Security News

AGENTS.md Gains Traction as an Open Format for AI Coding Agents

AGENTS.md is a fast-growing open format giving AI coding agents a shared, predictable way to understand project setup, style, and workflows.

Spatial • Binary • Probabilistic • User-Defined Metrics

C++11 •

Python 3 •

JavaScript •

Java •

Rust •

C99 •

Objective-C •

Swift •

C# •

Go •

Wolfram

Linux • macOS • Windows • iOS • Android • WebAssembly •

SQLite

f16 & i8 - half-precision & quarter-precision support.uint40_t, accommodating 4B+ size.Technical Insights and related articles:

for-loops.FAISS is a widely recognized standard for high-performance vector search engines. USearch and FAISS both employ the same HNSW algorithm, but they differ significantly in their design principles. USearch is compact and broadly compatible without sacrificing performance, primarily focusing on user-defined metrics and fewer dependencies.

| FAISS | USearch | Improvement | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Indexing time ⁰ | |||

100 Million 96d f32, f16, i8 vectors | 2.6 · 2.6 · 2.6 h | 0.3 · 0.2 · 0.2 h | 9.6 · 10.4 · 10.7 x |

100 Million 1536d f32, f16, i8 vectors | 5.0 · 4.1 · 3.8 h | 2.1 · 1.1 · 0.8 h | 2.3 · 3.6 · 4.4 x |

| Codebase length ¹ | 84 K SLOC | 3 K SLOC | maintainable |

| Supported metrics ² | 9 fixed metrics | any metric | extendible |

| Supported languages ³ | C++, Python | 10 languages | portable |

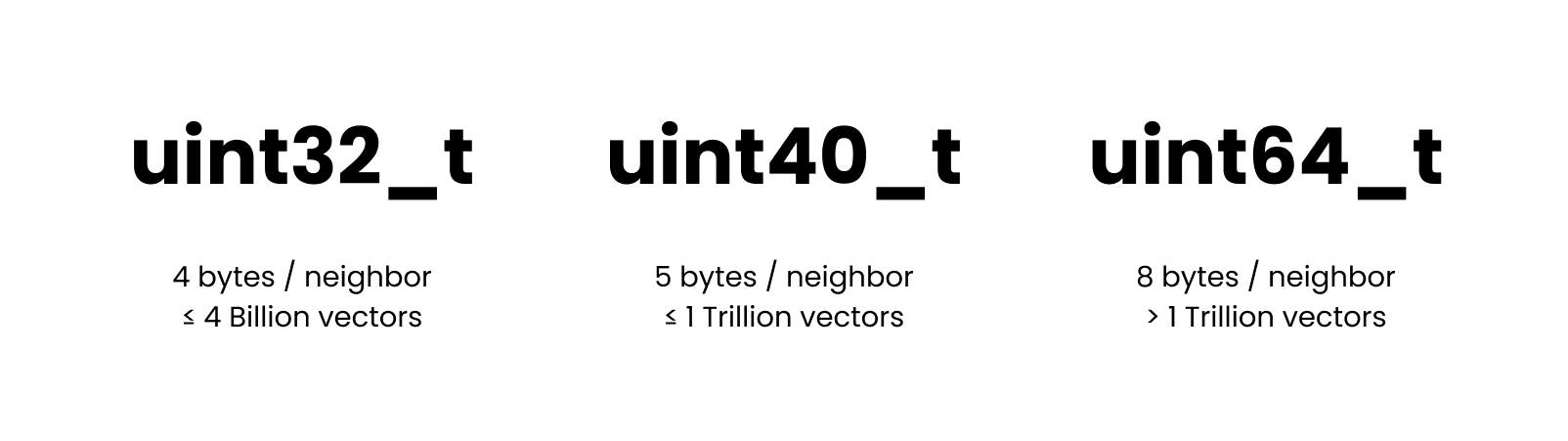

| Supported ID types ⁴ | 32-bit, 64-bit | 32-bit, 40-bit, 64-bit | efficient |

| Filtering ⁵ | ban-lists | any predicates | composable |

| Required dependencies ⁶ | BLAS, OpenMP | - | light-weight |

| Bindings ⁷ | SWIG | Native | low-latency |

| Python binding size ⁸ | ~ 10 MB | < 1 MB | deployable |

⁰ Tested on Intel Sapphire Rapids, with the simplest inner-product distance, equivalent recall, and memory consumption while also providing far superior search speed. ¹ A shorter codebase of

usearch/overfaiss/makes the project easier to maintain and audit. ² User-defined metrics allow you to customize your search for various applications, from GIS to creating custom metrics for composite embeddings from multiple AI models or hybrid full-text and semantic search. ³ With USearch, you can reuse the same preconstructed index in various programming languages. ⁴ The 40-bit integer allows you to store 4B+ vectors without allocating 8 bytes for every neighbor reference in the proximity graph. ⁵ With USearch the index can be combined with arbitrary external containers, like Bloom filters or third-party databases, to filter out irrelevant keys during index traversal. ⁶ Lack of obligatory dependencies makes USearch much more portable. ⁷ Native bindings introduce lower call latencies than more straightforward approaches. ⁸ Lighter bindings make downloads and deployments faster.

