Security News

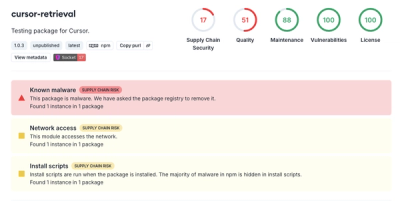

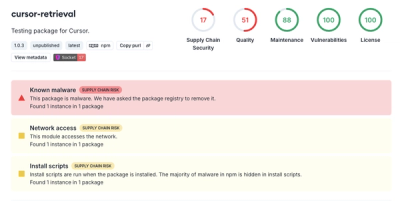

The Risks of Misguided Research in Supply Chain Security

Snyk's use of malicious npm packages for research raises ethical concerns, highlighting risks in public deployment, data exfiltration, and unauthorized testing.

github.com/code-review-checklists/java-concurrency

Design

Documentation

ConcurrentHashMap is not stored in a variable of Map type?compute()-like methods are not called on a variable of ConcurrentMap type?@GuardedBy annotation is used?volatile is justified?volatile nor annotated with @GuardedBy has a comment?

Insufficient synchronization

@Get/@Post methods are thread-safe?

DateFormat.parse() and format() are synchronized?Excessive thread safety

get() and set() are called?ReentrantLock (ReentrantReadWriteLock, Semaphore) needs to be fair?Race conditions

put() or remove() calls on a ConcurrentMap (or Cache) after get() or

containsKey()?Collections.unmodifiable*() from

a getter in a thread-safe class?coll.toArray(new E[coll.size()]) is not called on a synchronized collection?

invalidate(key) and get() calls on Guava's loading Cache?

Cache.put() is not used (nor exposed in the own Cache interface)?Collections.synchronized*() collection is protected

by the lock?containsAll(), addAll(), removeAll(), or

putAll() under the lock?Testing

Random instance is not used from concurrent test workers?CountDownLatch.await()?Locks

wait (await) calls?

Monitor instead of a lock with conditional wait (await) calls?

synchronized instead of a ReentrantLock?lock() is called outside of try {}? No statements between lock() and try {}?

Avoiding deadlocks

ConcurrentHashMap's methods (incl. get()) in compute()-like lambdas on the

same map?Improving scalability

ConcurrentHashMap.compute() or Guava's Striped for per-key locking?

ClassValue instead of ConcurrentHashMap<Class, ...>?ReadWriteLock (or StampedLock) instead of a simple lock?StampedLock is used instead of ReadWriteLock when reentrancy is not needed?

LongAdder instead of an AtomicLong for a "hot field"?

ForkJoinPool instead of newFixedThreadPool(N)?Lazy initialization and double-checked locking

Non-blocking and partially blocking code

Thread.yield() and Thread.onSpinWait() are justified?

Threads and Executors

ExecutorService instead of creating a new Thread each time some method is called?

ForkJoinPool or in a parallel Stream pipeline?

FJP.commonPool() instead of a custom thread pool?

ExecutorService is shut down explicitly?CompletableFuture (SettableFuture) in non-async mode only if

either:

CompletableFuture (SettableFuture) in non-async mode is justified?

ScheduledExecutorService rather than Thread.sleep()?

awaitTermination()?ExecutorService is not assigned into a variable of Executor

type?ScheduledExecutorService is not assigned into a variable of ExecutorService

type?Parallel Streams

Futures

Future?Future doesn't block?Future, considered wrapping an "expected" exception as a failed

Future?Thread interruption and Future cancellation

InterruptedException with another exception?

InterruptedException is swallowed only in the following kinds of methods:

Runnable.run(), Callable.call(), or methods to be passed to executors as lambda tasks; orInterruptedException swallowing is documented for a method?Uninterruptibles to avoid InterruptedException swallowing?

Future is canceled upon catching an InterruptedException or a TimeoutException on get()?

Time

nanoTime() values are compared in an overflow-aware manner?currentTimeMillis() is not used to measure time intervals and timeouts?

TimeUnit?ScheduledThreadPoolExecutor?ScheduledThreadPoolExecutor?ThreadLocal

ThreadLocal can be static final?ThreadLocal (esp. non-static one)?

ThreadLocal is not used just to avoid moderate amount of allocation?

ThreadLocal with an instance-confined Map<Thread, ...>?

Thread safety of Cleaners and native code

close() is concurrently idempotent in a class with a Cleaner or finalize()?

reachabilityFence() in a class with a Cleaner or

finalize()?Cleaner or finalize() is used for real cleanup, not mere reporting?# Dn.1. If the patch introduces a new subsystem (class, method) with concurrent code, is the necessity for concurrency or thread safety rationalized in the patch description? Is there a discussion of alternative design approaches that could simplify the concurrency model of the code (see the next item)?

A way to nudge thinking about concurrency design is demanding the usage of concurrency tools and language constructs to be justified in comments.

See also an item about unneeded thread-safety of classes and methods.

# Dn.2. Is it possible to apply one or several design patterns (some of them are listed below) to significantly simplify the concurrency model of the code, while not considerably compromising other quality aspects, such as overall simplicity, efficiency, testability, extensibility, etc?

Immutability/Snapshotting. When some state should be updated, a new immutable object (or a

snapshot within a mutable object) is created, published and used, while some concurrent threads may

still use older copies or snapshots. See [EJ Item 17], [JCIP 3.4], RC.5 and

NB.2, CopyOnWriteArrayList, CopyOnWriteArraySet, persistent data

structures.

Divide and conquer. Work is split into several parts that are processed independently, each part

in a single thread. Then the results of processing are combined. Parallel

Streams or ForkJoinPool (see TE.4 and

TE.5) can be used to apply this pattern.

Producer-consumer. Pieces of work are transmitted between worker threads via queues. See [JCIP 5.3], Dl.1, CSP, SEDA.

Instance confinement. Objects of some root type encapsulate some complex hierarchical child state. Root objects are solitarily responsible for the safety of accesses and modifications to the child state from multiple threads. In other words, composed objects are synchronized rather than synchronized objects are composed. See [JCIP 4.2, 10.1.3, 10.1.4]. RC.3, RC.4, and RC.5 describe race conditions that could happen to instance-confined state. TL.4 touches on instance confinement of thread-local state.

Thread/Task/Serial thread confinement. Some state is made local to a thread using top-down

pass-through parameters or ThreadLocal. See [JCIP 3.3] and the checklist section about

ThreadLocals. Task confinement is a variation of the

idea of thread confinement that is used in conjunction with the divide-and-conquer pattern. It

usually comes in the form of lambda-captured "context" parameters or fields in the per-thread task

objects. Serial thread confinement is an extension of the idea of thread confinement for the

producer-consumer pattern, see [JCIP 5.3.2].

Active object. An object manages its own ExecutorService or Thread to do the work. See the

article on Wikipedia and TE.6.

# Dc.1. For every class, method, and field that has signs of being thread-safe,

such as the synchronized keyword, volatile modifiers on fields, use of any classes from

java.util.concurrent.*, or third-party concurrency primitives, or concurrent collections: do their

Javadoc comments include

The justification for thread safety: is it explained why a particular class, method or field has to be thread-safe?

Concurrent access documentation: is it enumerated from what methods and in contexts of what threads (executors, thread pools) each specific method of a thread-safe class is called?

