Research

Security News

Lazarus Strikes npm Again with New Wave of Malicious Packages

The Socket Research Team has discovered six new malicious npm packages linked to North Korea’s Lazarus Group, designed to steal credentials and deploy backdoors.

@bodiless/fclasses

Advanced tools

Allows for the injection of functional class into components.

The Bodiless FClasses Design API is designed to facilitate the implementation of a Design System in a React application. Before diving into the technical details below, it might make sense to read our high level overview of Design Systems in Bodiless to better understand the general patterns at work.

At a high level, this API expresses Design Tokens as React higher-order components, and provides utilities which allow you to apply them to both simple elements and compound components. In most cases, the design token HOC's leverage "atomic" or "functional" CSS, defining units of design as collections of utility classes.

A compound component using this API will expose a styling API (a design prop) which

describes the UI elements of which it is composed. Consumers then supply a

list of higher-order components which should be applied to each element to modify

its appearence or behavior. The framework allows nested wrapping of components

to selectively extend or override individual elements. It also provides a tool

for adding and removing classes to/from individual elements.

Use of this API allows composed components to expose a styling API which remains consistent even when the internal markup of the component changes. Consumers of those components can then sustainably extend and re-extend their look and feel, with less danger of breakage when the underlying component changes.

In Bodiless, you implement design tokens as React higher-order components (HOC). Applying the HOC to a component is equivalent to styling that component with a token:

const ComponentWithStyles = withMyStyles(Component);

This pattern should be familiar to those who have worked with CSS-in-JS libraries like Styled Components or Emotion.

Any HOC can be used as a token, and tokens can be composed using normal functional programming paradigms (eg Lodash flow):

const withComposedToken = flow(

withToken1,

withToken2,

);

However, Bodiless provides a token composition utility which adds some additional functionality:

This is intended to promote design-system thinking when defining tokens, by encouraging us to think about the structure and organization of tokens as we implement them. It also facilitates implementation of tools which allow browsing the design system (eg StorybooK), and eases the process of extending or customizing composed tokens without fully recomposing them.

In general, you can use flowHoc to compose tokens the same way you

would use Lodash flow, eg:

const withComposedToken = flowHoc(

withToken1,

withToken2,

);

However, there are a few key differences:

Token metadata are properties which can be attached to tokens to help organize them and understand their structure. When a token is applied, its metadata will also be attached to the component to which it is applied. If a composed token is applied, metadata from all constituents will be aggregated and attached to the target component. See below for some examples.

In addition to a normal HOC, a Token can also be a "filter". A filter is a token which, when composed with other tokens, removes any which match certain criteria. Filters are usually defined to test the metadata attached to other tokens. So, for exmple, you can compose a token which removes all 'Color' tokens and adds a new one.

Note that while metadata from all constituent tokens are aggregated and attached to the component to which a composed token is applied, the composed token itself does not have the metadata of its constituents; if it did, it would be much harder to filter. Think of the metadata attached to a Token as that portion of the final metadata which it will contribute.

It's easy enough to get the aggregated metadata, eg:

const finalMeta = pick(myToken(Fragment), 'categories', 'title', ...);

Given

const asBold = flowHoc(

addClasses('font-bold'),

{ categories: { Style: ['Bold'] } },

);

const asTextBlue = flowHoc(

addClasses('text-blue-500'),

{ categories: { TextColor: ['Blue'] } },

);

const asTextRed = flowHoc(

addClasses('text-red-500'),

{ categories: { TextColor: ['Red'] } },

);

// Same as:

// const asTextRed = flowHoc(addClasses('text-red-500'));

// asTextRed.meta = { categories: { TextColor: ['Red'] } };

const asBgYellow = flowHoc(

addClasses('bg-yellow-500'),

{ categories: { BgColor: ['Yellow'] } },

)

const asHeader1 = flowHoc(

asTextBlue,

asBold,

asBgYellow,

{ categories: { Header: ['H1'] } },

);

const Header1 = asHeader1(H1); // `H1` is a version of 'h1' stylable with fclasses, see below.

