Research

/Security News

9 Malicious NuGet Packages Deliver Time-Delayed Destructive Payloads

Socket researchers discovered nine malicious NuGet packages that use time-delayed payloads to crash applications and corrupt industrial control systems.

Sarah Gooding

March 27, 2024

Last week Redis announced a shift away from open source licensing for Redis core, which will transition from the BSD 3-Clause License to a dual license approach, using the Redis Source Available License version 2 (RSALv2) or the Server Side Public License version 1 (SSPLv1) starting with Redis v7.4 and for all future releases of Redis. Neither of these licenses are approved by the OSI, and open source advocates are disappointed with this decision.

Redis supports more than 50 programming languages and boasts 4B+ Docker pulls. It is widely used in full-stack JavaScript apps to cache frequently accessed data, handle session storage, and offer real-time data updates for features like chat applications, live dashboards, collaborative editing, and communication across microservices.

Redis is frequently used for Node.js applications due to its performance and efficiency in handling concurrent connections, which aligns well with Node.js's non-blocking I/O model. There are numerous Node.js libraries and frameworks designed specifically to interact with Redis, like ioredis, which is downloaded more than 4 million times per week, making it a popular choice for developers.

Redis’ dual licensing change is permissive but not copyleft and comes with two major limitations. Users are not allowed to:

In its dual source-available licensing announcement, Redis cites the challenges of monetizing open core software in the cloud era as the reason for the shift away from open source:

The success of Redis has created a unique set of challenges. Redis has been sponsoring the bulk of development alongside a dynamic community of developers eager to contribute. However, the majority of Redis’ commercial sales are channeled through the largest cloud service providers, who commoditize Redis’ investments and its open source community. Despite efforts to support a community-led governance model, and our desire to maintain the BSD license, delivering multiple software distributions simultaneously – across open-source, source-available, and commercial software optimized for different on-premises and cloud platforms – is at odds with our ability to drive Redis successfully into the future.

The updated license forces organizations with competing offerings who leverage Redis to pay for commercial licensing when updating to newer versions. (License changes are not retroactive.) The newly adopted SSPL is based on the GNU Affero General Public License (AGPL), authored by MongoDB.

Redis stated this change should not impact users on what will soon be called Redis’ Community Edition, and they plan to backport critical security patches, as available, to existing versions under the open source license.