Wherever some logic is parallelized or the execution is delegated to another thread, are there comments explaining why it’s worse or inappropriate to execute the logic sequentially or in the same thread? See PS.1 regarding this.

See also NB.3 and NB.4 regarding justification of non-blocking code, racy code, and busy waiting.

If the usage of concurrency tools is not justified, there is a possibility of code ending up with

unnecessary thread-safety, redundant atomics,

redundant volatile modifiers, or unneeded Futures.

# Dc.2. If the patch introduces a new subsystem that uses threads or thread

pools, are there high-level descriptions of the threading model, the concurrent control flow (or

the data flow) of the subsystem somewhere, e. g. in the Javadoc comment for the package in

package-info.java or for the main class of the subsystem? Are these descriptions kept up-to-date

when new threads or thread pools are added or some old ones deleted from the system?

Description of the threading model includes the enumeration of threads and thread pools created and

managed in the subsystem, and external pools used in the subsystem (such as

ForkJoinPool.commonPool()), their sizes and other important characteristics such as thread

priorities, and the lifecycle of the managed threads and thread pools.

A high-level description of concurrent control flow should be an overview and tie together concurrent control flow documentation for individual classes, see the previous item. If the producer-consumer pattern is used, the concurrent control flow is trivial and the data flow should be documented instead.

Describing threading models and control/data flow greatly improves the maintainability of the system, because in the absence of descriptions or diagrams developers spend a lot of time and effort to create and refresh these models in their minds. Putting the models down also helps to discover bottlenecks and the ways to simplify the design (see Dn.2).

# Dc.3. For classes and methods that are parts of the public API or the extensions API of the project: is it specified in their Javadoc comments whether they are (or in case of interfaces and abstract classes designed for subclassing in extensions, should they be implemented as) immutable, thread-safe, or not thread-safe? For classes and methods that are (or should be implemented as) thread-safe, is it documented precisely with what other methods (or themselves) they may be called concurrently from multiple threads? See also [EJ Item 82], [JCIP 4.5], CON52-J.

If the @com.google.errorprone.annotations.Immutable annotation is used to mark immutable classes,

Error Prone static analysis tool is capable to detect when a class is

not actually immutable (see a relevant bug

pattern).

# Dc.4. For subsystems, classes, methods, and fields that use some concurrency design patterns, either high-level, such as those mentioned in Dn.2, or low-level, such as double-checked locking or spin looping: are the used concurrency patterns pronounced in the design or implementation comments for the respective subsystems, classes, methods, and fields? This helps readers to make sense out of the code quicker.

Pronouncing the used patterns in comments may be replaced with more succinct documentation

annotations, such as @Immutable (Dc.3), @GuardedBy

(Dc.7), @LazyInit (LI.5), or annotations that you define

yourself for specific patterns which appear many times in your project.

# Dc.5. Are ConcurrentHashMap and ConcurrentSkipListMap objects stored

in fields and variables of ConcurrentHashMap or ConcurrentSkipListMap or ConcurrentMap

type, but not just Map?

This is important, because in code like the following:

ConcurrentMap<String, Entity> entities = getEntities();

if (!entities.containsKey(key)) {

entities.put(key, entity);

} else {

...

}

It should be pretty obvious that there might be a race condition because an entity may be put into

the map by a concurrent thread between the calls to containsKey() and put() (see

RC.1 about this type of race conditions). While if the type of the entities variable

was just Map<String, Entity> it would be less obvious and readers might think this is only

slightly suboptimal code and pass by.

It’s possible to turn this advice into an inspection in IntelliJ IDEA.

# Dc.6. An extension of the previous item: are ConcurrentHashMaps on which compute(),

computeIfAbsent(), computeIfPresent(), or merge() methods are called stored in fields and

variables of ConcurrentHashMap type rather than ConcurrentMap? This is because

ConcurrentHashMap (unlike the generic ConcurrentMap interface) guarantees that the lambdas

passed into compute()-like methods are performed atomically per key, and the thread safety of the

class may depend on that guarantee.

This advice may seem to be overly pedantic, but if used in conjunction with a static analysis rule

that prohibits calling compute()-like methods on ConcurrentMap-typed objects that are not

ConcurrentHashMaps (it’s possible to create such inspection in IntelliJ IDEA too) it could prevent

some bugs: e. g. calling compute() on a ConcurrentSkipListMap might be a race condition and

it’s easy to overlook that for somebody who is used to rely on the strong semantics of compute()

in ConcurrentHashMap.

# Dc.7. Is @GuardedBy annotation used? If accesses to some fields should be

protected by some lock, are those fields annotated with @GuardedBy? Are private methods that are

called from within critical sections in other methods annotated with @GuardedBy? If the project

doesn’t depend on any library containing this annotation (it’s provided by jcip-annotations, error_prone_annotations, jsr305, and other libraries) and

for some reason it’s undesirable to add such dependency, it should be mentioned in Javadoc comments

for the respective fields and methods that accesses and calls to them should be protected by some

specified locks.

See [JCIP 2.4] for more information about @GuardedBy.

Usage of @GuardedBy is especially beneficial in conjunction with Error Prone tool which is able to statically check for unguarded accesses to fields

and methods with @GuardedBy annotations. There is

also an inspection "Unguarded field access" in IntelliJ IDEA with the same effect.

# Dc.8. If in a thread-safe class some fields are accessed both from within critical sections and outside of critical sections, is it explained in comments why this is safe? For example, unprotected read-only access to a reference to an immutable object might be benignly racy (see RC.5). Answering this question also helps to prevent problems described in IS.2, IS.3, and RC.2.

Instead of writing a comment explaining that access to a lazily initialized field outside of a

critical section is safe, the field could just be annotated with @LazyInit from

error_prone_annotations (but make

sure to read the Javadoc for this annotation and to check that the field conforms to the

description; LI.3 and LI.5 mention potential pitfalls).

Apart from the explanations why the partially blocking or racy code is safe, there should also be comments justifying such error-prone code and warning the developers that the code should be modified and reviewed with double attention: see NB.3.

There is an inspection "Field accessed in both synchronized and unsynchronized contexts" in IntelliJ IDEA which helps to find classes with unbalanced synchronization.

# Dc.9. Regarding every field with a volatile modifier: does it really need

to be volatile? Does the Javadoc comment for the field explain why the semantics of volatile

field reads and writes (as defined in the Java Memory Model) are required for the

field?

Similarly to what is noted in the previous item, justification for a lazily initialized field to be

volatile could be omitted if the lazy initialization pattern itself is identified, according to

Dc.4. When volatile on a field is needed to ensure safe publication of

objects written into it (see [JCIP 3.5] or here) or

linearizability of values observed by reader threads, then just mentioning

"safe publication" or "linearizable reads" in the Javadoc comment for the field is sufficient, it's

not needed to elaborate the semantics of volatile which ensure the safe publication or the

linearizability.

By extension, this item also applies when an AtomicReference (or a primitive atomic) is used

instead of raw volatile, along with the consideration about unnecessary

atomic which might also be relevant in this case.

# Dc.10. Is it explained in the Javadoc comment for each mutable field in a

thread-safe class that is neither volatile nor annotated with @GuardedBy, why that is safe?

Perhaps, the field is only accessed and mutated from a single method or a set of methods that are

specified to be called only from a single thread sequentially (described as per

Dc.1). This recommendation also applies to final fields that store objects of

non-thread-safe classes when those objects could be mutated from some methods of the enclosing

thread-safe class. See IS.2, IS.3,

RC.2, RC.3, and

RC.4 about what could go wrong with such code.

