Security News

/Research

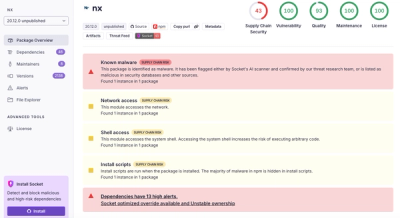

Wallet-Draining npm Package Impersonates Nodemailer to Hijack Crypto Transactions

Malicious npm package impersonates Nodemailer and drains wallets by hijacking crypto transactions across multiple blockchains.

apostrophe-schemas

Advanced tools

This module is for Apostrophe 0.5.x only. In Apostrophe 2.x, schemas are standard equipment.

Table of Contents

apostrophe-schemas adds support for simple schemas of editable properties to any object. Schema types include text, select, apostrophe areas and singletons, joins (relationships to other objects), and more. This module is used by the apostrophe-snippets module to implement its edit views and can also be used elsewhere.

In any project built with the apostrophe-site module, every module you configure in app.js will receive a schemas option, which is a ready-to-rock instance of the apostrophe-schemas module. You might want to add it as a property in your constructor:

self._schemas = options.schemas;

If you are not using apostrophe-site... well, you should be. But a reasonable alternative is to configure apostrophe-schemas yourself in app.js:

var schemas = require('apostrophe-schemas')({ app: app, apos: apos });

schemas.setPages(pages); // pages module must be injected

And then pass it as the schemas option to every module that will use it. But this is silly. Use apostrophe-site.

A schema is a simple array of objects specifying information about each field. The apostrophe-schemas module provides methods to build schemas, validate submitted data according to a schema, and carry out joins according to a schema. The module also provides browser-side JavaScript and Nunjucks templates to edit an object based on its schema.

Schema objects have intentionally been kept simple so that they can be send to the browser as JSON and interpreted by browser-side JavaScript as well.

The simplest way to create a schema is to just make an array yourself:

var schema = [

{

name: 'workPhone',

type: 'string',

label: 'Work Phone'

},

{

name: 'workFax',

type: 'string',

label: 'Work Fax'

},

{

name: 'department',

type: 'string',

label: 'Department'

},

{

name: 'isRetired',

type: 'boolean',

label: 'Is Retired'

},

{

name: 'isGraduate',

type: 'boolean',

label: 'Is Graduate'

},

{

name: 'classOf',

type: 'string',

label: 'Class Of'

},

{

name: 'location',

type: 'string',

label: 'Location'

}

]

});

However, if you are implementing a subclass and need to make changes to the schema of the superclass it'll be easier for you if the superclass uses the schemas.compose method, as described later.

Currently:

string, boolean, integer, float, select, url, date, time, slug, tags, password, area, singleton

Except for area, all of these types accept a def option which provides a default value if the field's value is not specified.

The integer and float types also accept min and max options and automatically clamp values to stay in that range.

The select type accepts a choices option which should contain an array of objects with value and label properties. In addition to value and label, each choice option can include a showFields option, which can be used to toggle visibility of other fields when being edited.

The date type pops up a jQuery UI datepicker when clicked on, and the time type tolerates many different ways of entering the time, like "1pm" or "1:00pm" and "13:00". For date, you can specify select: true to display dropdowns for year, month and day rather than a calendar control. When doing so you can also specify yearsFrom and yearsTo to give a range for the "year" dropdown. if these values are less than 1000 they are relative to the current year. You may even use an absolute year for yearsFrom and a relative year for yearsTo.

The url field type is tolerant of mistakes like leaving off http:.

The password field type stores a salted hash of the password via apos.hashPassword which can be checked later with the password-hash module. If the user enters nothing the existing password is not updated.

The tags option accepts a limit property which can be used to restrict the number of tags that can be added.

When using the area and singleton types, you may include an options property which will be passed to that area or singleton exactly as if you were passing it to aposArea or aposSingleton.

When using the singleton type, you must always specify widgetType to indicate what type of widget should appear.

Joins and arrays are also supported as described later.

For the most part, we favor sanitization over validation. It's better to figure out what the user meant on the server side than to give them a hard time. But sometimes validation is unavoidable.

You can make any field mandatory by giving it the required: true attribute. Currently this is only implemented in browser-side JavaScript, so your server-side code should be prepared not to crash if a property is unexpectedly empty.

