Security News

Crates.io Users Targeted by Phishing Emails

The Rust Security Response WG is warning of phishing emails from rustfoundation.dev targeting crates.io users.

@fp-ts/schema

Advanced tools

Modeling the schema of data structures as first-class values

Welcome to the documentation for @fp-ts/schema, a library for defining and using schemas to validate and transform data in TypeScript.

@fp-ts/schema allows you to define a Schema that describes the structure and data types of a piece of data, and then use that Schema to perform various operations such as decoding from unknown, encoding to unknown, verifying that a value conforms to a given Schema.

@fp-ts/schema also provides a number of other features, including the ability to derive various artifacts such as Arbitrarys, JSONSchemas, and Prettys from a Schema, as well as the ability to customize the library through the use of custom artifact compilers and custom Schema combinators.

If you're eager to learn how to define your first schema, jump straight to the Basic usage section!

This library was inspired by the following projects:

A huge thanks to my sponsors who made the development of @fp-ts/schema possible.

If you also want to become a sponsor to ensure this library continues to improve and receive maintenance, check out my GitHub Sponsors profile

strict flag enabled in your tsconfig.json fileexactOptionalPropertyTypes flag enabled in your tsconfig.json file{

// ...

"compilerOptions": {

// ...

"strict": true,

"exactOptionalPropertyTypes": true

}

}

To install the alpha version:

npm install @fp-ts/schema

Warning. This package is primarily published to receive early feedback and for contributors, during this development phase we cannot guarantee the stability of the APIs, consider each release to contain breaking changes.

Once you have installed the library, you can import the necessary types and functions from the @fp-ts/schema module.

import * as S from "@fp-ts/schema";

To define a Schema, you can use the provided struct function to define a new Schema that describes an object with a fixed set of properties. Each property of the object is described by a Schema, which specifies the data type and validation rules for that property.

For example, consider the following Schema that describes a person object with a name property of type string and an age property of type number:

import * as S from "@fp-ts/schema";

const Person = S.struct({

name: S.string,

age: S.number,

});

You can also use the union function to define a Schema that describes a value that can be one of a fixed set of types. For example, the following Schema describes a value that can be either a string or a number:

const StringOrNumber = S.union(S.string, S.number);

In addition to the provided struct and union functions, @fp-ts/schema also provides a number of other functions for defining Schemas, including functions for defining arrays, tuples, and records.

Once you have defined a Schema, you can use the Infer type to extract the inferred type of the data described by the Schema.

For example, given the Person Schema defined above, you can extract the inferred type of a Person object as follows:

interface Person extends S.Infer<typeof Person> {}

/*

interface Person {

readonly name: string;

readonly age: number;

}

*/

To use the Schema defined above to decode a value from unknown, you can use the decode function from the @fp-ts/schema/Parser module:

import * as S from "@fp-ts/schema";

const Person = S.struct({

name: S.string,

age: S.number,

});

const decodePerson = S.decode(Person);

const result1 = decodePerson({ name: "Alice", age: 30 });

if (S.isSuccess(result1)) {

console.log(result1.right); // { name: "Alice", age: 30 }

}

const result2 = decodePerson(null);

if (S.isFailure(result2)) {

console.log(result2.left); // [PR.type(..., null)]

}

The decodePerson function returns a value of type ParseResult<A>, which is a type alias for Either<NonEmptyReadonlyArray<ParseError>, A>, where NonEmptyReadonlyArray<ParseError> represents a list of errors that occurred during the decoding process and A is the inferred type of the data described by the Schema. A successful decode will result in a Right, containing the decoded data. A Right value indicates that the decode was successful and no errors occurred. In the case of a failed decode, the result will be a Left value containing a list of ParseErrors.

The decodeOrThrow function is used to decode a value and throw an error if the decoding fails.

It is useful when you want to ensure that the value being decoded is in the correct format, and want to throw an error if it is not.

try {

const person = P.decodeOrThrow(Person)({});

console.log(person);

} catch (e) {

console.error("Decoding failed:");

console.error(e);

}

/*

Decoding failed:

1 error(s) found

└─ key "name"

└─ is missing

*/

When using a Schema to decode a value, any properties that are not specified in the Schema will result in a decoding error. This is because the Schema is expecting a specific shape for the decoded value, and any excess properties do not conform to that shape.