# IS.1. Can non-private static methods be called concurrently from multiple

threads? If there is a non-private static field with mutable state, such as a collection, is it an

instance of a thread-safe class or synchronized using some Collections.synchronizedXxx() method?

Note that calls to DateFormat.parse() and format() must be synchronized because they mutate the

object: see IS.5.

# IS.2. There is no situation where some thread awaits until a

non-volatile field has a certain value in a loop, expecting it to be updated from another thread?

The field should at least be volatile to ensure eventual visibility of concurrent updates. See

[JCIP 3.1, 3.1.4], and VNA00-J

for more details and examples.

Even if the respective field is volatile, busy waiting for a condition in a loop can be abused

easily and therefore should be justified in a comment: see NB.4.

Dc.10 also demands adding explaining comments to mutable fields which are neither

volatile nor annotated with @GuardedBy which should inevitably lead to the discovery of the

visibility issue.

# IS.3. Read accesses to non-volatile primitive fields which can be

updated concurrently are protected with a lock as well as the writes? The minimum reason for this

is that reads of long and double fields are non-atomic (see JLS 17.7, [JCIP 3.1.2], VNA05-J).

But even with other types of fields, unbalanced synchronization creates possibilities for downstream

bugs related to the visibility (see the previous item) and the lack of the expected happens-before

relationships.

As well as with the previous item, accurate documentation of benign races (Dc.8 and Dc.10) should reliably expose the cases when unbalanced synchronization is problematic.

See also RC.2 regarding unbalanced synchronization of read accesses to mutable objects, such as collections.

There is a relevant inspection "Field accessed in both synchronized and unsynchronized contexts" in IntelliJ IDEA.

# IS.4. Is the business logic written for server frameworks thread-safe? This includes:

Servlet implementations@(Rest)Controller-annotated classes, @Get/PostMapping-annotated methods in Spring@SessionScoped and @ApplicationScoped managed beans in JSFFilter and Handler implementations in various synchronous and asynchronous frameworks

(including Jetty, Netty, Undertow)@GET- and @POST-annotated methods (resources) in JAX-RS (RESTful APIs)It's easy to forget that if such code mutates some state (e. g. fields in the class), it must be properly synchronized or access only concurrent collections and classes.

# IS.5. Calls to parse() and format() on a shared instance of DateFormat are

synchronized, e. g. if a DateFormat is stored in a static field? Although parse() and

format() may look "read-only", they actually mutate the receiving DateFormat object.

An inspection "Non thread-safe static field access" in IntelliJ IDEA helps to catch such concurrency bugs.

# ETS.1. An example of excessive thread safety is a class where every modifiable

field is volatile or an AtomicReference or other atomic, and every collection field stores a

concurrent collection (e. g. ConcurrentHashMap), although all accesses to those fields are

synchronized.

There shouldn’t be any "extra" thread safety in code, there should be just enough of it. Duplication of thread safety confuses readers because they might think the extra thread safety precautions are (or used to be) needed for something but will fail to find the purpose.

The exception from this principle is the volatile modifier on the lazily initialized field in the

safe local double-checked locking pattern

which is the recommended way to implement double-checked locking, despite that volatile is

excessive for correctness

when the lazily initialized object has all final fields*. Without that

volatile modifier the thread safety of the double-checked locking could easily be broken by a

change (addition of a non-final field) in the class of lazily initialized objects, though that class

should not be aware of subtle concurrency implications. If the class of lazily initialized objects

is specified to be immutable (see Dc.3) the volatile is still

unnecessary and the UnsafeLocalDCL

pattern could be used safely, but the fact that some class has all final fields doesn’t

necessarily mean that it’s immutable.

See also the section about double-checked locking.

# ETS.2. Aren’t there AtomicReference, AtomicBoolean, AtomicInteger or

AtomicLong fields on which only get() and set() methods are called? Simple fields with

volatile modifiers can be used instead, but volatile might not be needed too; see

Dc.9.

# ETS.3. Does a class (method) need to be thread-safe? May a class be accessed (method called) concurrently from multiple threads (without happens-before relationships between the accesses or calls)? Can a class (method) be simplified by making it non-thread-safe?

See also Ft.1 about unneeded wrapping of a computation into a Future and

Dc.9 about potentially unneeded volatile modifiers.

This item is a close relative of Dn.1 (about rationalizing concurrency and thread safety in the patch description) and Dc.1 (about justifying concurrency in Javadocs for classes and methods, and documenting concurrent access). If these actions are done, it should be self-evident whether the class (method) needs to be thread-safe or not. There may be cases, however, when it might be desirable to make the class (method) thread-safe although it's not supposed to be accessed or called concurrently as of the moment of the patch. For example, thread safety may be needed to ensure memory safety (see CN.4 about this). Anticipating some changes to the codebase that make the class (method) being accessed from multiple threads may be another reason to make the class (method) thread-safe up front.

# ETS.4. Does a ReentrantLock (or ReentrantReadWriteLock, Semaphore)

need to be fair? To justify the throughput penalty of making a lock fair it should be demonstrated

that a lack of fairness leads to unacceptably long starvation periods in some threads trying to

acquire the lock or pass the semaphore. This should be documented in the Javadoc comment for the

field holding the lock or the semaphore. See [JCIP 13.3] for more details.

# RC.1. Aren’t ConcurrentMap (or Cache) objects updated with separate

containsKey(), get(), put() and remove() calls instead of a single call to

compute()/computeIfAbsent()/computeIfPresent()/replace()?

# RC.2. Aren’t there point read accesses such as Map.get(),

containsKey() or List.get() outside of critical sections to a non-thread-safe collection such as

HashMap or ArrayList, while new entries can be added to the collection concurrently, even

though there is a happens-before edge between the moment when some entry is put into the collection

and the moment when the same entry is point-queried outside of a critical section?

The problem is that when new entries can be added to a collection, it grows and changes its internal

structure from time to time (HashMap rehashes the hash table, ArrayList reallocates the internal

array). At such moments races might happen and unprotected point read accesses might fail with

NullPointerException, ArrayIndexOutOfBoundsException, or return null or some random entry.

Note that this concern applies to ArrayList even when elements are only added to the end of the

list. However, a small change in ArrayList’s implementation in OpenJDK could have disallowed data

races in such cases at very little cost. If you are subscribed to the concurrency-interest mailing

list, you could help to bring attention to this problem by reviving this thread.

See also IS.3 regarding unbalanced synchronization of accesses to primitive fields.

# RC.3. A variation of the previous item: isn’t a non-thread-safe

collection such as HashMap or ArrayList iterated outside of a critical section, while it may

be modified concurrently? This could happen by accident when an Iterable, Iterator or Stream

over a collection is returned from a method of a thread-safe class, even though the iterator or

stream is created within a critical section. Note that returning unmodifiable collection views

like Collections.unmodifiableList() from getters wrapping collection fields that may be modified

concurrently doesn't solve this problem. If the collection is relatively small, it should be

copied entirely, or a copy-on-write collection (see Sc.3) should be

used instead of a non-thread-safe collection.

Note that calling toString() on a collection (e. g. in a logging statement) implicitly iterates

over it.

Like the previous item, this one applies to growing ArrayLists too.

This item applies even to synchronized collections: see RC.10 for details.