Then

<Header1 /> === <h1 className="text-blue bg-yellow-500 font-bold" />

// The component itself includes aggregated metadata from all composed tokens...

Header1.categories === {

TextColor: ['Blue'],

BgColor: ['Yellow'],

TextStyle: ['Bold'],

Header: ['H1'],

};

// ... but the token itself does not.

asHeader1.meta === {

categories: {

Header: ['H1'],

}

}

And given

const asRedHeader1 = flowHoc(

asHeader1,

asHeader1.meta, // We are creating a variant of asHeader1, so propagate its meta.

// The following creates a "filter" token. Note this must be applied after asHeader1

withTokenFilter(t => !t.meta.categories.includes('TextColor')),

// Replace the color with red. Note this must be applied after the filter.

asTextRed,

);

const RedHeader1 = asRedHeader1(H1);

then

<RedHeader1 /> === <h1 className="font-bold text-red-500 bg-yellow-500" />

// Our new token has the metadata of `asHeader1` only because we propagated it explicitly.

asRedHeader1.meta === {

categories: {

Header: ['H1'],

},

};

RedHeader1.categories === {

TextColor: ['Red'],

BgColor: ['Yellow'],

TextStyle: ['Bold'],

Header: ['H1'],

};

Order is important

As you can see from the examples above, the order in which you compose tokens can be significant, especially when applying filters.

flowHoccomposes tokens in left-to-right order (Lodashflowas opposed toflowRight).

This library was developed to support a styling paradigm known as "atomic" or "functional" CSS. There are many excellent web resources describing the goals and methodology of this pattern, but in its most basic form, it uses simple, single-purpose utility classes in lieu of complex CSS selectors. Thus, for example, instead of

<div class="my-wrapper">Foo</div>

.my-wrapper {

background-color: blue;

color: white;

}

the functional css paradigm favors

<div class="bg-blue text-white">Foo</div>

.bg-blue {

background-color: blue;

}

.text-white {

color: white;

}

Usually, a framework is used to generate the utility classes programmatically. Tachyons and Tailwind are two such frameworks. All the examples below use classes generated by Tailwind.

The FClasses API in this library provides higher-order components which can be

used to add and remove classes from an element. They allow a single element

styled using functional utilty classes to be fully or partially restyled --

prserving some of its styles while adding or removing others. For example:

const Div = stylable<HTMLProps<HTMLDivElement>>('div');

const Callout = addClasses('bg-blue text-white p-2 border border-yellow')(Div);

const SpecialGreenCallout = flow(

addClasses('bg-green'),

removeClasses('bg-blue'),

)(Callout);

The higher order components are reusable, so for example:

const withRedCalloutBorder = flow(

addClasses('border-red'),

removeClasses('border-yellow),

);

const RedBorderedCallout = withRedCalloutBorder(Callout);

const ChristmasCallout = withRedCalloutBorder(SpecialGreenCallout);

and they can be composed using standard functional programming techniques:

const ChristmasCallout = flowRight(

withRedCalloutBorder,

asSpecialGreenCallout,

asCallout,

)('div');

stylable()In order to use addClasses() or removeClasses(), the target component must

first be made stylable. That is:

const BlueDiv = addClasses('bg-blue')('div');

will not work (and will raise a type error if using Typescript). Instead, you must write:

const Div = stylable<HTMLProps<HTMLDivElement>>('div');

const BlueDiv = addClasses('bg-blue')(Div);

or, if you prefer:

const BlueDiv = flowRight(

addClasses('bg-blue'),

stylable,

)('div');

stylable() when applied to intrinsic elements.When using typescript in the above examples, we must explicitly

specify the type of our stylable Div because it cannot be inferred from the

intrinsic element 'div'.

