Security News

PyPI’s New Archival Feature Closes a Major Security Gap

PyPI now allows maintainers to archive projects, improving security and helping users make informed decisions about their dependencies.

Pensieve is a Python library for organizing objects and dependencies in a graph structure.

"One simply siphons the excess thoughts from one's mind, pours them into the basin, and examines them at one's leisure. It becomes easier to spot patterns and links, you understand, when they are in this form."

—Albus Dumbledore (Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire by J. K. Rowling)

In J. K. Rowling's words: "a witch or wizard can extract their own or another's memories, store them in the Pensieve, and review them later. It also relieves the mind when it becomes cluttered with information. Anyone can examine the memories in the Pensieve, which also allows viewers to fully immerse themselves in the memories".

Dealing with data during data wrangling and model generation in data science is like dealing with memories except that there is a lot more of back and forth and iteration when dealing with data. You constantly update parameters of your models, improve your data wrangling, and make changes to the ways you visualize or store data. As with most processes in data science, each step along the way may take a long time to finish which forces you to avoid rerunning everything from scratch; this approach is very error-prone as some of the processes depend on others. To solve this problem I came up with the idea of a Computation Graph where the nodes represent data objects and the direction of edges indicate the dependency between them.

After using Pensieve for some time myself, I have found it to be beneficial in several ways:

Using pensieve is similar to using a dictionary:

from pensieve import Pensieve

from math import pi

# initiate a pensieve

pensieve = Pensieve()

# store a "memory" (with 1 as its content)

pensieve['radius'] = 5

# create a new memory made up of a precursor memory

# it is as easy as passing a defined function or a lambda to pensieve

pensieve['circumference'] = lambda radius: 2 * pi * radius

print(pensieve['circumference'])

outputs:

31.41592653589793

Changing the radius, in this example, will affect the circumference but it is only calculated when needed:

pensieve['radius'] = 6

print(pensieve['circumference'])

outputs

37.69911184307752

pip install pensieve

Pensieve stores memories and functions that define the relationship between memories.

A Pensieve is a computation graph where the nodes hold values and edges

show dependency between nodes. Each node is called a Memory.

Every memory has two important attributes:

key: the name of the memory which should be identicalcontent: the object the memory holdsSome memories have two other attributes:

precursors: other memories a memory depends onfunction: a function that defines the relationship between a memory

and its precursorsThere are two types of memories:

As explained above, you can work with pensieve similar to how you use a

dictionary. Adding a new item, i.e., a memory and its content, to pensieve is

called storing. In fact the Pensieve class has a store method which

can be used for storing new memories. However, we only use it for advanced

functionality. We do not use it as frequently because a new simpler notation

introduced since version 2 makes working pensieve much more coherent.

We will explain the store method and its notation in the Advanced Usage section.

Retrieving the content of a memory is like getting an item from a dictionary.

print(pensieve['circumference'])

An independent memory is like a root node in pensieve. It holds an object and it does not depend on any other memory.

from pensieve import Pensieve

pensieve = Pensieve()

pensieve['text'] = 'Hello World!'

pensieve['number'] = 1

pensieve['list_of_numbers'] = [1, 3, 2]

In the above example, text, number, and list are the names of three

independent memories and their contents are

the string 'Hello World',

the integer 1,

and a list consisting of three integers.

A dependent memory is created from running a function on other dependent or independent memories as the function's arguments. We call those memories, precursors; i.e., if a memory depends on another memory, the former is a dependent memory and the latter is its precursor.

The easiest way to define a dependent memory is by passing a function to pensieve whose arguments match the names of precursors.

def print_and_return_first_word(text):

words = text.split()

print(words[0])

return words[0]

pensieve['first_word'] = print_and_return_first_word

In the above example, the print_and_return_first_word function accepts one argument:

text which is the name of the precursor.

You can also use a lambda, when possible, to define a dependent memory.

pensieve['sorted_list'] = lambda list_of_numbers: sorted(list_of_numbers)

Memories that depend on a memory are its successors. If a precursor is like a parent, a successor is like a child.

In the above example, sorted_list is a successor of list_of_numbers.

If one or more precursors of a memory change, the memory and all its successors becomes stale. A stale memory is only refreshed when needed and if after calculation, it is found out that the content has not changed, the successors go back to being up-to-date, but if the content has in fact changed, the stay stale and will be updated when needed.

Note: if a memory is stale, retrieving its content will update it.

from pensieve import Pensieve

from pandas import DataFrame, concat

from numpy.random import randint, seed

# set seed for the randint function

seed(17)

# set up a pensieve with a top-bottom (tb) representation

# the top-bottom graph_direction is purely aesthetic

# you can also use lr for left to right or rl for right to left or bottom-top

pensieve = Pensieve(graph_direction='tb')

# choose the number of columns for two dataframes

pensieve['number_of_columns'] = 9

# create generic names for the columns, in this case x_1, x_2, ...

pensieve['column_names'] = lambda number_of_columns: [

f'x_{i + 1}' for i in range(number_of_columns)

]