# RC.4. Generalization of the previous item: aren’t non-trivial objects that can be mutated concurrently returned from getters in a thread-safe class (and thus inevitably leaking outside of critical sections)?

# RC.5. If there are multiple variables in a thread-safe class that are

updated at once but have individual getters, isn’t there a race condition in the code that calls

those getters? If there is, the variables should be made final fields in a dedicated POJO, that

serves as a snapshot of the updated state. The POJO is stored in a field of the thread-safe class,

directly or as an AtomicReference. Multiple getters to individual fields should be replaced with

a single getter that returns the POJO. This allows avoiding a race condition in the client code by

reading a consistent snapshot of the state at once.

This pattern is also very useful for creating safe and reasonably simple non-blocking code: see NB.2 and [JCIP 15.3.1].

# RC.6. If some logic within some critical section depends on some data that principally is part of the internal mutable state of the class, but was read outside of the critical section or in a different critical section, isn’t there a race condition because the local copy of the data may become out of sync with the internal state by the time when the critical section is entered? This is a typical variant of check-then-act race condition, see [JCIP 2.2.1].

An example of this race condition is calling toArray() on synchronized collections with a sized

array:

list = Collections.synchronizedList(new ArrayList<>());

...

elements = list.toArray(new Element[list.size()]);

This might unexpectedly leave the elements array with some nulls in the end if there are some

concurrent removals from the list. Therefore, toArray() on a synchronized collection should be

called with a zero-length array: toArray(new Element[0]), which is also not worse from the

performance perspective: see "Arrays of Wisdom of the

Ancients".

See also RC.9 about cache invalidation races which are similar to check-then-act races.

# RC.7. Aren't there race conditions between the code (i. e. program runtime actions) and some actions in the outside world or actions performed by some other programs running on the machine? For example, if some configurations or credentials are hot reloaded from some file or external registry, reading separate configuration parameters or separate credentials (such as username and password) in separate transactions with the file or the registry may be racing with a system operator updating those configurations or credentials.

Another example is checking that a file exists (or not exists) and then reading, deleting, or

creating it, respectively, while another program or a user may delete or create the file between the

check and the act. It's not always possible to cope with such race conditions, but it's useful to

keep such possibilities in mind. Prefer static methods from java.nio.file.Files class and

NIO file reading/writing API to methods from the old java.io.File for file system operations.

Methods from Files are more sensitive to file system race conditions and tend to throw exceptions

in adverse cases, while methods on File swallow errors and make it hard even to detect race

conditions. Static methods from Files also support StandardOpenOption.CREATE and CREATE_NEW

which may help to ensure some extra atomicity.

# RC.8. If you are using Guava Cache and invalidate(key), are

you not affected by the race condition which can

leave a Cache with an invalid (stale) value mapped for a key? Consider using Caffeine cache which doesn't have this problem. Caffeine is also faster and

more scalable than Guava Cache: see Sc.9.

# RC.9. Generalization of the previous item: isn't there a potential cache invalidation race in the code? There are several ways to get into this problem:

Cache.put() method concurrently with invalidate(). Unlike

RC.8, this is a race regardless of what caching library is used,

not necessarily Guava. This is also similar to RC.1.put() and invalidate() methods exposed in the own Cache interface. This places the

burden of synchronizing put() (together the preceding "checking" code, such as get()) and

invalidate() calls on the users of the API which really should be the job of the Cache

implementation.

# RC.10. The whole iteration loop over a synchronized collection

(i. e. obtained from one of the Collections.synchronizedXxx() static factory methods), or a

Stream pipeline using a synchronized collection as a source is protected by synchronized (coll)?

See the Javadoc

for examples and details.

This also applies to passing synchronized collections into:

new ArrayList<>(synchronizedColl)List.copyOf(), Set.copyOf(),

ImmutableMap.copyOf()otherColl.containsAll(synchronizedColl)otherColl.addAll(synchronizedColl)otherColl.removeAll(synchronizedColl)otherMap.putAll(synchronizedMap)otherColl.containsAll(synchronizedMap.keySet())Because in all these cases there is an implicit iteration on the source collection.

See also RC.3 about unprotected iteration over non-thread-safe collections.

# T.1. Was it considered to add multi-threaded unit tests for a thread-safe class or method? Single-threaded tests don't really test the thread safety and concurrency. Note that this question doesn't mean to indicate that there must be concurrent unit tests for every piece of concurrent code in the project because correct concurrent tests take a lot of effort to write and therefore they might often have low ROI.

What is the worst thing that might happen if this code has a concurrency bug? This is a useful question to inform the decision about writing concurrent tests. The consequences may range from a tiny, entirely undetectable memory leak, to storing corrupted data in a durable database or a security breach.

# T.2. Isn't a shared java.util.Random object used for data

generation in a concurrency test? java.util.Random is synchronized internally, so if multiple

test threads (which are conceived to access the tested class concurrently) access the same

java.util.Random object then the test might degenerate to a mostly synchronous one and fail to

exercise the concurrency properties of the tested class. See [JCIP 12.1.3]. Math.random() is a

subject for this problem too because internally Math.random() uses a globally shared

java.util.Random instance. Use ThreadLocalRandom instead.

# T.3. Do concurrent test workers coordinate their start using a latch

such as CountDownLatch? If they don't much or even all of the test work might be done by the

first few started workers. See [JCIP 12.1.3] for more information.

# T.4. Are there more test threads than there are available

processors if possible for the test? This will help to generate more thread scheduling

interleavings and thus test the logic for the absence of race conditions more thoroughly. See

[JCIP 12.1.6] for more information. The number of available processors on the machine can be

obtained as Runtime.getRuntime().availableProcessors().

# T.5. Are there no regular assertions in code that is executed not in the main thread running the unit test? Consider the following example:

@Test public void testServiceListener() {

// Missed assertion -- Don't do this!

service.addListener(event -> Assert.assertEquals(Event.Type.MESSAGE_RECEIVED, event.getType()));

service.sendMessage("test");

}

Assuming the service executes the code of listeners asynchronously in some internally-managed or

a shared thread pool, even if the assertion within the listener's lambda fails, JUnit and TestNG

will think the test has passed.

The solution to this problem is either to pass the data (or thrown exceptions) from a concurrent thread back to the main test thread and verify it in the end of the test, or to use ConcurrentUnit library which takes over the boilerplate associated with the first approach.

# T.6. Is the result of CountDownLatch.await()

method calls checked? The most frequent form of this mistake is forgetting to wrap

CountDownLatch.await() into assertTrue() in tests, which makes the test to not actually verify

that the production code works correctly. The absence of a check in production code might cause

race conditions.

Apart from CountDownLatch.await, the other similar methods whose result must be checked are:

Lock.tryLock()

and tryAcquire() methods on Semaphore

and RateLimiter

from GuavaMonitor.enter(...) in GuavaCondition.await(...)awaitTermination() and awaitQuiescence() methods. There is a separate

item about them.Process.waitFor(...)It's possible to find these problems using static analysis, e. g. by configuring the "Result of

method call ignored" inspection in IntelliJ IDEA to recognize Lock.tryLock(),

CountDownLatch.await() and other methods listed above. They are not in the default set of

checked methods, so they should be added manually in the inspection configuration.

# Lk.1. Is it possible to use concurrent collections and/or utilities from

java.util.concurrent.* and avoid using locks with Object.wait()/notify()/notifyAll()?