Base functionality is identical to FAISS, and the interface must be familiar if you have ever investigated Approximate Nearest Neighbors search:

# pip install usearch

import numpy as np

from usearch.index import Index

index = Index(ndim=3) # Default settings for 3D vectors

vector = np.array([0.2, 0.6, 0.4]) # Can be a matrix for batch operations

index.add(42, vector) # Add one or many vectors in parallel

matches = index.search(vector, 10) # Find 10 nearest neighbors

assert matches[0].key == 42

assert matches[0].distance <= 0.001

assert np.allclose(index[42], vector, atol=0.1) # Ensure high tolerance in mixed-precision comparisons

More settings are always available, and the API is designed to be as flexible as possible.

The default storage/quantization level is hardware-dependant for efficiency, but bf16 is recommended for most modern CPUs.

index = Index(

ndim=3, # Define the number of dimensions in input vectors

metric='cos', # Choose 'l2sq', 'ip', 'haversine' or other metric, default = 'cos'

dtype='bf16', # Store as 'f64', 'f32', 'f16', 'i8', 'b1'..., default = None

connectivity=16, # Optional: Limit number of neighbors per graph node

expansion_add=128, # Optional: Control the recall of indexing

expansion_search=64, # Optional: Control the quality of the search

multi=False, # Optional: Allow multiple vectors per key, default = False

)

Index from DiskUSearch supports multiple forms of serialization:

The latter allows you to serve indexes from external memory, enabling you to optimize your server choices for indexing speed and serving costs. This can result in 20x cost reduction on AWS and other public clouds.

index.save("index.usearch")

index.load("index.usearch")

view = Index.restore("index.usearch", view=True, ...)

other_view = Index(ndim=..., metric=...)

other_view.view("index.usearch")

Approximate search methods, such as HNSW, are predominantly used when an exact brute-force search becomes too resource-intensive.

This typically occurs when you have millions of entries in a collection.

For smaller collections, we offer a more direct approach with the search method.

from usearch.index import search, MetricKind, Matches, BatchMatches

import numpy as np

# Generate 10'000 random vectors with 1024 dimensions

vectors = np.random.rand(10_000, 1024).astype(np.float32)

vector = np.random.rand(1024).astype(np.float32)

one_in_many: Matches = search(vectors, vector, 50, MetricKind.L2sq, exact=True)

many_in_many: BatchMatches = search(vectors, vectors, 50, MetricKind.L2sq, exact=True)

If you pass the exact=True argument, the system bypasses indexing altogether and performs a brute-force search through the entire dataset using SIMD-optimized similarity metrics from SimSIMD.

When compared to FAISS's IndexFlatL2 in Google Colab, USearch may offer up to a 20x performance improvement:

faiss.IndexFlatL2: 55.3 ms.usearch.index.search: 2.54 ms.While most vector search packages concentrate on just two metrics, "Inner Product distance" and "Euclidean distance", USearch allows arbitrary user-defined metrics. This flexibility allows you to customize your search for various applications, from computing geospatial coordinates with the rare Haversine distance to creating custom metrics for composite embeddings from multiple AI models, like joint image-text embeddings. You can use Numba, Cppyy, or PeachPy to define your custom metric even in Python:

from numba import cfunc, types, carray

from usearch.index import Index, MetricKind, MetricSignature, CompiledMetric

ndim = 256

@cfunc(types.float32(types.CPointer(types.float32), types.CPointer(types.float32)))

def python_inner_product(a, b):

a_array = carray(a, ndim)

b_array = carray(b, ndim)

c = 0.0

for i in range(ndim):

c += a_array[i] * b_array[i]

return 1 - c

metric = CompiledMetric(pointer=python_inner_product.address, kind=MetricKind.IP, signature=MetricSignature.ArrayArray)

index = Index(ndim=ndim, metric=metric, dtype=np.float32)

Similar effect is even easier to achieve in C, C++, and Rust interfaces. Moreover, unlike older approaches indexing high-dimensional spaces, like KD-Trees and Locality Sensitive Hashing, HNSW doesn't require vectors to be identical in length. They only have to be comparable. So you can apply it in obscure applications, like searching for similar sets or fuzzy text matching, using GZip compression-ratio as a distance function.