However, you can use the isUnexpectedAllowed option to allow excess properties while decoding. This can be useful in cases where you want to be permissive in the shape of the decoded value, but still want to catch any potential errors or unexpected values.

Here's an example of how you might use isUnexpectedAllowed:

import * as S from "@fp-ts/schema";

const Person = S.struct({

name: S.string,

age: S.number,

});

console.log(

"%o",

S.decode(Person)(

{

name: "Bob",

age: 40,

email: "bob@example.com",

},

{ isUnexpectedAllowed: true }

)

);

/*

{

_tag: 'Right',

right: { name: 'Bob', age: 40 }

}

*/

The allErrors option is a feature that allows you to receive all decoding errors when attempting to decode a value using a schema. By default only the first error is returned, but by setting the allErrors option to true, you can receive all errors that occurred during the decoding process. This can be useful for debugging or for providing more comprehensive error messages to the user.

Here's an example of how you might use allErrors:

import * as S from "@fp-ts/schema";

const Person = S.struct({

name: S.string,

age: S.number,

});

console.log(

"%o",

S.decode(Person)(

{

name: "Bob",

age: "abc",

email: "bob@example.com",

},

{ allErrors: true }

)

);

/*

{

_tag: 'Left',

left: [

{

_tag: 'Key',

key: 'age',

errors: [

{ _tag: 'Type', expected: ..., actual: 'abc' },

[length]: 1

]

},

{

_tag: 'Key',

key: 'email',

errors: [

{ _tag: 'Unexpected', actual: 'bob@example.com' },

[length]: 1

]

},

[length]: 2

]

}

*/

To use the Schema defined above to encode a value to unknown, you can use the encode function:

import * as S from "@fp-ts/schema";

import { pipe } from "@effect/data/Function";

import { parseNumber } from "@fp-ts/schema/data/parser";

// Age is a schema that can decode a string to a number and encode a number to a string

const Age = pipe(S.string, parseNumber);

const Person = S.struct({

name: S.string,

age: Age,

});

const encoded = S.encode(Person)({ name: "Alice", age: 30 });

if (S.isSuccess(encoded)) {

console.log(encoded.right); // { name: "Alice", age: "30" }

}

Note that during encoding, the number value 30 was converted to a string "30".

To format errors when a decode or an encode function fails, you can use the format function from the @fp-ts/schema/formatter/Tree module.

import * as S from "@fp-ts/schema";

import { formatErrors } from "@fp-ts/schema/formatter/Tree";

const Person = S.struct({

name: S.string,

age: S.number,

});

const result = S.decode(Person)({});

if (S.isFailure(result)) {

console.error("Decoding failed:");

console.error(formatErrors(result.left));

}

/*

Decoding failed:

1 error(s) found

└─ key "name"

└─ is missing

*/

The is function provided by the @fp-ts/schema/Parser module represents a way of verifying that a value conforms to a given Schema. is is a refinement that takes a value of type unknown as an argument and returns a boolean indicating whether or not the value conforms to the Schema.

import * as S from "@fp-ts/schema";

const Person = S.struct({

name: S.string,

age: S.number,

});

// const isPerson: (u: unknown) => u is Person

const isPerson = S.is(Person);

console.log(isPerson({ name: "Alice", age: 30 })); // true

console.log(isPerson(null)); // false

console.log(isPerson({})); // false

The asserts function takes a Schema and returns a function that takes an input value and checks if it matches the schema. If it does not match the schema, it throws an error with a comprehensive error message.

import * as S from "@fp-ts/schema";

const Person = S.struct({

name: S.string,

age: S.number,

});

// const assertsPerson: (input: unknown) => asserts input is Person

const assertsPerson: S.InferAsserts<typeof Person> = P.asserts(Person);

try {

assertsPerson({ name: "Alice", age: "30" });

} catch (e) {

console.error("The input does not match the schema:");

console.error(e);

}

/*

The input does not match the schema:

Error: 1 error(s) found

└─ key "age"

└─ Expected number, actual "30"

*/

// this will not throw an error

assertsPerson({ name: "Alice", age: 30 });

The arbitrary function provided by the @fp-ts/schema/Arbitrary module represents a way of generating random values that conform to a given Schema. This can be useful for testing purposes, as it allows you to generate random test data that is guaranteed to be valid according to the Schema.

import * as S from "@fp-ts/schema";

import * as A from "@fp-ts/schema/Arbitrary";

import * as fc from "fast-check";

const Person = S.struct({

name: S.string,

age: S.number,

});

const PersonArbitrary = A.arbitrary(Person)(fc);

console.log(fc.sample(PersonArbitrary, 2));

/*

[

{ name: '!U?z/X', age: -2.5223372357846707e-44 },

{ name: 'valukeypro', age: -1.401298464324817e-45 }

]

*/

The pretty function provided by the @fp-ts/schema/Pretty module represents a way of pretty-printing values that conform to a given Schema.