Code redesigned around concurrent collections and utilities is often both clearer and less

error-prone than code implementing the equivalent logic with intrinsic locks, Object.wait() and

notify() (Lock objects with await() and signal() are not different in this regard). See

[EJ Item 81] for more information.

# Lk.2. Is it possible to simplify code that uses intrinsic locks or Lock

objects with conditional waits by using Guava’s Monitor

instead?

# Lk.3. Isn't ReentrantLock used when synchronized would suffice?

ReentrantLock shoulndn't be used in the situations when none of its distinctive features

(tryLock(), timed and interruptible locking methods, etc.) are used. Note that reentrancy is not

such a feature: intrinsic Java locks support reentrancy too. The ability for a ReentrantLock to be

fair is seldom such a feature: see ETS.4. See [JCIP 13.4] for more information

about this.

This advice also applies when a class uses a private lock object (instead of synchronized (this)

or synchronized methods) to protect against accidental or malicious interference by the clients

acquiring synchronizing on the object of the class: see [JCIP 4.2.1], [EJ Item 82], LCK00-J.

# Lk.4. Locking (lock(), lockInterruptibly(), tryLock()) and unlock()

methods are used strictly with the recommended try-finally idiom

without deviations?

lock() (or lockInterruptibly()) call goes before the try {} block rather than within it?lock() (or lockInterruptibly()) call and the beginning of

the try {} block?unlock() call is the first statement within the finally {} block?This advice doesn't apply when locking methods and unlock() should occur in different scopes, i.

e. not within the recommended try-finally idiom altogether. The containing methods could be

annotated with Error Prone's @LockMethod and

@UnlockMethod annotations.

There is a "Lock acquired but not safely unlocked" inspection in IntelliJ IDEA which corresponds to this item.

See also LCK08-J.

# Dl.1. If a thread-safe class is implemented so that there are nested critical sections protected by different locks, is it possible to redesign the code to get rid of nested critical sections? Sometimes a class could be split into several distinct classes, or some work that is done within a single thread could be split between several threads or tasks which communicate via concurrent queues. See [JCIP 5.3] for more information about the producer-consumer pattern.

There is an inspection "Nested 'synchronized' statement" in IntelliJ IDEA corresponding to this item.

# Dl.2. If restructuring a thread-safe class to avoid nested critical sections is not reasonable, was it deliberately checked that the locks are acquired in the same order throughout the code of the class? Is the locking order documented in the Javadoc comments for the fields where the lock objects are stored?

See LCK07-J for examples.

# Dl.3. If there are nested critical sections protected by several (potentially different) dynamically determined locks (for example, associated with some business logic entities), are the locks ordered before the acquisition? See [JCIP 10.1.2] for more information.

# Dl.4. Aren’t there calls to some callbacks (listeners, etc.) that can be configured through public API or extension interface calls within critical sections? With such calls, the system might be inherently prone to deadlocks because the external logic executed within a critical section may be unaware of the locking considerations and call back into the logic of the system, where some more locks may be acquired, potentially forming a locking cycle that might lead to a deadlock. Also, the external logic could just perform some time-consuming operation and by that harm the efficiency of the system (see Sc.1). See [JCIP 10.1.3] and [EJ Item 79] for more information.

When public API or extension interface calls happen within lambdas passed into Map.compute(),

computeIfAbsent(), computeIfPresent(), and merge(), there is a risk of not only deadlocks (see

the next item) but also race conditions which could result in a corrupted map (if it's not a

ConcurrentHashMap, e. g. a simple HashMap) or runtime exceptions.

Beware that a CompletableFuture or a ListenableFuture returned from a public API opens a door for performing some user-defined callbacks from the place

where the future is completed, deep inside the library (framework). If the future is completed

within a critical section, or from an ExecutorService whose threads must not block, such as a

ForkJoinPool (see TE.4) or the worker pool of an I/O library, consider either

returning a simple Future, or documenting that stages shouldn't be attached to this

CompletableFuture in the default execution mode. See TE.7 for more

information.

# Dl.5. Aren't there calls to methods on a ConcurrentHashMap instance

within lambdas passed into compute()-like methods called on the same map? For example, the

following code is deadlock-prone:

map.compute(key, (String k, Integer v) -> {

if (v == null || v == 0) {

return map.get(DEFAULT_KEY);

}

return v;

});

Note that nested calls to non-lambda accepting methods, including read-only access methods like

get() create the possibility of deadlocks as well as nested calls to compute()-like methods

because the former are not always lock-free.

# Sc.1. Are critical sections as small as possible? For every critical section: can’t some statements in the beginning and the end of the section be moved out of it? Not only minimizing critical sections improves scalability, but also makes it easier to review them and spot race conditions and deadlocks.

This advice equally applies to lambdas passed into ConcurrentHashMap’s compute()-like methods.

See also [JCIP 11.4.1] and [EJ Item 79].

# Sc.2. Is it possible to increase locking granularity? If a

thread-safe class encapsulates accesses to map, is it possible to turn critical sections into

lambdas passed into ConcurrentHashMap.compute() or computeIfAbsent() or computeIfPresent()

methods to enjoy effective per-key locking granularity? Otherwise, is it possible to use

Guava’s Striped or an equivalent? See

[JCIP 11.4.3] for more information about lock striping.

# Sc.3. Is it possible to use non-blocking collections instead of blocking ones? Here are some possible replacements within JDK:

Collections.synchronizedMap(HashMap), Hashtable → ConcurrentHashMapCollections.synchronizedSet(HashSet) → ConcurrentHashMap.newKeySet()Collections.synchronizedMap(TreeMap) → ConcurrentSkipListMap. By the way,

ConcurrentSkipListMap is not the state of the art concurrent sorted dictionary implementation.

SnapTree is more efficient than ConcurrentSkipListMap and there have

been some research papers presenting algorithms that are claimed to be more efficient than

SnapTree.Collections.synchronizedSet(TreeSet) → ConcurrentSkipListSetCollections.synchronizedList(ArrayList), Vector → CopyOnWriteArrayListLinkedBlockingQueue → ConcurrentLinkedQueueLinkedBlockingDeque → ConcurrentLinkedDequeConsider also using queues from JCTools instead of concurrent queues from the JDK: see Sc.8.

See also an item about using ForkJoinPool instead of newFixedThreadPool(N)

for high-traffic executor services, which internally amounts to replacing a single blocking queue of

tasks inside ThreadPoolExecutor with multiple non-blocking queues inside ForkJoinPool.

# Sc.4. Is it possible to use ClassValue instead of

ConcurrentHashMap<Class, ...>? Note, however, that unlike ConcurrentHashMap with its

computeIfAbsent() method ClassValue doesn’t guarantee that per-class value is computed only

once, i. e. ClassValue.computeValue() might be executed by multiple concurrent threads. So if the

computation inside computeValue() is not thread-safe, it should be synchronized separately. On the

other hand, ClassValue does guarantee that the same value is always returned from

ClassValue.get() (unless remove() is called).

# Sc.5. Was it considered to replace a simple lock with a ReadWriteLock?

Beware, however, that it’s more expensive to acquire and release a ReentrantReadWriteLock than a

simple intrinsic lock, so the increase in scalability comes at the cost of reduced throughput. If

the operations to be performed under a lock are short, or if a lock is already striped (see

Sc.2) and therefore very lightly contended, replacing a simple

lock with a ReadWriteLock might have a net negative effect on the application performance. See

this comment

for more details.