Sometimes you may want to cross-reference search-results against some external database or filter them based on some criteria. In most engines, you'd have to manually perform paging requests, successively filtering the results. In USearch you can simply pass a predicate function to the search method, which will be applied directly during graph traversal. In Rust that would look like this:

let is_odd = |key: Key| key % 2 == 1;

let query = vec![0.2, 0.1, 0.2, 0.1, 0.3];

let results = index.filtered_search(&query, 10, is_odd).unwrap();

assert!(

results.keys.iter().all(|&key| key % 2 == 1),

"All keys must be odd"

);

Training a quantization model and dimension-reduction is a common approach to accelerate vector search.

Those, however, are only sometimes reliable, can significantly affect the statistical properties of your data, and require regular adjustments if your distribution shifts.

Instead, we have focused on high-precision arithmetic over low-precision downcasted vectors.

The same index, and add and search operations will automatically down-cast or up-cast between f64_t, f32_t, f16_t, i8_t, and single-bit b1x8_t representations.

You can use the following command to check, if hardware acceleration is enabled:

$ python -c 'from usearch.index import Index; print(Index(ndim=768, metric="cos", dtype="f16").hardware_acceleration)'

> sapphire

$ python -c 'from usearch.index import Index; print(Index(ndim=166, metric="tanimoto").hardware_acceleration)'

> ice

In most cases, it's recommended to use half-precision floating-point numbers on modern hardware.

When quantization is enabled, the "get"-like functions won't be able to recover the original data, so you may want to replicate the original vectors elsewhere.

When quantizing to i8_t integers, note that it's only valid for cosine-like metrics.

As part of the quantization process, the vectors are normalized to unit length and later scaled to [-127, 127] range to occupy the full 8-bit range.

When quantizing to b1x8_t single-bit representations, note that it's only valid for binary metrics like Jaccard, Hamming, etc.

As part of the quantization process, the scalar components greater than zero are set to true, and the rest to false.

Using smaller numeric types will save you RAM needed to store the vectors, but you can also compress the neighbors lists forming our proximity graphs.

By default, 32-bit uint32_t is used to enumerate those, which is not enough if you need to address over 4 Billion entries.

For such cases we provide a custom uint40_t type, that will still be 37.5% more space-efficient than the commonly used 8-byte integers, and will scale up to 1 Trillion entries.

Indexes for Multi-Index LookupsFor larger workloads targeting billions or even trillions of vectors, parallel multi-index lookups become invaluable. Instead of constructing one extensive index, you can build multiple smaller ones and view them together.

from usearch.index import Indexes

multi_index = Indexes(

indexes: Iterable[usearch.index.Index] = [...],

paths: Iterable[os.PathLike] = [...],

view: bool = False,

threads: int = 0,

)

multi_index.search(...)

Once the index is constructed, USearch can perform K-Nearest Neighbors Clustering much faster than standalone clustering libraries, like SciPy,

UMap, and tSNE.

Same for dimensionality reduction with PCA.

Essentially, the Index itself can be seen as a clustering, allowing iterative deepening.

clustering = index.cluster(

min_count=10, # Optional

max_count=15, # Optional

threads=..., # Optional

)

# Get the clusters and their sizes

centroid_keys, sizes = clustering.centroids_popularity

# Use Matplotlib to draw a histogram

clustering.plot_centroids_popularity()

# Export a NetworkX graph of the clusters

g = clustering.network

# Get members of a specific cluster

first_members = clustering.members_of(centroid_keys[0])

# Deepen into that cluster, splitting it into more parts, all the same arguments supported

sub_clustering = clustering.subcluster(min_count=..., max_count=...)

The resulting clustering isn't identical to K-Means or other conventional approaches but serves the same purpose. Alternatively, using Scikit-Learn on a 1 Million point dataset, one may expect queries to take anywhere from minutes to hours, depending on the number of clusters you want to highlight. For 50'000 clusters, the performance difference between USearch and conventional clustering methods may easily reach 100x.

One of the big questions these days is how AI will change the world of databases and data management.

Most databases are still struggling to implement high-quality fuzzy search, and the only kind of joins they know are deterministic.