You can use the pretty function to create a human-readable string representation of a value that conforms to a Schema. This can be useful for debugging or logging purposes, as it allows you to easily inspect the structure and data types of the value.

import * as S from "@fp-ts/schema";

import * as P from "@fp-ts/schema/Pretty";

const Person = S.struct({

name: S.string,

age: S.number,

});

const PersonPretty = P.pretty(Person);

// returns a string representation of the object

console.log(PersonPretty({ name: "Alice", age: 30 })); // `{ "name": "Alice", "age": 30 }`

import * as S from "@fp-ts/schema";

// primitive values

S.string;

S.number;

S.bigint;

S.boolean;

S.symbol;

S.object;

S.date; // value must be a Date

// empty types

S.undefined;

S.void; // accepts undefined

// catch-all types

// allows any value

S.any;

S.unknown;

// never type

// allows no values

S.never;

S.null; // same as S.literal(null)

S.literal("a");

S.literal("a", "b", "c"); // union of literals

S.literal(1);

S.literal(2n); // bigint literal

S.literal(true);

The templateLiteral combinator allows you to create a schema for a TypeScript template literal type.

// $ExpectType Schema<`a${string}`>

S.templateLiteral(S.literal("a"), S.string);

// example from https://www.typescriptlang.org/docs/handbook/2/template-literal-types.html

const EmailLocaleIDs = S.literal("welcome_email", "email_heading");

const FooterLocaleIDs = S.literal("footer_title", "footer_sendoff");

// $ExpectType Schema<"welcome_email_id" | "email_heading_id" | "footer_title_id" | "footer_sendoff_id">

S.templateLiteral(S.union(EmailLocaleIDs, FooterLocaleIDs), S.literal("_id"));

Note. Please note that the use of filters do not alter the type of the Schema. They only serve to add additional constraints to the decoding process.

pipe(S.string, S.maxLength(5));

pipe(S.string, S.minLength(5));

pipe(S.string, nonEmpty()); // same as S.minLength(1)

pipe(S.string, S.length(5));

pipe(S.string, S.pattern(regex));

pipe(S.string, S.startsWith(string));

pipe(S.string, S.endsWith(string));

pipe(S.string, S.includes(searchString));

pipe(S.string, S.trimmed()); // verifies that a string contains no leading or trailing whitespaces

Note: The trimmed combinator does not make any transformations, it only validates. If what you were looking for was a combinator to trim strings, then check out the trim combinator.

pipe(S.number, S.greaterThan(5));

pipe(S.number, S.greaterThanOrEqualTo(5));

pipe(S.number, S.lessThan(5));

pipe(S.number, S.lessThanOrEqualTo(5));

pipe(S.number, S.between(-2, 2)); // -2 <= x <= 2

pipe(S.number, S.int()); // value must be an integer

pipe(S.number, S.nonNaN()); // not NaN

pipe(S.number, S.finite()); // ensures that the value being decoded is finite and not equal to Infinity or -Infinity

pipe(S.number, S.positive()); // > 0

pipe(S.number, S.nonNegative()); // >= 0

pipe(S.number, S.negative()); // < 0

pipe(S.number, S.nonPositive()); // <= 0

import * as B from "@fp-ts/schema/data/Bigint";

pipe(S.bigint, B.greaterThan(5n));

pipe(S.bigint, B.greaterThanOrEqualTo(5n));

pipe(S.bigint, B.lessThan(5n));

pipe(S.bigint, B.lessThanOrEqualTo(5n));

pipe(S.bigint, B.between(-2n, 2n)); // -2n <= x <= 2n

pipe(S.bigint, B.positive()); // > 0n

pipe(S.bigint, B.nonNegative()); // >= 0n

pipe(S.bigint, B.negative()); // < 0n

pipe(S.bigint, B.nonPositive()); // <= 0n

pipe(S.array(S.number), A.maxItems(2)); // max array length

pipe(S.array(S.number), A.minItems(2)); // min array length

pipe(S.array(S.number), A.itemsCount(2)); // exact array length

enum Fruits {

Apple,

Banana,

}

// $ExpectType Schema<Fruits>

S.enums(Fruits);

// $ExpectType Schema<string | null>

S.nullable(S.string);

@fp-ts/schema includes a built-in union combinator for composing "OR" types.