# Sc.6. Is it possible to use a StampedLock

instead of a ReentrantReadWriteLock when reentrancy is not needed?

# Sc.7. Is it possible to use LongAdder

for "hot fields" (see [JCIP 11.4.4]) instead of AtomicLong or AtomicInteger on which only

methods like incrementAndGet(), decrementAndGet(), addAndGet() and (rarely) get() is called,

but not set() and compareAndSet()?

Note that a field should be really updated from several concurrent threads steadily to justify using

LongAdder. If the field is usually updated only from one thread at a time (there may be several

updating threads, but each of them accesses the field infrequently, so the updates from different

threads rarely happen at the same time) it's still better to use AtomicLong or AtomicInteger

because they take less memory than LongAdder and their updates are cheaper.

# Sc.8. Was it considered to use one of the array-based queues from the JCTools

library instead of ArrayBlockingQueue?

Those queues from JCTools are classified as blocking, but they avoid lock acquisition in many cases

and are generally much faster than ArrayBlockingQueue.

See also Sc.3 regarding replacing blocking queues (and other collections) with non-blocking equivalents within JDK.

# Sc.9. Was it considered to use Caffeine cache instead of other Cache implementations (such from Guava)? Caffeine's performance is very good compared to other caching libraries.

Another reason to use Caffeine instead of Guava Cache is that it avoids an invalidation race: see RC.8.

# Sc.10. When some state or a condition is checked, or resource is allocated within

a critical section, and the result is usually expected to be positive (access granted,

resource allocated) because the entity is rarely in a protected, restricted, or otherwise special

state, or because the underlying resource is rarely in shortage, is it possible to apply

speculation (optimistic concurrency) to improve scalability? This means to use lighter-weight

synchronization (e. g. shared locking with a ReadWriteLock or a StampedLock instead of exclusive

locking) sufficient just to detect a shortage of the resource or that the entity is in a special

state, and fallback to heavier synchronization only when necessary.

This principle is used internally in many scalable concurrent data structures, including

ConcurrentHashMap and JCTools's queues, but could be applied on the higher logical level as well.

See also the article about Optimistic concurrency control on Wikipedia.

# Sc.11. Was it considered to use a ForkJoinPool instead of a

ThreadPoolExecutor with N threads (e. g. returned from one of Executors.newFixedThreadPool()

methods), for thread pools on which a lot of small tasks are executed? ForkJoinPool is more

scalable because internally it maintains one queue per each worker thread, whereas

ThreadPoolExecutor has a single, blocking task queue shared among all threads.

ForkJoinPool implements ExecutorService as well as ThreadPoolExecutor, so could often be a

drop in replacement. For caveats and details, see this and this messages by Doug Lea.

See also items about using non-blocking collections (including queues) instead of blocking ones and about using JCTools queues.

Regarding all items in this section, see also [EJ Item 83] and "Safe Publication this and Safe Initialization in Java".

# LI.1. For every lazily initialized field: is the initialization code thread-safe and might it be called from multiple threads concurrently? If the answers are "no" and "yes", either double-checked locking should be used or the initialization should be eager.

Be especially wary of using lazy-initialization in mutable objects. They are prone to cache invalidation race conditions: see RC.9.

# LI.2. If a field is initialized lazily under a simple lock, is it possible to use double-checked locking instead to improve performance?

# LI.3. Does double-checked locking follow the SafeLocalDCL pattern, as noted in ETS.1?

If the initialized objects are immutable a more efficient UnsafeLocalDCL

pattern might also be used. However, if the lazily-initialized field is not volatile and there are

accesses to the field that bypass the initialization path, the value of the field must be

carefully cached in a local variable. For example, the following code is buggy:

private MyImmutableClass lazilyInitializedField;

void doSomething() {

...

if (lazilyInitializedField != null) { // (1)

lazilyInitializedField.doSomethingElse(); // (2) - Can throw NPE!

}

}

This code might result in a NullPointerException, because although a non-null value is observed

when the field is read the first time at line 1, the second read at line 2 could observe null.

The above code could be fixed as follows:

void doSomething() {

MyImmutableClass lazilyInitialized = this.lazilyInitializedField;

if (lazilyInitialized != null) {

// Calling doSomethingElse() on a local variable to avoid NPE:

// see https://github.com/code-review-checklists/java-concurrency#safe-local-dcl

lazilyInitialized.doSomethingElse();

}

}

See "Wishful Thinking: Happens-Before Is The Actual Ordering" and "Date-Race-Ful Lazy Initialization for Performance" for more information.

# LI.4. In each particular case, doesn’t the net impact of double-checked locking and lazy field initialization on performance and complexity overweight the benefits of lazy initialization? Isn’t it ultimately better to initialize the field eagerly?

# LI.5. If a field is initialized lazily under a simple lock or using

double-checked locking, does it really need locking? If nothing bad may happen if two threads do the

initialization at the same time and use different copies of the initialized state then a benign race

could be allowed. The initialized field should still be volatile (unless the initialized objects

are immutable) to ensure there is a happens-before edge between threads doing the initialization and

reading the field. This is called a single-check idiom (or a racy single-check idiom if the

field doesn't have a volatile modifier) in [EJ Item 83].

Annotate such fields with @LazyInit from

error_prone_annotations. The place

in code with the race should also be identified with WARNING comments: see

NB.3.

# LI.6. Is lazy initialization holder class idiom used for static fields which must be lazy rather than double-checked locking? There are no reasons to use double-checked locking for static fields because lazy initialization holder class idiom is simpler, harder to make mistake in, and is at least as efficient as double-checked locking (see benchmark results in "Safe Publication and Safe Initialization in Java").

# NB.1. If there is some non-blocking or semi-symmetrically blocking code that mutates the state of a thread-safe class, was it deliberately checked that if a thread on a non-blocking mutation path is preempted after each statement, the object is still in a valid state? Are there enough comments, perhaps before almost every statement where the state is changed, to make it relatively easy for readers of the code to repeat and verify the check?

# NB.2. Is it possible to simplify some non-blocking code by confining

all mutable state in an immutable POJO and update it via compare-and-swap operations? This pattern

is also mentioned in RC.5. Instead of a POJO, a single long value could be

used if all parts of the state are integers that can together fit 64 bits. See also [JCIP 15.3.1].

# NB.3. Are there visible WARNING comments identifying the boundaries of non-blocking code? The comments should mark the start and the end of non-blocking code, partially blocking code, and benignly racy code (see Dc.8 and LI.5). The opening comments should:

# NB.4. If some condition is awaited in a (busy) loop, like in the following example:

volatile boolean condition;

// in some method:

while (!condition) {

// Or Thread.sleep/yield/onSpinWait, or no statement, i. e. a pure spin wait

TimeUnit.SECONDS.sleep(1L);

}

// ... do something when condition is true

Is it explained in a comment why busy waiting is needed in the specific case, and why the costs and potential problems associated with busy waiting (see [JCIP 12.4.2] and [JCIP 14.1.1]) either don't apply in the specific case or are outweighed by the benefits?

If there is no good reason for spin waiting, it's preferable to synchronize explicitly using a tool

such as Semaphore,

CountDownLatch, or Exchanger,

or if the logic for which the spin loop awaits is executed in some ExecutorService, it's better to

add a callback to the corresponding CompletableFuture or ListenableFuture (check TE.7

about doing this properly).