removeClasses() can only remove classes which were originally added by

addClasses(). Thus, for example:

const BlueDiv = ({ className, ...rest }) => <div className={`${classname} bg-blue`} {...rest} />;

const GreenDiv = removeClasses('bg-blue').addClasses('bg-green')(BlueDiv);

will not work, because the bg-blue class is hidden inside BlueDiv and not

accessible to the removeClasses() HOC. Instead, use:

const BlueDiv = addClasses('bg-blue')(Stylable('div'));

const GreenDiv = removeClasses('bg-blue').addClasses('bg-green')(BlueDiv);

removeClasses() with no arguments to remove all classesconst Button: FC<HTMLProps<HTMLButtonElement>> = props => <button onClick={specialClickHandler} type="button" {...props} />;

const StylableButton = stylable(Button);

const OceanButton = withClasses('text-green bg-blue italic')(StylableButton);

const DesertButton = withoutClasses().withClasses('text-yellow bg-red bold')(OceanButton);

This is useful when you don't have access to the original, unstyled variant of the component.

The Design API provides a mechanism for applying higher order components (including those provided by the FClasses API) to individual elements within a compound component.

Consider the following component:

const Card: FC<{}> = () => {

return (

<div className="wrapper">

<h2 className="title">This is the title</h2>

<div className="body">This is the body</h2>

<a href="http://foo.com" className="cta">This is the CTA</a>

</div>

);

)

With the Design API, rather than providing classes which a consumer can style using CSS, we provide a way for consumers to replace or modify the individual components of which the Card is composed:

export type CardComponents = {

Wrapper: ComponentType<StylableProps>,

ImageWrapper: ComponentType<StylableProps>,

ImageLink: ComponentType<StylableProps>,

Image: ComponentType<StylableProps>,

ContentWrapper: ComponentType<StylableProps>,

Title: ComponentType<StylableProps>,

Body: ComponentType<StylableProps>,

Link: ComponentType<StylableProps>,

};

type Props = DesignableComponentsProps<CardComponents> & { };

const CardBase: FC<Props> = ({ components }) => {

const {

Wrapper,

ImageWrapper,

Image,

ImageLink,

ContentWrapper,

Title,

Body,

Link,

} = components;

return (

<Wrapper>

<ImageWrapper>

<ImageLink>

<Image />

</ImageLink>

</ImageWrapper>

<ContentWrapper>

<Title />

<Body />

<Link />

</ContentWrapper>

</Wrapper>

);

};

Here we have defined a type of the components that we need, a starting point for those components and then we have create a componant that accepts those compoents. Next we will combine the Start point as well as the CardBase to make a designable card that can take a Design prop.

const cardComponents: CardComponents = {

Wrapper: Div,

ImageWrapper: Div,

ImageLink: A,

Image: Img,

ContentWrapper: Div,

Title: H2,

Body: Div,

Link: A,

};

const CardDesignable = designable(cardComponents, 'Card')(CardBase);

Note the second parameter to designable above; it is a label which will be used

to identify the component and its design keys is in the markup. This can make

it easier to locate the specific design element to which styles should be

applied, for example:

<div bl-design-key="Card:Wrapper">

<div bl-design-key="Card:ImageWrapper">

...

Generation of these attributes is disabled by default. To enable it, wrap the section

of code for which you want the attributes generated in the withShowDesignKeys HOC:

const CardWithDesignKeys = withShowDesignKeys()(CardDesignable);

or, to turn it on for a whole page, but only when not in production mode,

const PageWithDesignKeys = withDesignKeys(process.env.NODE_ENV !== 'production')(Fragment);

<PageWithDesignKeys>

...

