Research

Security News

Lazarus Strikes npm Again with New Wave of Malicious Packages

The Socket Research Team has discovered six new malicious npm packages linked to North Korea’s Lazarus Group, designed to steal credentials and deploy backdoors.

The time has come. Stomp your elephant1 feet on over, grab a cup of your favorite joe2, and come see3 the final word in programming language design. You'll be ready to shower this ultimate language with your finest gems4.

STOP5 is a truely modern language drawing all the benefits of old while excising their misinformed choices. STOP is founded on the principles of simplicity, clarity, and compactness. To meet these goals, STOP provides a small set of easily understood commands, only the essential set of types, and a unified state handler. STOP is a deque-based6, functional7 programming language.

A STOP machine is simple: a program is made of a list of commands and an instruction pointer. The instruction pointer starts with the first command and progresses forward, one command at a time, until it advances beyond the end of the list of commands.

In order to provide maximal effectiveness for developers, some commands move the instruction pointer in unique ways thus allowing for iteration or code reuse. Because the nature of a problem is not always known ahead of time, some commands are able to modify the set of commands. While the previous statement may make some feel uneasy, rest assured that the deque-based model that STOP is built on guarantees that commands are added in well-defined and expected locations. Note that the instruction pointer always references the command that is currently being evaluated and which is not being evaluated as part of the evaluation of a reference.

Each command has four parts: an optional label, a name, a set of arguments, and an optional comment. These parts are delimited by whitespace and, in order to avoid debate on which type of whitespace8 is best, the only valid whitespace character is the space character. Any amount of whitespace is possible before a command, after a command, or between the various parts of a command.

The canonical form of a command is

(LABEL) NAME [data1 data2 data3...] [; Comment]

Labels and command may contain the uppercase letters A-Z and the hyphen - but

may not begin or end with a hyphen.

The data in each command is evaluated sequentially left to right at the time the command is executed.

STOP has only a few types:

UNDEFINEDAn undefined value.

A numeric type. Numbers follow9 the IEEE-754 standard. A common number format for all numbers greatly simplifies arithmetic logic. There is no need to worry about signed/unsigned mismatch10 or integer to floating point conversion.

Numbers follow the patterns that a rational person would expect. Here are some example numbers:

1+22.52.75300e-20.004E3-1519940.54418e+01STOP additionally supports the following special numbers:

INFINITY+INFINITY-INFINITYNANStrings in STOP are far simpler11 than in other languages. Strings

are immutable sequences of UTF-16 code units and are delimited with ". All

characters are supported within strings including the " character itself with

proper encoding.

Here are some sample strings:

"Gut""Nylon""Fluoro carbon""Wound Metal\\Nylon""\"Open\" and \"Closed\""Lists are immutable ordered structures which contain zero or more values. Each item in a list can be any STOP type. Lists are so fundamental to writing interesting and useful programs that their existence is often times implied.

Some example lists:

[][1][1,2][1, 2, 3][["One", "two", "three"], ["Not only you and me"], ["Got", 180, "degress"], ["And I'm caught in between"]]The last data type is the one which makes STOP such a powerful language. References allow commands to accept the values returned by other commands and so enable functional12 composition across commands. References come in several different flavors13 in order to meet the needs of complex, modern requirements.

A direct reference references the value returned by a command directly. When a command directly references another command the other command is executed first and the result is used as one of the arguments to the initial command. For example, consider the program

NOOP 1 ; (1)

NOOP $0 ; (2)

Line (1) evaluates to 1. The second command, when evaluated, must first

evaluate the direct reference $0: this causes the command at index 0 to be

evaluated again and the reference is replaced by the result of that evaluation.