# choose the range of random values, and store them as a dictionary

pensieve['value_range'] = {'low': 1, 'high': 5}

# define a function that creates a dataframe with the above parameters

def create_dataframe(column_names, value_range, number_of_rows):

return DataFrame({

column: randint(

low=value_range['low'],

high=value_range['high'],

size=number_of_rows

)

for column in column_names

})

# create the first dataframe

pensieve['data_1'] = lambda column_names, value_range: create_dataframe(

column_names=column_names, value_range=value_range, number_of_rows=5

)

# create the second dataframe

pensieve['data_2'] = lambda column_names, value_range: create_dataframe(

column_names=column_names, value_range=value_range, number_of_rows=3

)

# concatenate the two dataframes

pensieve['data_1_and_2'] = lambda data_1, data_2: concat(

objs=[data_1, data_2],

sort=False

)

# choose a coefficient for a future multiplication

pensieve['coefficient'] = 5

# define a function that sums all the values in each row and

# multiplies the result by the coefficient

def sum_and_multiply(data_1_and_2, coefficient):

data = data_1_and_2.copy()

data['summation'] = data.apply(sum, axis=1)

data['coefficient'] = coefficient

data['y'] = data['summation'] * data['coefficient']

return data

# get the result of the sum_and_multiply function

pensieve['result'] = sum_and_multiply

# display the pensieve

display(pensieve)

# or simply pensieve at the end of a jupyter notebook cell

from pensieve import Pensieve

from time import sleep

from datetime import datetime

# as in other libraries, num_threads=-1 means

# using as many threads as available

start_time = datetime.now()

pensieve = Pensieve(num_threads=-1, evaluate=False)

pensieve['x'] = 1

pensieve['y'] = 10

pensieve['z'] = 2

pensieve['w'] = 20

def add_with_delay(x, y):

print(f'adding {x} and {y}, slowly, at {datetime.now()}')

sleep(1)

return x + y

pensieve['x_plus_y'] = add_with_delay

pensieve['z_plus_w'] = lambda z, w: add_with_delay(x=z, y=w)

# we had to use a lambda for this one because the arguments

# of the add_with_delay function are different

pensieve['all_the_four'] = lambda x_plus_y, z_plus_w: add_with_delay(x=x_plus_y, y=z_plus_w)

elapsed = datetime.now() - start_time

print('Nothing has been calculated yet. Elapsed time:', elapsed)

print('Getting all_the_four forces the calculation of everything')

start_time = datetime.now()

print('Result of adding the four numbers:', pensieve['all_the_four'])

elapsed = datetime.now() - start_time

print('Elapsed time:', elapsed)

The above code produces the following output:

Nothing has been calculated yet. Elapsed time: 0:00:00.000716

Getting all_the_four forces the calculation of everything

adding 2 and 20, slowly, at 2019-12-15 21:33:55.063888

adding 1 and 10, slowly, at 2019-12-15 21:33:55.064526

adding 11 and 22, slowly, at 2019-12-15 21:33:56.188258

Result of adding the four numbers: 33

Elapsed time: 0:00:02.341677

Two of the calculations were executed in parallel: x + y and z + w.

With an overhead of 0.34 seconds, the three calculations took 2.34 seconds.

Let's see what happens if we do it the ordinary way:

start_time = datetime.now()

x = 1

y = 10

z = 2

w = 20

x_plus_y = add_with_delay(x, y)

z_plus_w = add_with_delay(z, w)

all_the_four = add_with_delay(x_plus_y, z_plus_w)

print('Result of adding the four numbers:', all_the_four)

elapsed = datetime.now() - start_time

print('Elapsed time:', elapsed)

This time the following output is produced:

adding 1 and 10, slowly, at 2019-12-15 21:38:11.618910

adding 2 and 20, slowly, at 2019-12-15 21:38:12.620105

adding 11 and 22, slowly, at 2019-12-15 21:38:13.625195

Result of adding the four numbers: 33

Elapsed time: 0:00:03.011291

With an overhead of 0.01 seconds, the three calculations

ran one after the other and took 3.01 seconds.

store MethodTBD

FAQs

Python library for organizing objects and dependencies in a graph structure

We found that pensieve demonstrated a healthy version release cadence and project activity because the last version was released less than a year ago. It has 1 open source maintainer collaborating on the project.

Did you know?

Socket for GitHub automatically highlights issues in each pull request and monitors the health of all your open source dependencies. Discover the contents of your packages and block harmful activity before you install or update your dependencies.

Security News

PyPI now allows maintainers to archive projects, improving security and helping users make informed decisions about their dependencies.

Research

Security News

Malicious npm package postcss-optimizer delivers BeaverTail malware, targeting developer systems; similarities to past campaigns suggest a North Korean connection.

Security News

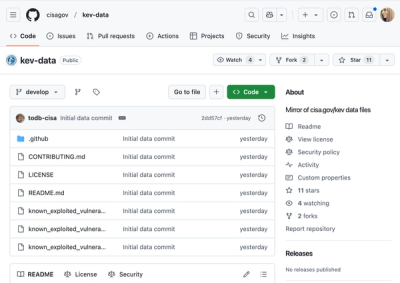

CISA's KEV data is now on GitHub, offering easier access, API integration, commit history tracking, and automated updates for security teams and researchers.