// $ExpectType Schema<string | number>

S.union(S.string, S.number);

TypeScript reference: https://www.typescriptlang.org/docs/handbook/2/narrowing.html#discriminated-unions

Discriminated unions in TypeScript are a way of modeling complex data structures that may take on different forms based on a specific set of conditions or properties. They allow you to define a type that represents multiple related shapes, where each shape is uniquely identified by a shared discriminant property.

In a discriminated union, each variant of the union has a common property, called the discriminant. The discriminant is a literal type, which means it can only have a finite set of possible values. Based on the value of the discriminant property, TypeScript can infer which variant of the union is currently in use.

Here is an example of a discriminated union in TypeScript:

type Circle = {

readonly kind: "circle";

readonly radius: number;

};

type Square = {

readonly kind: "square";

readonly sideLength: number;

};

type Shape = Circle | Square;

This code defines a discriminated union using the @fp-ts/schema library:

import * as S from "@fp-ts/schema";

const Circle = S.struct({

kind: S.literal("circle"),

radius: S.number,

});

const Square = S.struct({

kind: S.literal("square"),

sideLength: S.number,

});

const Shape = S.union(Circle, Square);

The literal combinator is used to define the discriminant property with a specific string literal value.

Two structs are defined for Circle and Square, each with their own properties. These structs represent the variants of the union.

Finally, the union combinator is used to create a schema for the discriminated union Shape, which is a union of Circle and Square.

If you're working on a TypeScript project and you've defined a simple union to represent a particular input, you may find yourself in a situation where you're not entirely happy with how it's set up. For example, let's say you've defined a Shape union as a combination of Circle and Square without any special property:

import * as S from "@fp-ts/schema";

const Circle = S.struct({

radius: S.number,

});

const Square = S.struct({

sideLength: S.number,

});

const Shape = S.union(Circle, Square);

To make your code more manageable, you may want to transform the simple union into a discriminated union. This way, TypeScript will be able to automatically determine which member of the union you're working with based on the value of a specific property.

To achieve this, you can add a special property to each member of the union, which will allow TypeScript to know which type it's dealing with at runtime. Here's how you can transform the Shape schema into another schema that represents a discriminated union:

import * as S from "@fp-ts/schema";

import { pipe } from "@effect/data/Function";

const Circle = S.struct({

radius: S.number,

});

const Square = S.struct({

sideLength: S.number,

});

const DiscriminatedShape = S.union(

pipe(

Circle,

S.transform(

pipe(Circle, S.extend(S.struct({ kind: S.literal("circle") }))), // Add a "kind" property with the literal value "circle" to Circle

(circle) => ({ ...circle, kind: "circle" as const }), // Add the discriminant property to Circle

({ kind: _kind, ...rest }) => rest // Remove the discriminant property

)

),

pipe(

Square,

S.transform(

pipe(Square, S.extend(S.struct({ kind: S.literal("square") }))), // Add a "kind" property with the literal value "square" to Square

(square) => ({ ...square, kind: "square" as const }), // Add the discriminant property to Square

({ kind: _kind, ...rest }) => rest // Remove the discriminant property

)

)

);

expect(S.decodeOrThrow(DiscriminatedShape)({ radius: 10 })).toEqual({

kind: "circle",

radius: 10,

});

expect(S.decodeOrThrow(DiscriminatedShape)({ sideLength: 10 })).toEqual({

kind: "square",

sideLength: 10,

});

In this example, we use the extend function to add a "kind" property with a literal value to each member of the union. Then we use transform to add the discriminant property and remove it afterwards. Finally, we use union to combine the transformed schemas into a discriminated union.

However, when we use the schema to encode a value, we want the output to match the original input shape. Therefore, we must remove the discriminant property we added earlier from the encoded value to match the original shape of the input.

