin/console for an interactive prompt that will allow you to experiment.

To install this gem onto your local machine, run bundle exec rake install. To release a new version, update the version number in version.rb, and then run bundle exec rake release, which will create a git tag for the version, push git commits and tags, and push the .gem file to rubygems.org.

Bug reports and pull requests are welcome on GitHub at https://github.com/TylerRick/rspec-make_changes.

FAQs

Unknown package

We found that rspec-expect_to_make_changes demonstrated a not healthy version release cadence and project activity because the last version was released a year ago. It has 1 open source maintainer collaborating on the project.

Did you know?

Socket for GitHub automatically highlights issues in each pull request and monitors the health of all your open source dependencies. Discover the contents of your packages and block harmful activity before you install or update your dependencies.

Security News

Research

The Socket Research Team breaks down a malicious wrapper package that uses obfuscation to harvest credentials and exfiltrate sensitive data.

Research

Security News

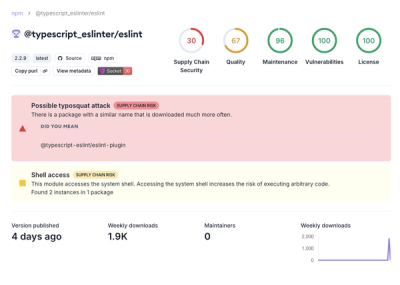

Attackers used a malicious npm package typosquatting a popular ESLint plugin to steal sensitive data, execute commands, and exploit developer systems.

Security News

The Ultralytics' PyPI Package was compromised four times in one weekend through GitHub Actions cache poisoning and failure to rotate previously compromised API tokens.