If the user attempts to save without completing a required field, the apos-error class will be set on the fieldset element for that field, and schemas.convertFields will pass an error to its callback. If schemas.convertFields passes an error, your code should not attempt to save the object or close the dialog in question, but rather let the user continue to edit until the callback is invoked with no error.

If schemas.convertFields does pass an error, you may invoke:

aposSchemas.scrollToError($el)

To ensure that the first error in the form is visible.

If you are performing your own custom validation, you can call:

aposSchemas.addError($el, 'body')

To indicate that the field named body has an error, in the same style that is applied to errors detected via the schema.

One lonnnnng scrolling list of fields is usually not user-friendly.

You may group fields together into tabs instead using the groupFields option. Here's how you would do it if you wanted to override our tab choices for the blog:

modules: {

'apostrophe-blog': {

groupFields: [

// We don't list the title field so it stays on top

{

name: 'content',

label: 'Content',

icon: 'content',

fields: [

'thumbnail', 'body'

]

},

{

name: 'details',

label: 'Details',

icon: 'metadata',

fields: [

'slug', 'published', 'publicationDate', 'publicationTime', 'tags'

]

}

]

}

}

Each group has a name, a label, an icon (passed as a CSS class on the tab's icon element), and an array of field names.

In app.js, you can simply pass groupFields like any other option when configuring a module. The last call to groupFields wins, overriding any previous attempts to group the fields, so be sure to list all of them except for fields you want to stay visible at all times above the tabs.

Be aware that group names must be distinct from field names. Apostrophe will stop the music and tell you if they are not.

Let's say you're managing "companies," and each company has several "offices." Wouldn't it be nice if you could edit a list of offices while editing the company?

This is easy to do with the array field type:

{

name: 'offices',

label: 'Offices',

type: 'array',

minimize: true,

schema: [

{

name: 'city',

label: 'City',

type: 'string'

},

{

name: 'zip',

label: 'Zip',

type: 'string',

def: '19147'

},

{

name: 'thumbnail',

label: 'Thumbnail',

type: 'singleton',

widgetType: 'slideshow',

options: {

limit: 1

}

}

]

}

Each array has its own schema, which supports all of the usual field types. You an even nest an array in another array.

The minimize option of the array field type enables editors to expand or hide fields of an array in order to more easily work with longer lists of items or items with very long schemas.

It's easy to access the resulting information in a page template, such as the show template for companies. The array property is... you guessed it... an array! Not hard to iterate over at all:

<h4>Offices</h4>

<ul>

{% for office in item.offices %}

<li>{{ office.city }}, {{ office.zip }}</li>

{% endfor %}

</ul>

Areas and thumbnails are allowed in arrays. In order to display them in a page template, you'll need to use this syntax:

{% for office in item.offices %}

{{ aposSingleton({ area: office.thumbnail, type: 'slideshow', more options... }) }}

{% endfor %}

For an area you would write:

{% for office in item.offices %}

{{ aposArea({ area: office.body, more options... }) }}

{% endfor %}

Since the area is not a direct property of the page, we can't use the (page, areaname) syntax that is typically more convenient.

Areas and thumbnails in arrays can be edited "in context" on a page.

For most field types, you may specify:

autocomplete: false

To request that the browser not try to autocomplete the field's value for the user. The only fields that do not support this are those that are not implemented by a traditional HTML form field, and in all probability browsers won't autocomplete these anyway.

This is really easy! Just write this in your nunjucks template:

{% include 'schemas:schemaMacros.html' %}

<form class="my-form">

{{ schemaFields(schema) }}

</form>

Of course you must pass your schema to Nunjucks when rendering your template.

All of the fields will be presented with their standard markup, ready to be populated by aposSchemas.populateFields in browser-side JavaScript.

You may want to customize the way a particular field is output. The most future-proof way to do this is to use the custom option and pass your own macro:

{% macro renderTitle(field) %}

<fieldset data-name="{{ field.name }}" class="super-awesome">

special awesome title: <input name="{{ field.name }}" />

</fieldset>

{% endmacro %}

<form>

{{

schemaFields(schema, {

custom: {

title: renderTitle

}

})

}}

</form>

This way, Apostrophe outputs all of the fields for you, grouped into the proper tabs if any, but you still get to use your own macro to render this particular field.