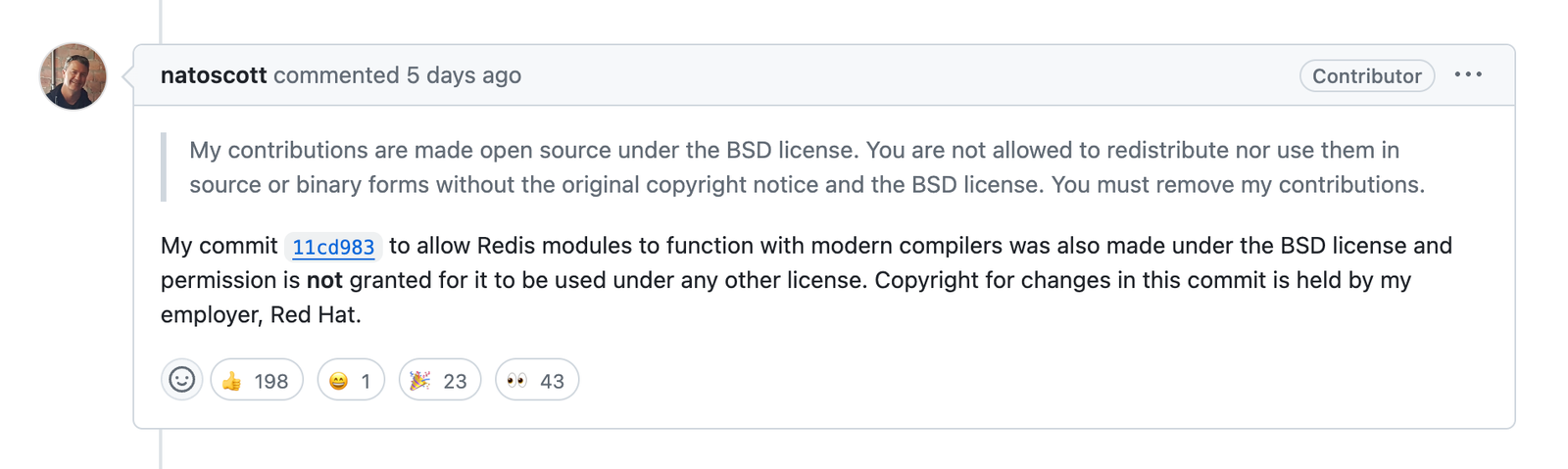

Redis opened and merged a PR last week that unilaterally changed the license from BSD-3 to dual RSALv2+SSPLv1, forcing the change against the wishes of contributors who had built the project under the assumption of an open-source future. They are angry.

Several contributors sought to redact their contributions, displeased with their code belonging to a project that is no longer open source. The permissive nature of the BSD license unfortunately allows for situations like this, where the Redis team can change the license despite a strong community preference for open source.

The PR has received more than 1,000 downvotes at the time of publishing, an indicator of how unpopular this decision was. Contributors even tried to revert the PR, with the approval of the majority of committers, but the revert was summarily closed by Redis without discussion.

Although Redis is within its rights to change the license, the community response indicates that this move is perceived as a betrayal and goes against the spirit of open source software.

“You internally agreed to remove the license,” XtremeOwnageDotCo commented. "You did not consult the community. You did not ask previous contributors if they agreed to this change.

"As a result, as we speak, Redis is being actively pinned to older versions, or just outright removed from repositories, linux distributions, etc, because you INTERNALLY decided you no longer want to do open source.

“Open source doesn't mean you get to own the code, and just take everyone's contributions for free…I would urge your leadership to go evaluate the ramifications which are currently occurring.”

In a post titled, ”RIP Redis: How Garantia Data pulled off the biggest heist in open source history,” engineer Tony Valderrama and Momento CEO Khawaja Shams explained how the company now known as Redis wasn’t involved in the open source project until years later. They wanted to use “Redis” in their company name but received pushback from the open source community. Eventually they renamed to Redis Labs and hired Redis’ creator, Salvatore “Antirez” Sanfilippo, who transferred the IP and trademark rights to them before stepping away from the project in 2020.

“A unilateral decision to upend a joint project with over a decade of love, support from a thriving community, and functional governance is a bold—dare I say reckless—transaction,” Valderrama and Shams wrote. They also contend that Redis Labs has not historically been the primary driver of innovative development in Redis, nor the primary driver of adoption, with an opinionated stance on Amazon ElastiCache taking the lead in "productionizing" Redis for large deployments.

Sanfilippo hasn’t commented on the licensing change, but it may not be in line with his vision for the project when he handed over the reins to Redis.

“I believe I’m not just leaving Redis in the hands of a community of expert programmers, but also in the hands of people who care about the legacy of the community spirit of Redis,” Sanfilippo said when he stepped back from being Redis’ maintainer four years ago.

The salt in the wound is that in 2018, Redis assured users that it “would always remain BSD” licensed. Contributors are incensed, because they gave significant time and effort to the project, believing it would remain open source, and were not consulted on the license change. They feel that Redis exploited their open source contributions only to pull the rug out from under them with a non-open source license that is now painfully fracturing the ecosystem.

“You can't just hijack work from 700+ contributors,” Tygo Egmond commented.

Many participants in the discussion on the PR are also not buying the reasoning that cloud service providers are abusing the open source community, because they know that these companies are also contributing back to the project.