A join differs from searching for every entry, requiring a one-to-one mapping banning collisions among separate search results.

| Exact Search | Fuzzy Search | Semantic Search ? |

|---|---|---|

| Exact Join | Fuzzy Join ? | Semantic Join ?? |

Using USearch, one can implement sub-quadratic complexity approximate, fuzzy, and semantic joins. This can be useful in any fuzzy-matching tasks common to Database Management Software.

men = Index(...)

women = Index(...)

pairs: dict = men.join(women, max_proposals=0, exact=False)

Read more in the post: Combinatorial Stable Marriages for Semantic Search 💍

By now, the core functionality is supported across all bindings. Broader functionality is ported per request. In some cases, like Batch operations, feature parity is meaningless, as the host language has full multi-threading capabilities and the USearch index structure is concurrent by design, so the users can implement batching/scheduling/load-balancing in the most optimal way for their applications.

| C++ 11 | Python 3 | C 99 | Java | JavaScript | Rust | Go | Swift | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Add, search, remove | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ |

| Save, load, view | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ |

| User-defined metrics | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | ❌ | ❌ | ❌ | ❌ | ❌ |

| Batch operations | ❌ | ✅ | ❌ | ✅ | ✅ | ❌ | ❌ | ❌ |

| Filter predicates | ✅ | ❌ | ✅ | ❌ | ❌ | ✅ | ❌ | ❌ |

| Joins | ✅ | ✅ | ❌ | ❌ | ❌ | ❌ | ❌ | ❌ |

| Variable-length vectors | ✅ | ❌ | ❌ | ❌ | ❌ | ❌ | ❌ | ❌ |

| 4B+ capacities | ✅ | ❌ | ❌ | ❌ | ❌ | ❌ | ❌ | ❌ |

AI has a growing number of applications, but one of the coolest classic ideas is to use it for Semantic Search. One can take an encoder model, like the multi-modal UForm, and a web-programming framework, like UCall, and build a text-to-image search platform in just 20 lines of Python.

from ucall import Server

from uform import get_model, Modality

from usearch.index import Index

import numpy as np

import PIL as pil

processors, models = get_model('unum-cloud/uform3-image-text-english-small')

model_text = models[Modality.TEXT_ENCODER]

model_image = models[Modality.IMAGE_ENCODER]

processor_text = processors[Modality.TEXT_ENCODER]

processor_image = processors[Modality.IMAGE_ENCODER]

server = Server()

index = Index(ndim=256)

@server

def add(key: int, photo: pil.Image.Image):

image = processor_image(photo)

vector = model_image(image)

index.add(key, vector.flatten(), copy=True)

@server

def search(query: str) -> np.ndarray:

tokens = processor_text(query)

vector = model_text(tokens)

matches = index.search(vector.flatten(), 3)

return matches.keys

server.run()

Similar experiences can also be implemented in other languages and on the client side, removing the network latency.

For Swift and iOS, check out the ashvardanian/SwiftSemanticSearch repository.

|

|

A more complete demo with Streamlit is available on GitHub. We have pre-processed some commonly used datasets, cleaned the images, produced the vectors, and pre-built the index.

| Dataset | Modalities | Images | Download |

|---|---|---|---|

| Unsplash | Images & Descriptions | 25 K | HuggingFace / Unum |

| Conceptual Captions | Images & Descriptions | 3 M | HuggingFace / Unum |

| Arxiv | Titles & Abstracts | 2 M | HuggingFace / Unum |

Comparing molecule graphs and searching for similar structures is expensive and slow. It can be seen as a special case of the NP-Complete Subgraph Isomorphism problem. Luckily, domain-specific approximate methods exist. The one commonly used in Chemistry is to generate structures from SMILES and later hash them into binary fingerprints. The latter are searchable with binary similarity metrics, like the Tanimoto coefficient. Below is an example using the RDKit package.

from usearch.index import Index, MetricKind

from rdkit import Chem

from rdkit.Chem import AllChem

import numpy as np

molecules = [Chem.MolFromSmiles('CCOC'), Chem.MolFromSmiles('CCO')]

encoder = AllChem.GetRDKitFPGenerator()

fingerprints = np.vstack([encoder.GetFingerprint(x) for x in molecules])

fingerprints = np.packbits(fingerprints, axis=1)

index = Index(ndim=2048, metric=MetricKind.Tanimoto)

keys = np.arange(len(molecules))

index.add(keys, fingerprints)

matches = index.search(fingerprints, 10)

That method was used to build the "USearch Molecules", one of the largest Chem-Informatics datasets, containing 7 billion small molecules and 28 billion fingerprints.