In test code waiting for some condition, a library such as Awaitility could be used instead of explicit looping with

Thread.sleep calls.

Since Thread.yield() and Thread.onSpinWait() are rarely, if ever, useful outside of spin loops,

this item could also be interpreted as that there should be a comment to every call to either of

these methods, explaining either why they are called outside of a spin loop, or justifying the spin

loop itself.

In any case, the field checked in the busy loop must be volatile: see

IS.2 for details.

The busy wait pattern is covered by IntelliJ IDEA's inspections "Busy wait" and "while loop spins on field".

# TE.1. Are Threads given names when created? Are ExecutorServices created with thread factories that name threads?

It appears that different projects have different policies regarding other aspects of Thread

creation: whether to make them daemon with setDaemon(), whether to set thread priorities and

whether a ThreadGroup should be specified. Many of such rules can be effectively enforced with

forbidden-apis.

# TE.2. Aren’t there threads created and started, but not stored in fields, a-la

new Thread(...).start(), in some methods that may be called repeatedly? Is it possible to

delegate the work to a cached or a shared ExecutorService instead?

Another form of this problem is when a Thread (or an ExecutorService) is created and managed

within objects (in other words, active objects) that

are relatively short-lived. Is it possible to reuse executors by creating them one level up the

stack and passing shared executors to constructors of the short-lived objects, or a shared

ExecutorService stored in a static field?

# TE.3. Aren’t some network I/O operations performed in an

Executors.newCachedThreadPool()-created ExecutorService? If a machine that runs the

application has network problems or the network bandwidth is exhausted due to increased load,

CachedThreadPools that perform network I/O might begin to create new threads uncontrollably.

Note that completing some CompletableFuture or SettableFuture from inside a cached thread pool

and then returning this future to a user might expose the thread pool to executing unwanted actions

if the future is used improperly: see TE.7 for details.

# TE.4. Aren’t there blocking or I/O operations performed in tasks scheduled

to a ForkJoinPool (except those performed via a managedBlock() call)? Parallel Stream operations are executed in the common ForkJoinPool implicitly, as well

as the lambdas passed into CompletableFuture’s methods whose names end with "Async" but not

accepting a custom executor.

Note that attaching blocking or I/O operations to a CompletableFuture as stage in default

execution mode (via methods like thenAccept(), thenApply(), handle(), etc.) might also

inadvertently lead to performing them in ForkJoinPool from where the future may be completed: see

TE.7.

Thread.sleep() is a blocking operation.

This advice should not be taken too far: occasional transient IO (such as that may happen during

logging) and operations that may rarely block (such as ConcurrentHashMap.put() calls) usually

shouldn’t disqualify all their callers from execution in a ForkJoinPool or in a parallel Stream.

See Parallel Stream Guidance for the

more detailed discussion of these tradeoffs.

See also the section about parallel Streams.

# TE.5. An opposite of the previous item: can non-blocking computations be

parallelized or executed asynchronously by submitting tasks to ForkJoinPool.commonPool() or via

parallel Streams instead of using a custom thread pool (e. g. created by one of the static factory

methods from ExecutorServices)? Unless the custom thread pool is configured with a ThreadFactory

that specifies a non-default priority for threads or a custom exception handler (see

TE.1) there is little reason to create more threads in the system instead of

reusing threads of the common ForkJoinPool.

# TE.6. Is every ExecutorService treated as a resource and is shut down

explicitly in the close() method of the containing object, or in a try-with-resources of a

try-finally statement? Failure to shutdown an ExecutorService might lead to a thread leak even if

an ExecutorService object is no longer accessible, because some implementations (such as

ThreadPoolExecutor) shutdown themselves in a finalizer, while finalize() is not guaranteed to

ever be called by

the JVM.

To make explicit shutdown possible, first, ExecutorService objects must not be assinged into

variables and fields of Executor type.

# TE.7. Are non-async stages attached to a CompletableFuture simple and

non-blocking unless the future is completed from a thread in the same thread pool as the thread from where a CompletionStage is attached?

This also applies when asynchronous callback is attached using Guava's

ListenableFuture.addListener() or Futures.addCallback() methods and directExecutor() (or an equivalent) is provided as the executor for the callback.

Non-async execution is called default execution (or default mode) in the documentation for

CompletionStage:

these are methods thenApply(), thenAccept(), thenRun(), handle(), etc. Such stages may be

executed either from the thread adding a stage, or from the thread calling future.complete().

If the CompletableFuture originates from a library, it's usually unknown in which thread

(executor) it is completed, therefore, chaining a heavyweight, blocking, or I/O operation to such a

future might lead to problems described in TE.3,

TE.4 (if the future is completed from a ForkJoinPool or an event loop executor

in an asynchronous library), and Dl.4.

Even if the CompletableFuture is created in the same codebase as stages attached to it, but is

completed in a different thread pool, default stage execution mode leads to non-deterministic

scheduling of operations. If these operations are heavyweight and/or blocking, this reduces the

system's operational predictability and robustness, and also creates a subtle dependency between the

components: e. g. if the component which completes the future decides to migrate this action to a

ForkJoinPool, it could suddenly lead to the problems described in the previous paragraph.

A lightweight, non-blocking operation which is OK to attach to a CompletableFuture as a non-async

stage may be something like incrementing an AtomicInteger counter, adding an element to a

non-blocking queue, putting a value into a ConcurentHashMap, or a logging statement.

It's also fine to attach a stage in the default mode if preceded with if (future.isDone()) check

which guarantees that the completion stage will be executed immediately in the current thread

(assuming the current thread belongs to the proper thread pool to perform the stage action).

The specific reason(s) making non-async stage or callback attachment permissible (future completion

and stage attachment happening in the same thread pool; simple/non-blocking callback; or

future.isDone() check) should be identified in a comment.

See also the Javadoc for ListenableFuture.addListener() describing this problem.

# TE.8. Is it possible to execute a task or an action with a delay via a

ScheduledExecutorService

rather than by calling Thread.sleep() before performing the work or submitting the task to

an executor? ScheduledExecutorService allows to execute many such tasks on a small number of

threads, while the approach with Thread.sleep requires a dedicated thread for every delayed

action. Sleeping in the context of an unknown executor (if there is insufficient concurrent access

documentation for the method, as per Dc.1, or if this is a

concurrency-agnostic library method) before submitting the task to an executor is also bad: the

context executor may not be well-suited for blocking calls such as Thread.sleep, see

TE.4 for details.

This item equally applies to scheduling one-shot and recurrent delayed actions, there are methods

for both scenarios in ScheduledExecutorService.

Be cautious, however, about scheduling tasks with affinity to system time or UTC time (e. g.

beginning of each hour) using ScheduledThreadPoolExecutor: it can experience unbounded clock

drift.

# TE.9. The result of ExecutorService.awaitTermination() method

calls is checked? Calling awaitTermination() (or ForkJoinPool.awaitQuiescence()) and not

checking the result makes little sense. If it's actually important to await termination, e. g. to

ensure a happens-before relation between the completion of the actions scheduled to the

ExecutorService and some actions following the awaitTermination() call, or because termination

means a release of some heavy resource and if the resource is not released there is a noticeable

leak, then it is reasonable to at least check the result of awaitTermination() and log a warning

if the result is negative, making debugging potential problems in the future easier. Otherwise, if

awaiting termination really makes no difference, then it's better to not call awaitTermination()

at all.