If you want to include the standard rendering of a field as part of your custom output, use the aposSchemaField helper function:

aposSchemaField(field)

This will decorate the field with a fieldset in the usual way.

Note that the user's current values for the fields, if any, are added by browser-side JavaScript. You are not responsible for that in your template.

You also need to push your schema from the server so that it is visible to browser-side Javascript:

self._apos.pushGlobalData({

mymodule: {

schema: self.schema

}

});

Now you're ready to use the browser-side JavaScript to power up the editor. Note that the populateFields method takes a callback:

var schema = apos.data.mymodule.schema;

aposSchemas.populateFields($el, schema, object, function() {

// We're ready

});

$el should be a jQuery object referring to the element that contains all of the fields you output with schemaFields. object is an existing object containing existing values for some or all of the properties.

And, when you're ready to save the content:

aposSchemas.convertFields($el, schema, object)

This is the same in reverse. The properties of the object are set based on the values in the editor. Aggressive sanitization is not performed in the browser because the server must always do it anyway (never trust a browser). You may of course do your own validation after calling convertFields and perhaps decide the user is not done editing yet after all.

Serializing the object and sending it to the server is up to you. (We recommend using $.jsonCall.) But once it gets there, you can use the convertFields method to clean up the data and make sure it obeys the schema. The incoming fields should be properties of data, and will be sanitized and copied to properties of object. Then the callback is invoked:

schemas.convertFields(req, schema, 'form', data, object, callback)

The third argument is set to 'form' to indicate that this data came from a form and should go through that converter.

Now you can save object as you normally would.

For snippets, the entire object is usually edited in a modal dialog. But if you are using schemas to enhance regular pages via the apostrophe-fancy-pages module, you might prefer to edit certain areas and singletons "in context" on the page itself.

You could just leave them out of the schema, and take advantage of Apostrophe's support for "spontaneous areas" created by aposArea and aposSingleton calls in templates.

An alternative is to set contextual to true for such fields. This will keep them out of forms generated by {{ schemaFields }}, but will not prevent you from taking advantage of other features of schemas, such as CSV import.

Either way, it is your responsibility to add an appropriate aposArea or aposSingleton call to the page, as you are most likely doing already.

You may use the join type to automatically pull in related objects from this or another module. Typical examples include fetching events at a map location, or people in a group. This is very cool.

"Aren't joins bad? I read that joins were bad in some NoSQL article."

Short answer: no.

Long answer: sometimes. Mostly in so-called "webscale" projects, which have nothing to do with 99% of websites. If you are building the next Facebook you probably know that, and you'll denormalize your data instead and deal with all the fascinating bugs that come with maintaining two copies of everything.

Of course you have to be smart about how you use joins, and we've included options that help with that.

You might write this:

addFields: [

{

name: '_location',

type: 'joinByOne',

withType: 'mapLocation',

idField: 'locationId',

label: 'Location'

}

]

}

(How does this work? apostrophe-schemas will consult the apostrophe-pages module to find the manager object responsible for mapLocation objects, which will turn out to be the apostrophe-map module.)

Now the user can pick a map location. And if you call schema.join(req, schema, myObjectOrArrayOfObjects, callback), apostrophe-schemas will carry out the join, fetch the related object and populate the _location property of your object. Note that it is much more efficient to pass an array of objects if you need related objects for more than one.

Here's an example of using the resulting ._location property in a Nunjucks template:

{% if item._location %}

<a href="{{ item._location.url | e }}">Location: {{ item._location.title | e }}</a>

{% endif %}

The id of the map location actually "lives" in the location_id property of each object, but you won't have to deal with that directly.

Always give your joins a name starting with an underscore. This warns Apostrophe not to store this information in the database permanently where it will just take up space, then get re-joined every time anyway.

Currently after the user has selected one item they see a message reading "Limit Reached!" We realize this may not be the best way of indicating that a selection has already been made. So you may pass a limitText option with an alternative message to be displayed at this point.

What if you want to allow the user to pick anything at all, as long as it's a "regular page" in the page tree with its own permanent URL?

Just use:

withType: 'page'

This special case allows you to easily build navigation menus and the like using schema widgets and array fields.

You can also join back in the other direction:

addFields: [

{

name: '_events',

type: 'joinByOneReverse',

withType: 'event',

idField: 'locationId',

label: 'Events'

}

]

Now, in the show template for the map module, we can write:

{% for event in item._events %}

<h4><a href="{{ event.url | e }}">{{ event.title | e }}</a></h4>

{% endfor %}

"Holy crap!" Yeah, it's pretty cool.