Similar to Vector and Molecule search, USearch can be used for Geospatial Information Systems. The Haversine distance is available out of the box, but you can also define more complex relationships, like the Vincenty formula, that accounts for the Earth's oblateness.

from numba import cfunc, types, carray

import math

# Define the dimension as 2 for latitude and longitude

ndim = 2

# Signature for the custom metric

signature = types.float32(

types.CPointer(types.float32),

types.CPointer(types.float32))

# WGS-84 ellipsoid parameters

a = 6378137.0 # major axis in meters

f = 1 / 298.257223563 # flattening

b = (1 - f) * a # minor axis

def vincenty_distance(a_ptr, b_ptr):

a_array = carray(a_ptr, ndim)

b_array = carray(b_ptr, ndim)

lat1, lon1, lat2, lon2 = a_array[0], a_array[1], b_array[0], b_array[1]

L, U1, U2 = lon2 - lon1, math.atan((1 - f) * math.tan(lat1)), math.atan((1 - f) * math.tan(lat2))

sinU1, cosU1, sinU2, cosU2 = math.sin(U1), math.cos(U1), math.sin(U2), math.cos(U2)

lambda_, iterLimit = L, 100

while iterLimit > 0:

iterLimit -= 1

sinLambda, cosLambda = math.sin(lambda_), math.cos(lambda_)

sinSigma = math.sqrt((cosU2 * sinLambda) ** 2 + (cosU1 * sinU2 - sinU1 * cosU2 * cosLambda) ** 2)

if sinSigma == 0: return 0.0 # Co-incident points

cosSigma, sigma = sinU1 * sinU2 + cosU1 * cosU2 * cosLambda, math.atan2(sinSigma, cosSigma)

sinAlpha, cos2Alpha = cosU1 * cosU2 * sinLambda / sinSigma, 1 - (cosU1 * cosU2 * sinLambda / sinSigma) ** 2

cos2SigmaM = cosSigma - 2 * sinU1 * sinU2 / cos2Alpha if not math.isnan(cosSigma - 2 * sinU1 * sinU2 / cos2Alpha) else 0 # Equatorial line

C = f / 16 * cos2Alpha * (4 + f * (4 - 3 * cos2Alpha))

lambda_, lambdaP = L + (1 - C) * f * (sinAlpha * (sigma + C * sinSigma * (cos2SigmaM + C * cosSigma * (-1 + 2 * cos2SigmaM ** 2)))), lambda_

if abs(lambda_ - lambdaP) <= 1e-12: break

if iterLimit == 0: return float('nan') # formula failed to converge

u2 = cos2Alpha * (a ** 2 - b ** 2) / (b ** 2)

A = 1 + u2 / 16384 * (4096 + u2 * (-768 + u2 * (320 - 175 * u2)))

B = u2 / 1024 * (256 + u2 * (-128 + u2 * (74 - 47 * u2)))

deltaSigma = B * sinSigma * (cos2SigmaM + B / 4 * (cosSigma * (-1 + 2 * cos2SigmaM ** 2) - B / 6 * cos2SigmaM * (-3 + 4 * sinSigma ** 2) * (-3 + 4 * cos2SigmaM ** 2)))

s = b * A * (sigma - deltaSigma)

return s / 1000.0 # Distance in kilometers

# Example usage:

index = Index(ndim=ndim, metric=CompiledMetric(

pointer=vincenty_distance.address,

kind=MetricKind.Haversine,

signature=MetricSignature.ArrayArray,

))

@software{Vardanian_USearch_2023,

doi = {10.5281/zenodo.7949416},

author = {Vardanian, Ash},

title = {{USearch by Unum Cloud}},

url = {https://github.com/unum-cloud/usearch},

version = {2.20.9},

year = {2023},

month = oct,

}

FAQs

Smaller & Faster Single-File Vector Search Engine from Unum

We found that usearch demonstrated a healthy version release cadence and project activity because the last version was released less than a year ago. It has 1 open source maintainer collaborating on the project.

Did you know?

Socket for GitHub automatically highlights issues in each pull request and monitors the health of all your open source dependencies. Discover the contents of your packages and block harmful activity before you install or update your dependencies.

Security News

AGENTS.md is a fast-growing open format giving AI coding agents a shared, predictable way to understand project setup, style, and workflows.

Security News

/Research

Malicious npm package impersonates Nodemailer and drains wallets by hijacking crypto transactions across multiple blockchains.

Security News

This episode explores the hard problem of reachability analysis, from static analysis limits to handling dynamic languages and massive dependency trees.