The previous solution works perfectly and shows how we can add and remove properties to our schema at will, making it easier to consume the result within our domain model. However, it requires a lot of boilerplate. Fortunately, there is an API called attachPropertySignature designed specifically for this use case, which allows us to achieve the same result with much less effort:

const Circle = S.struct({ radius: S.number });

const Square = S.struct({ sideLength: S.number });

const DiscriminatedShape = S.union(

pipe(Circle, S.attachPropertySignature("kind", "circle")),

pipe(Square, S.attachPropertySignature("kind", "square"))

);

// decoding

expect(S.decodeOrThrow(DiscriminatedShape)({ radius: 10 })).toEqual({

kind: "circle",

radius: 10,

});

// encoding

expect(

S.encodeOrThrow(DiscriminatedShape)({

kind: "circle",

radius: 10,

})

).toEqual({ radius: 10 });

// $ExpectType Schema<readonly [string, number]>

S.tuple(S.string, S.number);

// $ExpectType Schema<readonly [string, number, boolean]>

pipe(S.tuple(S.string, S.number), S.element(S.boolean));

// $ExpectType Schema<readonly [string, number, boolean?]>

pipe(S.tuple(S.string, S.number), S.optionalElement(S.boolean));

// $ExpectType Schema<readonly [string, number, ...boolean[]]>

pipe(S.tuple(S.string, S.number), S.rest(S.boolean));

// $ExpectType Schema<readonly number[]>

S.array(S.number);

// $ExpectType Schema<readonly [number, ...number[]]>

S.nonEmptyArray(S.number);

// $ExpectType Schema<{ readonly a: string; readonly b: number; }>

S.struct({ a: S.string, b: S.number });

// $ExpectType Schema<{ readonly a: string; readonly b: number; readonly c?: boolean; }>

S.struct({ a: S.string, b: S.number, c: S.optional(S.boolean) });

Note. The optional constructor only exists to be used in combination with the struct API to signal an optional field and does not have a broader meaning. This means that it is only allowed to use it as an outer wrapper of a Schema and it cannot be followed by other combinators, for example this type of operation is prohibited:

S.struct({

// the use of S.optional should be the last step in the pipeline and not preceeded by other combinators like S.nullable

c: pipe(S.boolean, S.optional, S.nullable), // type checker error

});

and it must be rewritten like this:

S.struct({

c: pipe(S.boolean, S.nullable, S.optional), // ok

});

The getPropertySignatures function takes a Schema<A> and returns a new object of type { [K in keyof A]: Schema<A[K]> }. The new object has properties that are the same keys as those in the original object, and each of these properties is a schema for the corresponding property in the original object.

import * as S from "@fp-ts/schema";

const Person = S.struct({

name: S.string,

age: S.number,

});

// get the schema for each property of `Person`

const shape = S.getPropertySignatures(Person);

shape.name; // S.string

shape.age; // S.number

// $ExpectType Schema<{ readonly a: string; }>

pipe(S.struct({ a: S.string, b: S.number }), S.pick("a"));

// $ExpectType Schema<{ readonly b: number; }>

pipe(S.struct({ a: S.string, b: S.number }), S.omit("a"));

// $ExpectType Schema<Partial<{ readonly a: string; readonly b: number; }>>

S.partial(S.struct({ a: S.string, b: S.number }));

// $ExpectType Schema<{ readonly [x: string]: string; }>

S.record(S.string, S.string);

// $ExpectType Schema<{ readonly a: string; readonly b: string; }>

S.record(S.union(S.literal("a"), S.literal("b")), S.string);

// $ExpectType Schema<{ readonly [x: string]: string; }>

S.record(pipe(S.string, S.minLength(2)), S.string);

// $ExpectType Schema<{ readonly [x: symbol]: string; }>

S.record(S.symbol, S.string);

// $ExpectType Schema<{ readonly [x: `a${string}`]: string; }>

S.record(S.templateLiteral(S.literal("a"), S.string), S.string);

The extend combinator allows you to add additional fields or index signatures to an existing Schema.

// $ExpectType Schema<{ [x: string]: string; readonly a: string; readonly b: string; readonly c: string; }>

pipe(

S.struct({ a: S.string, b: S.string }),

S.extend(S.struct({ c: S.string })), // <= you can add more fields

S.extend(S.record(S.string, S.string)) // <= you can add index signatures

);

In the following section, we demonstrate how to use the instanceOf combinator to create a Schema for a class instance.

class Test {

constructor(readonly name: string) {}

}

// $ExpectType Schema<Test>

pipe(S.object, S.instanceOf(Test));

The lazy combinator is useful when you need to define a Schema that depends on itself, like in the case of recursive data structures. In this example, the Category schema depends on itself because it has a field subcategories that is an array of Category objects.