Note that the user always edits the relationship on the "owning" side, not the "reverse" side. The event has a location_id property pointing to the map, so users pick a map location when editing an event, not the other way around.

"Won't this cause an infinite loop?" When an event fetches a location and the location then fetches the event, you might expect an infinite loop to occur. However Apostrophe does not carry out any further joins on the fetched objects unless explicitly asked to.

"What if my events are joined with promoters and I need to see their names on the location page?" If you really want to join two levels deep, you can "opt in" to those joins:

addFields: [

{

name: '_events',

// Details of the join, then...

withJoins: [ '_promoters' ]

}

]

This assumes that _promoters is a join you have already defined for events.

"What if my joins are nested deeper than that and I need to reach down several levels?"

You can use "dot notation," just like in MongoDB:

withJoins: [ '_promoters._assistants' ]

This will allow events to be joined with their promoters, and promoters to be joined with their assistants, and there the chain will stop.

You can specify more than one join to allow, and they may share a prefix:

withJoins: [ '_promoters._assistants', '_promoters._bouncers' ]

Remember, each of these later joins must actually be present in the configuration for the module in question. That is, "promoters" must have a join called "_assistants" defined in its schema.

Joins are allowed in the schema of an array field, and they work exactly as you would expect. Just include joins in the schema for the array as you normally would.

And if you are carrying out a nested join with the withJoins option, you'll just need to refer to the join correctly.

Let's say that each promoter has an array of ads, and each ad is joined to a media outlet. We're joing with events, which are joined to promoters, and we want to make sure media outlets are included in the results.

So we write:

addFields: [

{

name: '_events',

// Details of the join, then...

withJoins: [ '_promoters.ads._mediaOutlet' ]

}

]

Events can only be in one location, but stories can be in more than one book, and books also contain more than one story. How do we handle that?

Consider this configuration for a books module:

addFields: [

{

name: '_stories',

type: 'joinByArray',

withType: 'story',

idsField: 'storyIds',

sortable: true,

label: 'Stories'

}

]

Now we can access all the stories from the show template for books (or the index template, or pretty much anywhere):

<h3>Stories</h3>

{% for story in item._stories %}

<h4><a href="{{ story.url | e }}">{{ story.title | e }}</a></h4>

{% endfor %}

Since we specified sortable:true, the user can also drag the list of stories into a preferred order. The stories will always appear in that order in the ._stories property when examinining a book object.

"Many-to-many... sounds like a LOT of objects. Won't it be slow and use a lot of memory?"

It's not as bad as you think. Apostrophe typically fetches only one page's worth of items at a time in the index view, with pagination links to view more. Add the objects those are joined to and it's still not bad, given the performance of v8.

But sometimes there really are too many related objects and performance suffers. So you may want to restrict the join to occur only if you have retrieved only one book, as on a "show" page for that book. Use the ifOnlyOne option:

'stories': {

addFields: [

{

name: '_books',

withType: 'book',

ifOnlyOne: true,

label: 'Books'

}

]

}

Now any call to schema.join with only one object, or an array of only one object, will carry out the join with stories. Any call with more than one object won't.

Hint: in index views of many objects, consider using AJAX to load related objects when the user indicates interest rather than displaying related objects all the time.

Another way to speed up joins is to limit the fields that are fetched in the join. You may pass options such as fields to the get method used to actually fetch the joined objects. Note that apos.get and everything derived from it, like snippets.get, will accept a fields option which is passed to MongoDB as the projection:

'stories': {

addFields: [

{

name: '_books',

withType: 'book',

label: 'Books',

getOptions: {

fields: { title: 1, slug: 1 }

}

}

]

}

If you are just linking to things, { title: 1, slug: 1 } is a good projection to use. You can also include specific areas by name in this way.

We can also access the books from the story if we set the join up in the stories module as well:

addFields: [

{

name: '_books',

type: 'joinByArrayReverse',

withType: 'book',

idsField: 'storyIds',

label: 'Books'

}

]

}

Now we can access the ._books property for any story. But users still must select stories when editing books, not the other way around.

What if each story comes with an author's note that is specific to each book? That's not a property of the book, or the story. It's a property of the relationship between the book and the story.