</PageWithDesignKeys>

A consumer can now style our Card by employing the withDesign() API method to

pass a Design object as a prop value. This is simply a set of higher-order

components which will be applied to each element. For example:

const asBasicCard = withDesign({

Wrapper: addClasses('font-sans'),

Title: addClasses('text-sm text-green'),

Body: addClasses('my-10'),

Cta: addClasses('block w-full bg-blue text-yellow py-1'),

});

const BasicCard = asBasicCard(Card);

In ths example, we could simply have provided our design directly as a prop:

const BasicCard: FC = () => <Card design={{

Wrapper: addClasses('font-sans'),

Title: addClasses('text-sm text-green'),

Body: addClasses('my-10'),

Cta: addClasses('block w-full bg-blue text-yellow py-1'),

}} />

However, by using withDesign() instead, our component itself will expose its own

design prop, allowing other consumers to further extend it:

const asPinkCard = withDesign({

Cta: addClasses('bg-pink').removeClasses('bg-blue'),

});

const PinkCard = asPinkCard(BasicCard);

In these examples, we are extending the default components. If we wanted

instead to replace one, we could write our HOC to ignore its argument

(or use the provided shortcut HOC replaceWith()):

const StylableH2 = stylable<JSX.IntrinsicElements['h2']>('h2');

const StandardH2 = addClasses('text-xl text-blue')(StylableH2);

const StandardCard = withDesign({

Title: replaceWith(StandardH2), // same as () => StandardH2

})(BasicCard);

We can also use the startWith() HOC, instead of replacing the whole component,

it will only replace the base component but still use any hoc that might have

wrapped it.

As with FClasses, HOC's created via withDesign() are themselves reusable, so

we can write:

const asStandardCard = withDesign({

Title: replaceWith(StandardH2), // same as () => StandardH2

});

const StandardCard = asStandardCard(Card);

const StandardPinkCard = asStandardCard(PinkCard);

const StandardRedCard = asStandardCard(RedCard);

And, also as with FClasses, the HOC's can be composed:

const StandardPinkAndGreenCard = flowRight(

withGreenCtaText,

asStandardCard,

asPinkCard,

)(BasicCard);

It is sometimes useful to apply classes conditionally, based on props passed to a component and/or some enclosing state. The FClasses design API includes some helper methods which make this easier.

Imagine we have a button which has different variants depending on whether it is

active and/or whether it is the first in a list of buttons. We can use the

addClassesIf(), removeClassesIf(), withoutProps() and hasProp() helpers

to accomplish this:

type VariantProps = {

isActive?: boolean,

isFirst?: boolean,

isEnabled?: boolean,

};

const Div = stylable<HTMLProps<HTMLDivElement>>('div');

const isActive = (props: any) => hasProp('isActive')(props);

const isFirst = (props: any) => hasProp('isFirst')(props);

const ContextMenuButton = flowHoc(

withoutProps<VariantProps>(['isActive', 'isFirst'),

addClasses('cursor-pointer pl-2 text-gray'),

addClassesIf(isActive)('text-white'),

removeClassesIf(isActive)('text-gray'),

removeClassesIf(isFirst)('pl-2'),

)(Div);

Note: Our innermost HOC is

withoutProps(). This guarantees that the props used to control styling won't be passed to thedivelement. We must explicitly type the genericwithoutProps(). This ensures that the type of the resulting component will include these props.

Imagine we have a button which consume some state from a react context. We can

use addClassesIf and removeClassesIf helpers to add classes to the button

conditionally:

const ToggleContext = React.createContext({

state: false,

toggleState: () => undefined,

});

const useIsToggled = () => React.useContext(ToggleContext).state;

const useToggle = () => React.useContext(ToggleContext).toggleState;

const ToggleContextProvider: FC = ({ children }) => {

const [state, setState] = React.useState(false);

const value = {

state,

toggleState: React.useCallback(() => setState(s => !s), []),

};

return (

<ToggleContext.Provider value={value}>

{children}

</ToggleContext.Provider>

);

};

const Toggle = ({ children, ...rest }) => <Button {...rest} onClick={useToggle()}>{children || 'Click Me'}</Button>;

const StyledToggle = addClassesIf(useIsToggled)('bg-emerald-200')(Toggle);

Here we pass a custom hook (useIsToggled) to addClassesIf. This hook consumes

the toggle state from the context, and applies the classes only if toggled on.