An indirect reference evaluates to a direct reference. These are useful when adding new commands to the program which themselves must reference other commands. Consider the program

NOOP "Don't copy" ; (1)

PUSH "NOOP" $0 ; (2)

When (2) is evaluated the direct reference is evaluated first and is replaced

with the value "Don't copy" before the rest of the command is executed. The

command which is pushed is therefore

NOOP "Don't copy"

However, it may be desirable to push a command that itself includes a direct reference. The way to accomplish this is with an indirect reference. Consider the program

NOOP "Don't copy" ; (1)

PUSH "NOOP" $$0 ; (2)

PUSH "NOOP" "Do copy" ; (3)

In this program, when (2) is evaluated the indirect reference decays into a direct reference so that the command that is pushed is

NOOP $0

If it were evaluated at the end of the program it would reference the value of

the command at index 0 and so would evaluate to "Do copy".

References may either be absolute and refer to a specific command index or may be relative and refer to a command with respect to the current position of the instruction pointer or with respect to a label.

Absolute references always take an integer. If the referenced index is greater than the number of commands in the list then the index is interpreted as if it were taken MOD the number of commands. Here are some examples:

$0: The first command$1: The second command$-1: The last command$-2: The second to last command$4: The first command in a four command program, the last command in a five

command program, and the fifth command in a six command program.Similarly, relative commands take an integer which defaults to zero if omitted and which is interpreted MOD the number of commands. Here are some examples:

$ip: The current instruction pointer$ip+0: The current instruction pointer$ip-0: The current instruction pointer$ip+1: The command directly after the current instruction pointer$ip-1: The command directly before the current instruction pointer$ci: The current command$ci+0: The current command$ci-0: The current command$ci+1: The command directly after the current command$ci-1: The command directly before the current command$FOO: The command with the label FOO$FOO+0: The command with the label FOO$FOO-0: The command with the label FOO$FOO+1: The command directly after the command with the label FOO$FOO-1: The command directly before the command with the label FOOBecause referencing the value of the current command or instruction pointer is never useful - it will lead to an infinite loop - there are six special relative references. They are:

$ip: The current value of the instruction pointer$ip+0: The current value of the instruction pointer$ip-0: The current value of the instruction pointer$ci: The position of the current command in the set of commands$ci+0: The position of the current command in the set of commands$ci-0: The position of the current command in the set of commandsReferences pull data from one location to the current command but sometimes

data from outside the program is needed. The $stdin reference reads STOP

values from the standard input stream. It is always an absolute reference.

An explicit Boolean data type is unnecessary in STOP because of the existence of truthiness. A value is truthy if it is non-empty. If it is empty then it is falsey. The falsey values are

UNDEFINEDNAN0""[]Two STOP values are equal if they have the same type and the same value. Two

lists are equal if they have the same length and if each element of one is

equal to the corresponding element of the other. NAN is unequal to

everything, including itself.

The ADD command requires at least two values and will add them together with

addition being defined depending on the types of the values. Values are added

left to right.

If value1 and value2 are both lists then value2 is concatenated to

value1. Otherwise, if value2 ia not a list then it is appended to value1.

If value2 is a list then value1 is added to each element of value2.

Otherwise, if either value1 or value2 is UNDEFINED then the result is

UNDEFINED.

If both values are numbers they are added numerically. Otherwise the values are coverted to strings and concatenated.

ADD 1 1 ; Returns 2

The ALTER command moves the first label with the given name in the list of

commands to the specified command index. The command takes a string or

UNDEFINED for the label's name and an integer representing the index to which

the label will be moved. If the label's name is UNDEFINED then the label is

removed. If the label does not yet exist, it is added.

The index is interpreted MOD the number of commands.

This command returns UNDEFINED.

ALTER "TEST" 1 ; Moves the label "TEST" to be the second command

The AND command requires will AND values together with AND being defined

depending on the types of the values. Values are ANDed left to right.

Providing the command no arguments is equivalent to providing the command with a single undefined argument.

If the command is provided a single argument then the result is whether the argument is truthy.

If the left and right values are lists then the result is the intersection of the two lists.

If the left and right values are numbers then the result is the bitwise AND of the two numbers.

Otherwise the operation returns 1 if all values are truthy and 0 otherwise.