If the author's note for every each appearance of each story has to be super-fancy, with rich text and images, then you should make a new module that subclasses snippets in its own right and just join both books and stories to that new module. You can also use array fields in creative ways to address this problem, using joinByOne as one of the fields of the schema in the array.

But if the relationship just has a few simple attributes, there is an easier way:

addFields: [

{

name: '_stories',

label: 'Stories',

type: 'joinByArray',

withType: 'story',

idsField: 'storyIds',

relationshipsField: 'storyRelationships',

relationship: [

{

name: 'authorsNote',

type: 'string'

}

],

sortable: true

}

]

Currently "relationship" properties can only be of type string (for text), select or boolean (for checkboxes). Otherwise they behave like regular schema properties.

Warning: the relationship field names label and value must not be used. These names are reserved for internal implementation details.

Form elements to edit relationship fields appear next to each entry in the list when adding stories to a book. So immediately after adding a story, you can edit its author's note.

Once we introduce the relationship option, our templates have to change a little bit. The show page for a book now looks like:

{% for story in item._stories %}

<h4>Story: {{ story.item.title | e }}</h4>

<h5>Author's Note: {{ story.relationship.authorsNote | e }}</h5>

{% endfor %}

Two important changes here: the actual story is story.item, not just story, and relationship fields can be accessed via story.relationship. This change kicks in when you use the relationship option.

Doing it this way saves a lot of memory because we can still share book objects between stories and vice versa.

You can do this in a reverse join too:

addFields: [

{

name: '_books',

type: 'joinByArrayReverse',

withType: 'book',

idsField: 'storyIds',

relationshipsField: 'storyRelationships',

relationship: [

{

name: 'authorsNote',

type: 'string'

}

]

}

]

Now you can write:

{% for book in item._books %}

<h4>Book: {{ book.item.title | e }}</h4>

<h5>Author's Note: {{ book.relationship.authorsNote | e }}</h5>

{% endfor %}

As always, the relationship fields are edited only on the "owning" side (that is, when editing a book).

"What is the relationshipsField option for? I don't see story_relationships in the templates anywhere."

Apostrophe stores the actual data for the relationship fields in story_relationships. But since it's not intuitive to write this in a template:

{# THIS IS THE HARD WAY #}

{% for story in book._stories %}

{{ story.item.title | e }}

{{ book.story_relationships[story._id].authorsNote | e }}

{% endif %}

Apostrophe instead lets us write this:

{# THIS IS THE EASY WAY #}

{% for story in book._stories %}

{{ story.item.title | e }}

{{ story.relationship.authorsNote | e }}

{% endif %}

Much better.

Sometimes you won't want to honor all of the joins that exist in your schema. Other times you may wish to fetch more than your schema's withJoin options specify as a default behavior.

You can force schemas.join to honor specific joins by supplying a withJoins parameter:

schemas.join(req, schema, objects, [ '_locations._events._promoters' ], callback);

The syntax is exactly the same as for the withJoins option to individual joins in the schema, discussed earlier.

You can override templates for individual fields without resorting to writing your own new.html and edit.html templates from scratch.

Here's the string.html template that renders all fields with the string type by default:

{% include "schemaMacros.html" %}

{% if textarea %}

{{ formTextarea(name, label) }}

{% else %}

{{ formText(name, label) }}

{% endif %}

You can override these for your project by creating new templates with the same names in the lib/modules/apostrophe-schemas/views folder. This lets you change the appearance for every field of a particular type. You should only override what you really wish to change.

In addition, you can specify an alternate template name for an individual field in your schema:

{ type: 'integer', name: 'shoeSize', label: 'Shoe Size', template: 'shoeSize' }

This will cause the shoeSize.html template to be rendered instead of the integer.html template.

You can also pass a render function, which receives the field object as its only parameter. Usually you'll find it much more convenient to just use a string and put your templates in lib/modules/apostrophe-schemas/views.

You can add a new field type easily.

On the server side, we'll need to write three methods:

The converter's job is to ensure the content is really a list of strings and then populate the object with it. We pull the list from data (what the user submitted) and use it to populate object. We also have access to the field name (name) and, if we need it, the entire field object (field), which allows us to implement custom options.

Your converter must not set the property to undefined or delete the property. It must be possible to distinguish a property that has been set to a value, even if that value is false or null or [], from one that is currently undefined and should therefore display the default.