You can use the similar addPropsIf hoc to add props as well as styles to a

component conditioonally:

const StyledToggle = flowHoc(

addClassesIf(useIsToggled)('bg-emerald-200'),

addPropsIf(useIsToggled)({ children: 'On' }),

addPropsIf(() => !useIsToggled())({ children: 'Off' }),

);

A more general version of the above pattern is provided by th flowIf utility.

This takes a condition hoo (like addClassesIf) and returns a version of

flowHoc which applies only if the condition evaluates to true. The above

example could be rewritten using a flow toggle as:

const StyledToggle = flowHoc(

flowIf(useIsToggled)(

addClasses('bg-emerald-200'),

addProps({ children: 'On' }),

),

flowIf(() => !useIsToggled)(

addProps({ children: 'Off' }),

),

)(Toggle);

This is more powerful than addClassesIf since you can pass any collection of

tokens to the function returned by flowIf. For example, we could use it

to replace the component entirely:

const ReplacedToggle = flowIf(useIsToggled)(

replaceWith(SomeOtherComponent),

)(Toggle);

Note howeer that unlike addClassesIf and addPropsIf,

this will cause the enhanced component to be recreated (and

thus lose state) whenever the condition changes. For example, imagine

our base Toggle kept a counter:

const Toggle = ({ children, ...rest }) => {

const [count, setCount] = React.useState(1);

const toggle = useToggle();

const onClick = React.useCallback(() => {

setCount(c => c + 1);

toggle();

}, [toggle]);

return <Button {...rest} onClick={onClick}>Count is {count}</Button>;

}

Now compare

const StyledToggle = flowIf(useIsToggled)(addClasses('bg-emerald-200'))(Toggle);

with

const StyledToggle = addClassesIf(useIsToggled)('bg-emerald-200')(Toggle);

The first will lose the counter state every time the button is clicked, while the second will properly retain it.

For convenience, Bodiless packages often export a reusable flow toggle which

encapsulates its condition. One example is the ifEditable flow toggle

exported by @bodiless/core, which allows you to apply tokens only when

in edit mode.

One of the most powerful features of the Design API is the ability to create multiple variants of a component by composing different tokens onto it. These variants can then be fed to component selectors like the Flow Container or Chameleon) to provide a content editor with a range of options.

Such component selectors themselves accept a "fluid" or 'flexibe" design; that is, a design which can accept any number of arbitrary keys, rather than one with a fixed set of keys corresponding to fixed "slots" in the designable component. Each key in this flexible design represents one variant.

You can use th varyDesigns helper to simplify the process of creating a large

number of variants. varyDesigns accepts any number of designs, and produces a

new design created by composing the keys of each design with each key of the

other designs (essentially a matrix multiplication). It's easiest to explain

with an example:

import { varyDesigns } from '@bodiless/fclasses';

const base = {

Box: flowHoc(startWith(Div), asBox),

};

const borders = {

Rounded: asRounded,

Square: asSquare,

};

const bgColors = {

Orange: asOrange,

Blue: asBlue,

Teal: asTeal,

};

const variations = varyDesigns(

base,

borders,

bgColors,

);

Here we first define a base design, which contains the tokens to be shared among all variants. Then we create a separate design for each dimension of variation. Finally, we combine them to produce our set of variations, which in this case will be:

{

BoxRoundedOrange: flowHoc(startWith(Box), asBox, asRounded, asOrange),

BoxRoundedBlue: flowHoc(startWith(Box), asBox, asRounded, asBlue),

BoxRoundedRed: flowHoc(startWith(Box), asBox, asRounded, asRed),

BoxSquareOrange: flowHoc(startWith(Box), asBox, asRounded, asOrange),

BoxSquareBlue: flowHoc(startWith(Box), asBox, asRounded, asBlue),

BoxSquareRed: flowHoc(startWith(Box), asBox, asRounded, asRed),

}

In some cases, you may want to restrict the options. For example, if we introduce border color into the mix, we may not want to allow certain combinations of backgrounds and borders. This can be done by creating an intermediate design with the exact variations we want:

import pick from 'lodash/pick';

const borderColors = {

Blue: withBlueBorder,

Teal: withTealBorder,

};

const colors = {

...varyDesigns(

pick(bgColors, 'Orange'),

borderColors,

),

...varyDesigns(

pick(bgColors, 'Blue'),

pick(borderColors, 'Teal'),

),

...varyDesigns(

pick(bgColors, 'Teal'),

pick(borderColors, 'Blue'),

),

};

This will produce

{

OrangeBlue: flowHoc(asOrange, withBlueBorder),

OrangeTeal: flowHoc(asOrange, withTealBorder),

BlueTeal: flowHoc(asBlue, withTealBorder),

TealBlue: flowHoc(asTeal, withBlueBorder),

}

which can then be composed with our border styles to produce the final set of variations:

const variations = varyDesigns<any>(

base,

borders,

colors,

);

which produces

{

BoxRoundedOrangeBlue: flowHoc(startWith(Box), asBox, asRounded, asOrange, withBlueBackground),

BoxRoundedOrangeTeal: flowHoc(startWith(Box), asBox, asRounded, asOrange, withTealBackground),

BoxRoundedBlueTeal: flowHoc(startWith(Box), asBox, asRounded, asBlue, withTealBackground),

BoxRoundedTealBlue: flowHoc(startWith(Box), asBox, asRounded, asTeal, withBlueBackground),

BoxSquareOrangeBlue: flowHoc(startWith(Box), asBox, asSquare, asOrange, withBlueBackground),

BoxSquareOrangeTeal: flowHoc(startWith(Box), asBox, asSquare , asOrange, withTealBackground),

BoxSquareBlueTeal: flowHoc(startWith(Box), asBox, asSquare, asBlue, withTealBackground),

BoxSquareTealBlue: flowHoc(startWith(Box), asBox, asSquare, asTeal, withBlueBackground),

}

Note in all the above examples, the design keys produced by varyDesign are

constructed simply by concatenating the keys of all the keys which are composed

in each.

Note also that all the tokens composed above could themselves be designs which apply to on the base component which is being varied. For example, if instead of

const base = flowHoc(startWith(Div), asBox);

we had

const base = flowHoc(startWith(SomeDesignableComponentWithAWrapper), ...);

Then our individual style tokens might look like this:

const asOrange = withDesign({

Wrapper: addClasses('bg-orange'),

});

FAQs

Allows for the injection of functional class into components.

The npm package @bodiless/fclasses receives a total of 2 weekly downloads. As such, @bodiless/fclasses popularity was classified as not popular.

We found that @bodiless/fclasses demonstrated a not healthy version release cadence and project activity because the last version was released a year ago. It has 5 open source maintainers collaborating on the project.

Did you know?

Socket for GitHub automatically highlights issues in each pull request and monitors the health of all your open source dependencies. Discover the contents of your packages and block harmful activity before you install or update your dependencies.

Research

Security News

The Socket Research Team has discovered six new malicious npm packages linked to North Korea’s Lazarus Group, designed to steal credentials and deploy backdoors.

Security News

Socket CEO Feross Aboukhadijeh discusses the open web, open source security, and how Socket tackles software supply chain attacks on The Pair Program podcast.

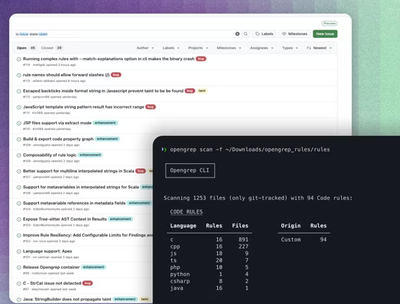

Security News

Opengrep continues building momentum with the alpha release of its Playground tool, demonstrating the project's rapid evolution just two months after its initial launch.