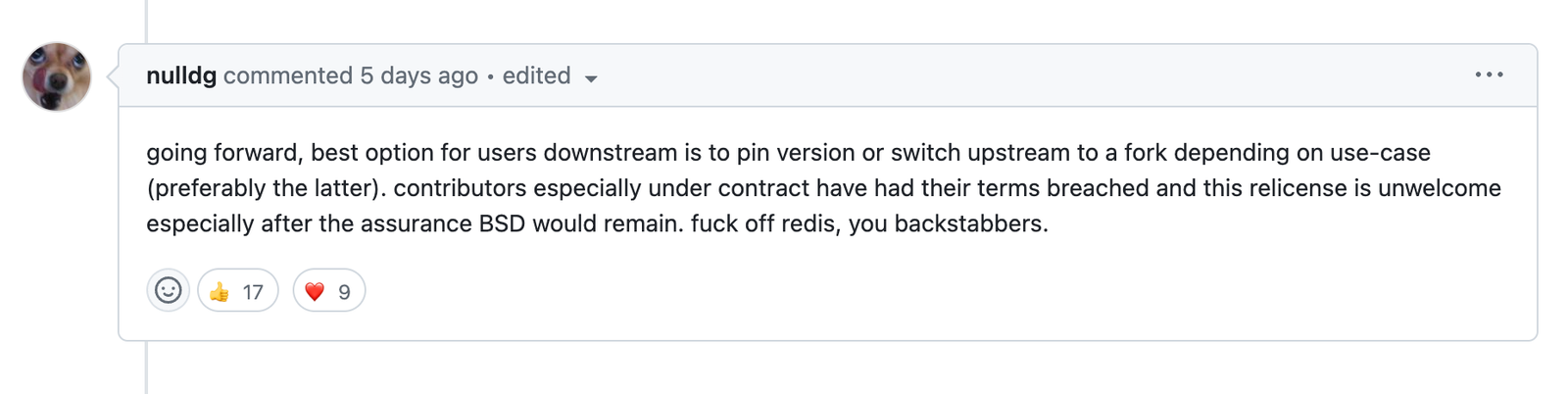

One commenter, @nulldg, mocked the notion of proprietary claims on previously open-source contributions, suggesting that these defenses are hypocritical and unconvincing within the context of OSS values:

The community is right to be irritated.

Non-free licenses are the enemy of FOSS no matter how you shake it. OSS is fundamentally altruistic, so none of us care how many competitors Redis has. Copying is not theft but relicensing open source contributions without permission is. Doing so stands in grave contrast to the philosophy of sharing under which these third-party developers contributed in the first place.

“Don't steal from me what I have stolen" just isn't a very convincing defense.

Others noted that Redis profited off of the contributions from cloud providers who sponsored employees to work on the open source project.

“You forgot that those competitors like AWS contributed to Redis development (see Pull requests of @madolson who works on AWS),” @ThaFireDragonOfDeath commented. “So in my eyes it looks like Redis is now backstabbing after it profited from the community which includes cloud service providers.”

The comments on the PR immediately turned to discussions on viable forks and the logistics of where to host the fork. Redis is not the first to abandon open source licensing and find an emerging fork on the heels this change.

In 2021, Elasticsearch followed a similar path to dual-licensing, blaming Amazon for the change. In a painfully similar scenario, Elasticsearch had also gone back on the promise they made in 2018 to never change the license of any of the Apache 2.0 code of Elasticsearch, Kibana, Beats, and Logstash projects.

At that time, the Open Source Initiative (OSI) reacted to the news of Elasticsearch’s license change, calling the SSPL a “fauxpen” source license:

Fauxpen source licenses allow a user to view the source code but do not allow other highly important rights protected by the Open Source Definition, such as the right to make use of the program for any field of endeavor. By design, and as explained by the most recent adopter, Elastic, in a post it unironically titled “Doubling Down on Open,” Elastic says that it now can “restrict cloud service providers from offering our software as a service” in violation of OSD6. Elastic didn’t double down, it threw its cards in.

Amazon successfully forked Elasticsearch, leading to the creation of OpenSearch as an open-source alternative. Similarly, following HashiCorp's decision in August 2023, to adopt a more restrictive license, a significant portion of the Terraform community has coalesced around OpenTofu as an alternative.

Relicensing in a way that removes key freedoms of the previous license usually angers the contributor base, and they often end up partnering with the larger corporations that continue to champion OSS.

Redis forks are already popping up and gaining momentum. Madelyn Olson, Principal Engineer at Amazon ElastiCache, was a sponsored contributor to Redis with 6,004 lines of active code in the project and 128 commits. She is working with former Redis contributors on a fork, which has a temporary placeholder name until they decide on a permanent one.

