Research

/Security News

Critical Vulnerability in NestJS Devtools: Localhost RCE via Sandbox Escape

A flawed sandbox in @nestjs/devtools-integration lets attackers run code on your machine via CSRF, leading to full Remote Code Execution (RCE).

django-local-settings

Advanced tools

Define Django settings in config files and/or via environment variables

.env file and

they'll be loaded automatically, or any standard method of setting

environment variables can be used2021-06-23, etc)int

or float)This package attempts to solve the problem of handling local settings in Django projects. Local settings by definition can't be pre-defined, although perhaps they can have a reasonable default value (mainly useful for development). Another class of local settings are secret settings; these definitely shouldn't be pre-defined and should never be added to version control.

The problems with local settings are:

One common approach is to create a local settings template module with

dummy/default values. When new developers start working on a project,

they copy this file (e.g., local_settings.py.template => local_settings.py), which is typically excluded from version control.

This approach at least identifies which settings are local, but it's not

very convenient with regard to setting values and ensuring those values

are valid. Also, instead of giving you a friendly heads-up when you

forget to set a local setting, it barfs out an exception.

This package takes the approach that there will be only one settings

module* per project in the standard location: {project}.settings. That

module defines/overrides Django's base settings in the usual way plus

it defines which settings are local and which are secret.

In addition to the settings module, there will be one or more settings files. These are standard INI files with the added twist that the values are JSON encoded. The reasoning behind this is to use a simple, standard config file format while still allowing for easy handling of non-string settings.

In addition, interpolation is supported using Django-style {{ ... }}

syntax. This can be handy to avoid repetition.

Once the local settings are defined, any missing settings will be prompted for in the console (with pretty colors and readline support).

In addition to settings files, settings can defined via environment

variables. These can be defined in a .env file or using any other

mechanism for setting environment variables. When using a .env file,

the values will be read in automatically; when not using a .env

file, the corresponding environment variables will need to be set prior

to loading the local settings.

Env settings are typically strings like passwords and API tokens, but they will proccessed like other settings--values will be loaded as JSON and interpolated, etc.

.env file automatically, if presentconfigparser)In your project's settings module, import the inject_settings

function along with the types of settings you need:

from local_settings import (

inject_settings,

LocalSetting,

SecretSetting,

)

Then define some base settings and local settings:

# project/settings.py

from django.core.management import utils

# This is used to demonstrate interpolation.

PACKAGE = "local_settings"

DEBUG = LocalSetting(default=False)

# This setting will be loaded from the environment variable

# API_TOKEN, which can be defined in a .env file or set directly

# in the environment.

SOME_SERVICE = {

"api_token": EnvSetting("API_TOKEN"),

}

DATABASES = {

"default": {

"ENGINE": "django.db.backends.postgresql",

"NAME": LocalSetting(default="{{ PACKAGE }}"),

"USER": LocalSetting(""),

"PASSWORD": SecretSetting(),

"HOST": LocalSetting(""),

"PORT": "",

},

}

# If a secret setting specifies a default, it must be a callable

# that generates the value; this discourages using the same

# secret in different environments.

SECRET_KEY = SecretSetting(

default=utils.get_random_secret_key,

doc="The secret key for doing secret stuff",

)

Local settings can be nested inside other settings. They can also have doc strings, which are displayed when prompting, and default values or value generators, which are used as suggestions when prompting.

This also demonstrates interpolation. The DATABASES.default.NAME

setting will be replaced with the PACKAGE setting, so that its

default value is effectively 'top_level_package'.

After all the local settings are defined, add the following line:

inject_settings()

This initializes the local settings loader with the base settings from the settings module and tells it which settings are local settings. It then merges in the settings from the settings file.

inject_settings() loads the project's local settings from a file

($CWD/local.cfg by default), prompting for any that are missing,

and/or environment variables, and returns a new dictionary with

local settings merged over any base settings. When not running on

a TTY/console, missing local settings will cause an exception to be

raised.

After inject_settings() runs, you'll be able to access the local

settings in the settings module as usual, in case some dynamic

configuration is required. For example, you could do if DEBUG: .... At this point, DEBUG is no longer a LocalSetting

instance--it's a regular Python bool.

Now you can run any manage.py command, and you will be prompted to

enter any missing local settings. On the first run, the settings file

will be created. On subsequent runs when new local settings are added

to the settings module, the settings file will be appended to.

Alternatively, you can run the included make-local-settings script

to generate a local settings file.

TODO: Discuss using multiple settings files, extending a settings file

from another file, how to specify a settings file other than the default

of local.cfg, editing settings files directly, &c.

The initial commit of this package was made on October 22, 2014, and the first release was published to PyPI on March 11, 2015. At the time, I didn't know about TOML. Otherwise, I probably (maybe?) would have found a way to use TOML for Django settings.

When I heard about TOML--I think related to pyproject.toml becoming

a thing--I remember thinking it was quite similar to this package (or

vice versa), especially the splitting of dotted names into dictionaries

and the use of "rich" values rather than plain text.

One of the biggest differences, besides this package being Django- specific, is interpolation of both values and keys, which I find immensely useful (more for values, but occasionally for keys.)

Another difference is that with TOML the config file section name

becomes part of the dictionary structure, whereas in

django-local-settings it doesn't. In that regard,

django-local-settings is geared toward environments, such as

a development and production.

One other difference is that django-local-settings supports loading

settings from environment variables out of the box.

FAQs

Define Django settings in config files and/or via environment variables

We found that django-local-settings demonstrated a healthy version release cadence and project activity because the last version was released less than a year ago. It has 1 open source maintainer collaborating on the project.

Did you know?

Socket for GitHub automatically highlights issues in each pull request and monitors the health of all your open source dependencies. Discover the contents of your packages and block harmful activity before you install or update your dependencies.

Research

/Security News

A flawed sandbox in @nestjs/devtools-integration lets attackers run code on your machine via CSRF, leading to full Remote Code Execution (RCE).

Product

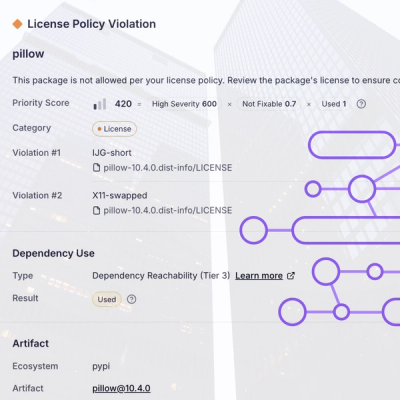

Customize license detection with Socket’s new license overlays: gain control, reduce noise, and handle edge cases with precision.

Product

Socket now supports Rust and Cargo, offering package search for all users and experimental SBOM generation for enterprise projects.