AND 5 3 ; Returns 1

The ASNUMBER command casts its argument to a number if it is not already a

number.

If the value is missing, UNDEFINED, or a list then the result is NAN.

If the value is a string and that string is parsable as a STOP number then the result is the parsed number.

ASNUMBER "123" ; Returns 123

The ASSTING command casts its argument to a string if it is not already a

string.

ASSTRING 123 ; Returns "123"

The DIV command requires at least two values and will divide with division

being defined depending on the types of the values. Values are divided left to

right.

If any value is UNDEFINED then the result is undefined.

If any value is not a number then the result is NAN.

Otherwise the values are divided arithemtically.

The result of all other data type combinations is not a number.

DIV 18 6 ; Returns 3

The EJECT command takes no arguments and removes the last command in the list

of commands.

EJECT ; Removes the last command

The EQUAL command requires at least two values and returns 1 if all of its

arguments are equal and 0 otherwise.

EQUAL 1 1 ; Returns 1

The ERROR command converts its values into strings that can be interpreted by

STOP and outputs them as a single line to standard error.

ERROR "Oh" "teh" "noes" ; Outputs '["Oh", "teh", "noes"]'

The FLOOR command performs returns the nearest integer less than the given

value. Non-numeric values are treated as NAN.

FLOOR 3.2 ; Returns 3

The GOTO command moves the instruction pointer to the first label with the

given name in the list of commands if an optional condition is truthy. The

command takes a string for the label's name or, alternatively, an integral

index of the instruction to jump to. Indices are interpreted MOD the number

of commands so that -1 represents the last command. If the condition is not

provided then it is assumed to be truthy. If the condition is falsey then this

command does not move the instruction pointer.

This command returns UNDEFINED.

GOTO "TEST" ; Jumps to the label "TEST"

The INJECT command takes a command name and a set of values to use as the

arguments for the new command. The command is inserted as the last command in

the set of commands.

Indirect references in the set of values decay into direct references.

INJECT "GOTO" "TEST" ; Inserts the command GOTO "TEST" as the last command

The ITEM command takes a single list or string and an nonnegative number

representing an index and returns the value at that index.

If the index is out of range then UNDEFINED is returned.

ITEM [1, 2, 3] 2 ; Returns 3

The LENGTH command takes a single list or string and returns the number of

elements in that list or string.

LENGTH [1, 2, 3] ; Returns 3

The LESS command requires at least two values and returns 1 if each argument

is less than all arguments to its right and 0 otherwise.

If all values are numbers then they are compared numerically.

If all values are strings then they are compared alphabetically.

Otherwise the result is 0.

Strings are compared alphabetically.

LESS 3 2 1 ; Returns 1

The MOD command requires at least two values and will mod them with modulus

being defined depending on the types of the values. Values are modded left to

right.

If any value is UNDEFINED then the result is undefined.

If any value is not a number then the result is NAN.

Otherwise the values are modded arithemtically.

The result of all other data type combinations is not a number.

MOD 18 5 ; Returns 3

The MUL command requires at least two values and will multiple them together

with multiplication being defined depending on the types of the values. Values

are multiplied left to right.

If any value is UNDEFINED then the result is undefined.

If the right value is a nonnegative integer and the left value is a string or list then the left value is repeated according to the right value.

If the left value is a list or a string and the right value is a nonnegative integer then the list or string is concatenated with itself the specified number of times.

If all values are numbers then they are multiplied arithemtically.

Otherwise, if any value is not a number then the result is NAN.

MUL 4 5 ; Returns 20

The NEQUAL command requires at least two values and returns 0 if any of its

arguments are equal to any of its other arguments and 1 otherwise.

NEQUAL 1 1 ; Returns 0

The NOOP command returns its arguments. If no arguments are provided then the

command returns UNDEFINED. If a single argument is provided then it is

returned unchanged. If more than one argument is provided then they are

returned as a list.

NOOP 1 "one" [1] ; Returns [1, "one", [1]]

The NOT command requires will NOT values together with NOT being defined

depending on the types of the values. Values are NOTed left to right.