Here's an example of a custom field type: a simple list of strings.

// Earlier in our module's constructor...

self._apos.mixinModuleAssets(self, 'mymodulename', __dirname, options);

// Now self.renderer is available

schemas.addFieldType({

name: 'list',

render: self.renderer('schemaList'),

converters: {

form: function(req, data, name, object, field, callback) {

// Don't trust anything we get from the browser! Let's sanitize!

var maybe = _.isArray(data[name]) ? data[name] || [];

// Now build up a list of clean content

var yes = [];

_.each(maybe, function(item) {

if (field.max && (yes.length >= field.max)) {

// Limit the length of the list via a "max" property of the field

return;

}

// Only accept strings

if (typeof(item) === 'string') {

yes.push(item);

}

});

object[name] = yes;

return setImmediate(function() {

return callback(null);

});

},

// CSV is a lot simpler because the input is always just

// a string. Split on "|" to allow more than one string in the list

csv: function(req, data, name, object, field, callback) {

object[name] = data[name].split('|');

return setImmediate(function() {

return callback(null);

});

}

}

});

We can also supply an optional indexer method to allow site-wide searches to locate this object based on the value of the field:

indexer: function(value, field, texts) {

var silent = (field.silent === undefined) ? true : field.silent;

texts.push({ weight: field.weight || 15, text: value.join(' '), silent: silent });

}

And, if our field modifies properties other than the one matching its name, we must supply a copier function so that the subsetInstance method can be used to edit personal profiles and the like:

copier: function(name, from, to, field) {

// Note: if this is really all you need, you can skip

// writing a copier

to[name] = from[name];

}

The views/schemaList.html template should look like this. Note that the "name" and "label" options are passed to the template. In fact, all properties of the field that are part of the schema are available to the template. Setting data-name correctly is crucial. Adding a CSS class based on the field name is a nice touch but not required.

<fieldset class="apos-fieldset my-fieldset-list apos-fieldset-{{ name | css}}" data-name="{{ name }}">

<label>{{ label | e }}</label>

{# Text entry for autocompleting the next item #}

<input name="{{ name | e }}" data-autocomplete placeholder="Type Here" class="autocomplete" />

{# This markup is designed for jQuery Selective to show existing list items #}

<ul data-list class="my-list">

<li data-item>

<span class="label-and-remove">

<a href="#" class="apos-tag-remove icon-remove" data-remove></a>

<span data-label>Example label</span>

</span>

</li>

</ul>

</fieldset>

Next, on the browser side, we need to supply two methods: a displayer and a converter.

"displayer" is a method that populates the form field. aposSchemas.populateFields will invoke it.

"converter" is a method that retrieves data from the form field and places it in an object. aposSchemas.convertFields will invoke it.

Here's the browser-side code to add our "list" type:

aposSchemas.addFieldType({

name: 'list',

displayer: function(data, name, $field, $el, field, callback) {

// $field is the element with right "name" attribute, which is great

// for classic HTML form elements. But for this type we want the

// div with the right "data-name" attribute. So find it in $el

$field = $el.find('[data-name="' + name + '"]');

// Use jQuery selective to power the list

$field.selective({

// pass the existing values in as label/value pairs to satisfy

// jQuery selective

data: [

_.map(data[name], function() {

return {

label: data[name],

value: data[name]

};

});

],

// Allow the user to add new strings

add: true

});

// Be sure to invoke the callback

return callback();

},

converter: function(data, name, $field, $el, field, callback) {

$field = $el.find('[data-name="' + name + '"]');

data[name] = $field.selective('get');

// Be sure to invoke the callback

return callback();

}

});

This code can live in site.js, or in a js file that you push as an asset from your project or an npm module. Make sure your module loads after apostrophe-schema.

For many applications just creating your own array of fields is fine. But if you are creating a subclass of another module that also uses schemas, and you want to adjust the schema, you'll be a lot happier if the superclass uses the schemas.compose() method to build up the schema via the addFields, removeFields, orderFields and occasionally alterFields options.