interface Category {

readonly name: string;

readonly subcategories: ReadonlyArray<Category>;

}

const Category: S.Schema<Category> = S.lazy(() =>

S.struct({

name: S.string,

subcategories: S.array(Category),

})

);

Here's an example of two mutually recursive schemas, Expression and Operation, that represent a simple arithmetic expression tree.

interface Expression {

readonly type: "expression";

readonly value: number | Operation;

}

interface Operation {

readonly type: "operation";

readonly operator: "+" | "-";

readonly left: Expression;

readonly right: Expression;

}

const Expression: S.Schema<Expression> = S.lazy(() =>

S.struct({

type: S.literal("expression"),

value: S.union(S.number, Operation),

})

);

const Operation: S.Schema<Operation> = S.lazy(() =>

S.struct({

type: S.literal("operation"),

operator: S.union(S.literal("+"), S.literal("-")),

left: Expression,

right: Expression,

})

);

In some cases, we may need to transform the output of a schema to a different type. For instance, we may want to parse a string into a number, or we may want to transform a date string into a Date object.

To perform these kinds of transformations, the @fp-ts/schema library provides the transform and transformOrFail combinators.

The transform combinator takes a target schema, a transformation function from the source type to the target type, and a reverse transformation function from the target type back to the source type. It returns a new schema that applies the transformation function to the output of the original schema before returning it. If the original schema fails to decode a value, the transformed schema will also fail.

import * as S from "@fp-ts/schema";

// define a schema for the string type

const stringSchema: S.Schema<string> = S.string;

// define a schema for a tuple with one element of type string

const tupleSchema: S.Schema<[string]> = S.tuple(S.string);

// define a function that converts a string into a tuple with one element of type string

const decode = (s: string): [string] => [s];

// define a function that converts a tuple with one element of type string into a string

const encode = ([s]: [string]): string => s;

// use the transform combinator to convert the string schema into the tuple schema

const transformedSchema: S.Schema<[string]> = pipe(

stringSchema,

S.transform(tupleSchema, decode, encode)

);

In the example above, we defined a schema for the string type and a schema for the tuple type [string]. We also defined the functions decode and encode that convert a string into a tuple and a tuple into a string, respectively. Then, we used the transform combinator to convert the string schema into a schema for the tuple type [string]. The resulting schema can be used to decode values of type string into values of type [string].

The transformOrFail combinator works in a similar way, but allows the transformation function to return a ParseResult object, which can either be a success or a failure.

Here's an example of the transformOrFail combinator which converts a string into a boolean:

import { pipe } from "@effect/data/Function";

import * as PR from "@fp-ts/schema/ParseResult";

import * as S from "@fp-ts/schema";

import * as AST from "@fp-ts/schema/AST";

// define a schema for the string type

const stringSchema: S.Schema<string> = S.string;

// define a schema for the boolean type

const booleanSchema: S.Schema<boolean> = S.boolean;

// define a function that converts a string into a boolean

const decode = (s: string): PR.ParseResult<boolean> =>

s === "true"

? PR.success(true)

: s === "false"

? PR.success(false)

: PR.failure(

PR.type(AST.union([AST.literal("true"), AST.literal("false")]), s)

);

// define a function that converts a boolean into a string

const encode = (b: boolean): ParseResult<string> => PR.success(String(b));

// use the transformOrFail combinator to convert the string schema into the boolean schema

const transformedSchema: S.Schema<boolean> = pipe(

stringSchema,

S.transformOrFail(booleanSchema, decode, encode)

);

Transforms a string into a number by parsing the string using parseFloat.

The following special string values are supported: "NaN", "Infinity", "-Infinity".

import * as S from "@fp-ts/schema";

import { parseNumber } from "@fp-ts/schema/data/parser";

const schema = parseNumber(S.string);

const decodeOrThrow = S.decodeOrThrow(schema);

// success cases

decodeOrThrow("1"); // 1

decodeOrThrow("-1"); // -1

decodeOrThrow("1.5"); // 1.5

decodeOrThrow("NaN"); // NaN

decodeOrThrow("Infinity"); // Infinity

decodeOrThrow("-Infinity"); // -Infinity

// failure cases

decodeOrThrow("a"); // throws

The trim parser allows removing whitespaces from the beginning and end of a string.

import * as S from "@fp-ts/schema";

const schema = S.trim(S.string);

const decodeOrThrow = S.decodeOrThrow(schema);

decodeOrThrow("a"); // "a"

decodeOrThrow(" a"); // "a"

decodeOrThrow("a "); // "a"

decodeOrThrow(" a "); // "a"

Note. If you were looking for a combinator to check if a string is trimmed, check out the trimmed combinator.