Providing the command no arguments is equivalent to providing the command with a single undefined argument.

If the command is provided a single finite number then the result is the bitwise inverse of the number. The number is interpreted as a 32-bit number in two's complement format.

If the command is provided a single argument that is not a finite number then the result is whether the argument is falsey.

If the left and right values are lists then the result is the set of elements in the left list that do not also exist in the right list.

Otherwise the operation returns 0.

NOT 1 ; Returns 0

The OR command requires will OR values together with OR being defined

depending on the types of the values. Values are ORed left to right.

Providing the command no arguments is equivalent to providing the command with a single undefined argument.

If the command is provided a single argument then the result is whether the argument is truthy.

If the left and right values are lists then the result is the union of the two lists with only distinct elements returned.

If the left and right values are numbers then the result is the bitwise OR of the two numbers.

Otherwise the operation returns 1 if any of the values are truthy and 0 otherwise.

OR "one" "two" ; Returns 1

The POP command takes no arguments and removes the first command in the list

of commands.

POP ; Removes the first command

The PUSH command takes a command name and a set of values to use as the

arguments for the new command. The command is inserted as the first command in

the set of commands.

Indirect references in the set of values decay into direct references.

PUSH "GOTO" "test" ; Inserts the command GOTO "test" as the first command

The SHIFT command takes a value and optionally an integer amount to shift by,

defaulting to 1. Positive amounts shift the value to the left and negative

shift the value to the right. Lists and strings are shifted by rotating the

items or characters by the given amount. UNDEFINED and non-finite numbers

always shift to themselves. Finite numbers are treated as 32-bit two's

complement numbers and are shifted bitwise. Right shifts preserve sign.

SHIFT 1 2 ; Returns 4

SHIFT 2 -1 ; Returns 1

SHIFT "test" ; Returns "estt"

The SUB command requires at least two values and will subtract them from one

another with subtraction being defined depending on the types of the values.

Values are subtracted left to right.

If any value is UNDEFINED then the result is undefined.

If the right value is a list of nonnegative integers and the left value is a string or list then the right value is interpreted as a set of indices to remove from the left value.

If all values are numbers then they are multiplied arithemtically.

Otherwise, if any value is not a number then the result is NAN.

SUB 1 2 ; Returns -1

The WRITE command converts its values into strings that can be interpreted by

STOP and outputs them as a single line to standard out.

WRITE "Hello world" ; Outputs '"Hello world"'

The STOP language is open-sourced software licensed under the MIT license

Submit a pull request. If you don't receive a response within a week, send a mail to colinjeanne@hotmail.com.

FAQs

STOP is the final word in programming language design.

The npm package stop-lang receives a total of 1 weekly downloads. As such, stop-lang popularity was classified as not popular.

We found that stop-lang demonstrated a not healthy version release cadence and project activity because the last version was released a year ago. It has 1 open source maintainer collaborating on the project.

Did you know?

Socket for GitHub automatically highlights issues in each pull request and monitors the health of all your open source dependencies. Discover the contents of your packages and block harmful activity before you install or update your dependencies.

Research

Security News

The Socket Research Team has discovered six new malicious npm packages linked to North Korea’s Lazarus Group, designed to steal credentials and deploy backdoors.

Security News

Socket CEO Feross Aboukhadijeh discusses the open web, open source security, and how Socket tackles software supply chain attacks on The Pair Program podcast.

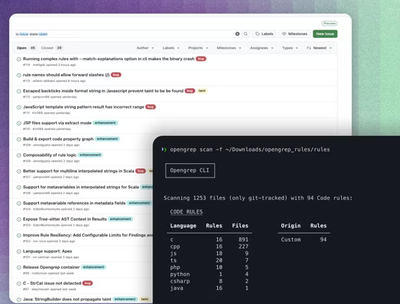

Security News

Opengrep continues building momentum with the alpha release of its Playground tool, demonstrating the project's rapid evolution just two months after its initial launch.