Here's a simple example:

schemas.compose({

addFields: [

{

name: 'title',

type: 'string',

label: 'Name'

},

{

name: 'age',

type: 'integer',

label: 'Age'

}

},

removeFields: [ 'age' ]

]

});

This compose call adds two fields, then removes one of them. This makes it easy for subclasses to contribute to the object which a parent class will ultimately pass to compose. It often looks like this:

var schemas = require('apostrophe-schemas');

// Superclass has title and age fields, also merges in any fields appended

// to addFields by a subclass

function MySuperclass(options) {

var self = this;

options.addFields = [

{

name: 'title',

type: 'string',

label: 'Name'

},

{

name: 'age',

type: 'integer',

label: 'Age'

}

].concat(options.addFields || []);

self._schema = schemas.compose(options);

}

// Subclass removes the age field, adds the shoe size field

function MySubclass(options) {

var self = this;

MySuperclass.call(self, {

addFields: [

{

name: 'shoeSize',

title: 'Shoe Size',

type: 'string'

}

],

removeFields: [ 'age' ]

});

}

You can also specify a removeFields option which will remove some of the fields you passed to addFields.

This is useful if various subclasses are contributing to your schema.

removeFields: [ 'thumbnail', 'body' ]

}

When adding fields, you can specify where you want them to appear relative to existing fields via the before, after, start and end options. This works great with the subclassing technique shown above:

addFields: [

{

name: 'favoriteCookie',

type: 'string',

label: 'Favorite Cookie',

after: 'title'

}

]

Any additional fields after favoriteCookie will be inserted with it, following the title field.

Use the before option instead of after to cause a field to appear before another field.

Use start: true to cause a field to appear at the top.

Use start: end to cause a field to appear at the end.

If this is not enough, you can explicitly change the order of the fields with orderFields:

orderFields: [ 'year', 'specialness' ]

Any fields you do not specify will appear in the original order, after the last field you do specify (use removeFields if you want a field to go away).

Although required: true works well, if you are subclassing and you wish to require a number of previously optional fields, the requiredFields option is more convenient. This is especially handy when working with apostrophe-moderator:

requireFields: [ 'title', 'startDate', 'body' ]

You can specify the same field twice in your addFields array. The last occurrence wins.

There is also an alterFields option available. This must be a function which receives the schema (an array of fields) as its argument and modifies it. Most of the time you will not need this option; see removeFields, addFields, orderFields and requireFields. It is mostly useful if you want to make one small change to a field that is already rather complicated. Note you must modify the existing array of fields "in place."

refineSometimes you'll want a modified version of an existing schema. schemas.refine is the simplest way to do this:

var newSchema = schemas.refine(schema, { addFields: ..., removeFields ..., etc });

The options are exactly the same as the options to compose. The returned array is a copy. No modifications are made to the original schema array.

subsetIf you just want to keep certain fields in your schema, while maintaining the same tab groups, use the subset method. This method will discard any unwanted fields, as well as any groups that are empty in the new subset of the schema:

// A subset suitable for people editing their own profiles

var profileSchema = schemas.subset(schema, [ 'title', 'body', 'thumbnail' ]);

If you wish to apply new groups to the subset, use refine and groupFields.

newInstanceThe newInstance method can be used to create an object which has the appropriate default value for every schema field:

var snowman = schemas.newInstance(snowmanSchema);

subsetInstanceThe subsetInstance method accepts a schema and an existing instance object and returns a new object with only the properties found in the given schema. This includes not just the obvious properties matching the name of each field, but also any idField or idsField properties specified by joins.

var profileSchema = schemas.subset(people.schema, [ 'title', 'body', 'thumbnail' ]);

var profile = schemas.subsetInstance(person, profileSchema);

FAQs

Schemas for easy editing of properties in Apostrophe objects

The npm package apostrophe-schemas receives a total of 33 weekly downloads. As such, apostrophe-schemas popularity was classified as not popular.

We found that apostrophe-schemas demonstrated a not healthy version release cadence and project activity because the last version was released a year ago. It has 9 open source maintainers collaborating on the project.

Did you know?

Socket for GitHub automatically highlights issues in each pull request and monitors the health of all your open source dependencies. Discover the contents of your packages and block harmful activity before you install or update your dependencies.

Security News

/Research

Malicious npm package impersonates Nodemailer and drains wallets by hijacking crypto transactions across multiple blockchains.

Security News

This episode explores the hard problem of reachability analysis, from static analysis limits to handling dynamic languages and massive dependency trees.

Security News

/Research

Malicious Nx npm versions stole secrets and wallet info using AI CLI tools; Socket’s AI scanner detected the supply chain attack and flagged the malware.