Transforms a string into a Date by parsing the string using Date.parse.

import * as S from "@fp-ts/schema";

import { parseDate } from "@fp-ts/schema/data/parser";

const schema = parseDate(S.string);

const decodeOrThrow = S.decodeOrThrow(schema);

decodeOrThrow("1970-01-01T00:00:00.000Z"); // new Date(0)

decodeOrThrow("a"); // throws

The option combinator allows you to specify that a field in a schema may be either an optional value or null. This is useful when working with JSON data that may contain null values for optional fields.

In the example below, we define a schema for an object with a required a field of type string and an optional b field of type number. We use the option combinator to specify that the b field may be either a number or null.

import * as S from "@fp-ts/schema";

import * as O from "@effect/data/Option";

const schema = S.struct({

a: S.string,

// define a schema for Option with number values

b: S.option(S.number),

});

const decodeOrThrow = S.decodeOrThrow(schema);

decodeOrThrow({ a: "hello", b: null }); // { a: "hello", b: O.none }

decodeOrThrow({ a: "hello", b: 1 }); // { a: "hello", b: O.some(1) }

In the following section, we demonstrate how to use the fromValues combinator to decode a ReadonlySet from an array of values.

import * as S from "@fp-ts/schema";

import { fromValues } from "@fp-ts/schema/data/ReadonlySet";

// define a schema for ReadonlySet with number values

const schema = fromValues(S.number);

const decodeOrThrow = P.decodeOrThrow(schema);

decodeOrThrow([1, 2, 3]); // new Set([1, 2, 3])

In the following section, we demonstrate how to use the fromEntries combinator to decode a ReadonlyMap from an array of entries.

import * as S from "@fp-ts/schema";

import { fromEntries } from "@fp-ts/schema/data/ReadonlyMap";

// define the schema for ReadonlyMap with number keys and string values

const schema = fromEntries(S.number, S.string);

const decodeOrThrow = P.decodeOrThrow(schema);

decodeOrThrow([

[1, "a"],

[2, "b"],

[3, "c"],

]); // new Map([[1, "a"], [2, "b"], [3, "c"]])

The easiest way to define a new data type is through the filter combinator.

import * as S from "@fp-ts/schema";

const LongString = pipe(

S.string,

S.filter((s) => s.length >= 10, {

message: () => "a string at least 10 characters long",

})

);

console.log(S.decodeOrThrow(LongString)("a"));

/*

1 error(s) found

└─ Expected a string at least 10 characters long, actual "a"

*/

It is good practice to add as much metadata as possible so that it can be used later by introspecting the schema.

const LongString = pipe(

S.string,

S.filter((s) => s.length >= 10, {

message: () => "a string at least 10 characters long",

identifier: "LongString",

jsonSchema: { minLength: 10 },

description:

"Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua",

})

);

A schema is a description of a data structure that can be used to generate various artifacts from a single declaration.

From a technical point of view a schema is just a typed wrapper of an AST value:

interface Schema<in out A> {

readonly ast: AST;

}

The AST type represents a tiny portion of the TypeScript AST, roughly speaking the part describing ADTs (algebraic data types),

i.e. products (like structs and tuples) and unions.

This means that you can define your own schema constructors / combinators as long as you are able to manipulate the AST value accordingly, let's see an example.

Say we want to define a pair schema constructor, which takes a Schema<A> as input and returns a Schema<readonly [A, A]> as output.

First of all we need to define the signature of pair

import * as S from "@fp-ts/schema";

declare const pair: <A>(schema: S.Schema<A>) => S.Schema<readonly [A, A]>;

Then we can implement the body using the APIs exported by the @fp-ts/schema/AST module:

import * as S from "@fp-ts/schema";

import * as AST from "@fp-ts/schema/AST";

import * as O from "@effect/data/Option";

const pair = <A>(schema: S.Schema<A>): S.Schema<readonly [A, A]> => {

const element = AST.createElement(

schema.ast, // <= the element type

false // <= is optional?

);

const tuple = AST.createTuple(

[element, element], // <= elements definitions

O.none, // <= rest element

true // <= is readonly?