“We are all unhappy with the license change, and are looking to build a new truly open community to fill the void left by Redis,” Olson said on X.

“I worked on OSS Redis for 6 years, 4 as one of the core team members that drove Redis open source until 7.2. I care deeply about open source software, and want to keep contributing. I didn't see another option I liked.

“There was a lot of ongoing development and projects that just got blindsided by this. I know technically Redis is allowed to do this, but they should feel ashamed for how they handled [it].

"We had a really exciting community roadmap before Redis changed the license. Clustering improvements, performance improvements, triggers, and so much more. We'll keep driving this forward.”

Olson said her fork’s contributors are working on an initial compatibility release and plan to publish their roadmap soon. She emphasized that this is not an AWS fork and that an official response from AWS is also forthcoming.

"AWS is aware of what I'm doing, and is preparing their own response,” she said.

Software developer and open source maintainer Drew DeVault has launched another fork in a post titled Redict is an independent, copyleft fork of Redis®. Redict will use the LGPL, a copyleft license that guarantees that modified versions are distributed under the same license.

“The main concern is changing the name in a backwards-compatible manner and establishing a technical foundation for an independent future,” DeVault said. His intention is to take a conservative approach by providing a continuation of the OSS development on the project “with minimally disruptive changes for the time being.”

Olson responded to questions about Redict, saying the vision “is ultimately not closely aligned with what I want. I want to continue investing heavily in new features, as we were doing before the license change. Drew seemed more aligned with building a fundamentally FOSS project that is out quickly.”

The forks are most applicable to organizations providing Redis as a service, but OSS advocates and contributors may also be more ideologically aligned with a fork moving forward. These forks are not simply a rename for public companies that have built services on top of OSS Redis - they are an affirmation of the core principles of open source stewardship and the collective rejection of a single entity monopolizing community efforts.

“I’m inclined to figure out how to get whatever replaces the Redis community into a foundation,” Olson commented on X. “This rug pull is so damaging. I thought Redis understood the value of good stewardship, but what's clear is you can't trust one company with a community.”

This trend of open source projects relicensing, claiming they were forced by the actions of cloud providers, creates tectonic shifts in how OSS contributors decide to invest their efforts. Some are speculating that Redis was caving to investors pressuring them to make the cloud market pay.

“‘I only do open source work if I am the only one making the buck’ is not what open source should be,” @lannistersstark commented on Reddit.

“Open source licenses are supposed to enable and foster competitors, not restrict them. The Entire point of OSS is that open source software be altruistic, and not discriminate among people as to who may use it and for what purpose.”

“Quantitative tightening and the drying up of VC is making a lot of commercial software vendors reconsider open-core strategies,” @flmontpetit commented on Reddit. “This shouldn't come as a surprise. Redis was 'free’ in the same sense that YouTube content is only ‘free’ because it's an effective vehicle for advertisement. Redis was only ‘open source’ in order to corral users towards the company's cloud and enterprise licenses.”

Many OSS advocates perceive Redis’ move as what DeVault called “a transparent and poorly justifiable cash grab that offends our sensibilities,” but he urged contributors to examine how they can better assert their values to prevent these catastrophes.

“This is a traumatic moment for the Redis community, but also for the free software community,” DeVault said. “This has happened too many times: MongoDB, ElasticSearch, now Redis, and many other projects, hell, even Solaris, and many projects with commercial stewards are transparently keeping the same strategy in their back pocket with CLAs and copyright assignments from contributors.

“We could just repeat history, gather the diaspora, and try to rally behind a hastily made fork, throw it up on GitHub, BSD license it, get the commercial interests on board, and press on like everything is normal. But, I think that this is an important moment to question our values, and how we ended up here, and what kind of changes we need to make to curtail this trend.”

Subscribe to our newsletter

Get notified when we publish new security blog posts!

Try it now

Research

/Security News

Socket researchers discovered nine malicious NuGet packages that use time-delayed payloads to crash applications and corrupt industrial control systems.

Security News

Socket CTO Ahmad Nassri discusses why supply chain attacks now target developer machines and what AI means for the future of enterprise security.

Security News

Learn the essential steps every developer should take to stay secure on npm and reduce exposure to supply chain attacks.