);

return S.make(tuple); // <= wrap the AST value in a Schema

};

This example demonstrates the use of the low-level APIs of the AST module, however, the same result can be achieved more easily and conveniently by using the high-level APIs provided by the Schema module.

const pair = <A>(schema: S.Schema<A>): S.Schema<readonly [A, A]> =>

S.tuple(schema, schema);

Please note that the S.tuple API is a convenient utility provided by the library, but it can also be easily defined and implemented in userland.

export const tuple = <Elements extends ReadonlyArray<Schema<any>>>(

...elements: Elements

): Schema<{ readonly [K in keyof Elements]: Infer<Elements[K]> }> =>

makeSchema(

AST.createTuple(

elements.map((schema) => AST.createElement(schema.ast, false)),

O.none,

true

)

);

One of the fundamental requirements in the design of @fp-ts/schema is that it is extensible and customizable. Customizations are achieved through "annotations". Each node contained in the AST of @fp-ts/schema/AST contains an annotations: Record<string | symbol, unknown> field that can be used to attach additional information to the schema.

Let's see some examples:

import { pipe } from "@effect/data/Function";

import * as S from "@fp-ts/schema";

const Password = pipe(

// initial schema, a string

S.string,

// add an error message for non-string values (annotation)

S.message(() => "not a string"),

// add a constraint to the schema, only non-empty strings are valid

S.nonEmpty,

// add an error message for empty strings (annotation)

S.message(() => "required"),

// add a constraint to the schema, only strings with a length less or equal than 10 are valid

S.maxLength(10),

// add an error message for strings that are too long (annotation)

S.message((s) => `${s} is too long`),

// add an identifier to the schema (annotation)

S.identifier("Password"),

// add a title to the schema (annotation)

S.title("password"),

// add a description to the schema (annotation)

S.description(

"A password is a string of characters used to verify the identity of a user during the authentication process"

),

// add examples to the schema (annotation)

S.examples(["1Ki77y", "jelly22fi$h"]),

// add documentation to the schema (annotation)

S.documentation(`

jsDoc documentation...

`)

);

The example shows some built-in combinators to add meta information, but users can easily add their own meta information by defining a custom combinator.

Here's an example of how to add a deprecated annotation:

import * as S from "@fp-ts/schema";

import * as AST from "@fp-ts/schema/AST";

import { pipe } from "@effect/data/Function";

const DeprecatedId = "some/unique/identifier/for/the/custom/annotation";

const deprecated = <A>(self: S.Schema<A>): S.Schema<A> =>

S.make(AST.annotation(self.ast, DeprecatedId, true));

const schema = pipe(S.string, deprecated);

console.log(schema);

/*

{

ast: {

_tag: 'StringKeyword',

annotations: {

'@fp-ts/schema/annotation/TitleId': 'string',

'some/unique/identifier/for/the/custom/annotation': true

}

}

}

*/

Annotations can be read using the getAnnotation helper, here's an example:

import * as O from "@effect/data/Option";

const isDeprecated = <A>(schema: S.Schema<A>): boolean =>

pipe(

AST.getAnnotation<boolean>(DeprecatedId)(schema.ast),

O.getOrElse(() => false)

);

console.log(isDeprecated(S.string)); // false

console.log(isDeprecated(schema)); // true

The MIT License (MIT)

FAQs

Unknown package

We found that @fp-ts/schema demonstrated a not healthy version release cadence and project activity because the last version was released a year ago. It has 3 open source maintainers collaborating on the project.

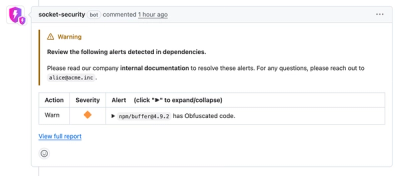

Did you know?

Socket for GitHub automatically highlights issues in each pull request and monitors the health of all your open source dependencies. Discover the contents of your packages and block harmful activity before you install or update your dependencies.

Security News

The Rust Security Response WG is warning of phishing emails from rustfoundation.dev targeting crates.io users.

Product

Socket now lets you customize pull request alert headers, helping security teams share clear guidance right in PRs to speed reviews and reduce back-and-forth.

Product

Socket's Rust support is moving to Beta: all users can scan Cargo projects and generate SBOMs, including Cargo.toml-only crates, with Rust-aware supply chain checks.