Apart from ExecutorService, this item also applies to awaitTermination() methods on

AsynchronousChannelGroup

and io.grpc.ManagedChannel

from gRPC-Java.

It's possible to find omitted checks for awaitTermination() results using Structural search

inspection in

IntelliJ IDEA with the following pattern:

$x$.awaitTermination($y$, $z$);

See also a similar item about not checking the result of CountDownLatch.await().

# TE.10. Isn't ExecutorService assigned into a variable or a

field of Executor type? This makes it impossible to follow the practice of explicit shutdown of

ExecutorService objects.

In IntelliJ IDEA, it's possible to find violations of this practice automatically using two patterns added to Structural Search inspection:

$x$ = $y$, where the "Type" of $x$ is Executor ("within type hierarchy"

flag is off) and the "Type" of $y$ is ExecutorService ("within type hierarchy" flag is on).$Type$ $x$ = $y$;, where the "Text" of $Type$ is Executor

and the "Type" of $y$ is ExecutorService (within type hierarchy).

# TE.11. Isn't ScheduledExecutorService assigned into

a variable or a field of ExecutorService type? This is wasteful because the primary Java

implementation of ScheduledExecutorService, ScheduledThreadPoolExecutor

(it is returned from Executors.newScheduledThreadPool() and newSingleThreadScheduledExecutor()

static factory methods) uses a PriorityQueue internally to manage tasks which incurs higher memory

footprint and CPU overhead compared to non-scheduled ExecutorService implementations such as

vanilla ThreadPoolExecutor or ForkJoinPool.

This problem could be caught statically in a way similar to what is described in the previous item.

# PS.1. For every use of parallel Streams via

Collection.parallelStream() or Stream.parallel(): is it explained why parallel Stream is

used in a comment preceding the stream operation? Are there back-of-the-envelope calculations or

references to benchmarks showing that the total CPU time cost of the parallelized computation

exceeds 100 microseconds?

Is there a note in the comment that parallelized operations are generally I/O-free and non-blocking,

as per TE.4? The latter might be obvious momentary, but as codebase evolves the

logic that is called from the parallel stream operation might become blocking accidentally. Without

comment, it’s harder to notice the discrepancy and the fact that the computation is no longer a good

fit for parallel Streams. It can be fixed by calling the non-blocking version of the logic again or

by using a simple sequential Stream instead of a parallel Stream.

# Ft.1. Does a method returning a Future do some blocking operation

asynchronously? If it doesn't, was it considered to perform non-blocking computation logic and

return the result directly from the method, rather than within a Future? There are situations

when someone might still want to return a Future wrapping some non-blocking computation,

essentially relieving the users from writing boilerplate code like

CompletableFuture.supplyAsync(obj::expensiveComputation) if all of them want to run the method

asynchronously. But if at least some of the clients don't need the indirection, it's better not to

wrap the logic into a Future prematurely and give the users of the API a choice to do this

themselves.

See also ETS.3 about unneeded thread-safety of a method.

# Ft.2. Aren't there blocking operations in a method returning a

Future before asynchronous execution is started, and is it started at all? Here is the

antipattern:

// DON'T DO THIS

Future<Salary> getSalary(Employee employee) throws ConnectionException {

Branch branch = retrieveBranch(employee); // A database or an RPC call

return CompletableFuture.supplyAsync(() -> {

return retrieveSalary(branch, employee); // Another database or an RPC call

}, someBlockingIoExecutor());

}

Blocking the caller thread is unexpected for a user seeing a method returning a Future.

An example completely without asynchrony:

// DON'T DO THIS

Future<Salary> getSalary(Employee employee) throws ConnectionException {

SalaryDTO salaryDto = retrieveSalary(employee); // A database or an RPC call

Salary salary = toSalary(salaryDto);

return completedFuture(salary); // Or Guava's immediateFuture(), Scala's successful()

}

If the retrieveSalary() method is not blocking itself, the getSalary() may not need to return

a Future.

Another problem with making blocking calls before scheduling an Future is that the resulting code

has multiple failure paths: either the future may complete

exceptionally, or the method itself may throw an exception (typically from the blocking operation),

which is illustrated by getSalary() throws ConnectionException in the above examples.

This advice also applies when a method returns any object representing an asynchronous execution

other than Future, such as Deferred, Flow.Publisher, org.reactivestreams.Publisher,

or RxJava's Observable.

# Ft.3. If a method returns a Future and some logic in the

beginning of it may lead to an expected failure (i. e. not a result of a programming bug), was

it considered to propagate an expected failure by a Future completed exceptionally, rather than

throwing from the method? For example, the following method:

Future<Response> makeQuery(String query) throws InvalidQueryException {

Request req = compile(query); // Can throw an InvalidQueryException

return CompletableFuture.supplyAsync(() -> service.remoteCall(req), someBlockingIoExecutor());

}

May be converted into:

Future<Response> makeQuery(String query) {

try {

Request req = compile(query);

} catch (InvalidQueryException e) {

// Explicit catch preserves the semantics of the original version of makeQuery() most closely.

// If compile(query) is an expensive computation, it may be undesirable to schedule it to

// someBlockingIoExecutor() by simply moving compile(query) into the lambda below because if

// this pool has more threads than CPUs then too many compilations might be started in parallel,

// leading to excessive switches between threads running CPU-bound tasks.

// Another alternative is scheduling compile(query) to the common FJP:

// CompletableFuture.supplyAsync(() -> compile(query))

// .thenApplyAsync(service::remoteCall, someBlockingIoExecutor());

CompletableFuture<Response> f = new CompletableFuture<>();

f.completeExceptionally(e);

return f; // Or use Guava's immediateFailedFuture()

}

return CompletableFuture.supplyAsync(() -> service.remoteCall(req), someBlockingIoExecutor());

}

The point of this refactoring is unification of failure paths, so that the users of the API don't have to deal with multiple different ways of handling errors from the method.

Similarly to the previous item, this consideration also applies when

a method returns any object representing an asynchronous execution other than Future, such as

Deferred, Publisher, or Observable.

Future cancellation

# IF.1. If some code propagates InterruptedException wrapped into another

exception (e. g. RuntimeException), is the interruption status of the current thread restored

before the wrapping exception is thrown?

Propagating InterruptedException wrapped into another exception is a controversial practice

(especially in libraries) and it may be prohibited in some projects completely, or in specific

subsystems.

# IF.2. If some method returns normally after catching an

InterruptedException, is this coherent with the (documented) semantics of the method? Returning

normally after catching an InterruptedException usually makes sense only in two types of methods:

Runnable.run() or Callable.call() themselves, or methods that are intended to be submitted as

tasks to some Executors as method references. Thread.currentThread().interrupt() should still be

called before returning from the method, assuming that the interruption policy of the threads in

the Executor is unknown.log() or sendMetric() could probably be such

methods, as well as boolean trySendMoney(), but not void sendMoney().If a method doesn’t fall into either of these categories, it should propagate InterruptedException

directly or wrapped into another exception (see the previous item), or it should not return normally

after catching an InterruptedException, but rather continue execution in some sort of retry loop,

saving the interruption status and restoring it before returning (see an example from JCIP). Fortunately, in most situations, it’s

not needed to write such boilerplate code: one of the methods from Uninterruptibles utility class from Guava can be used.

# IF.3. If an InterruptedException or a TimeoutException is caught on a

Future.get() call and the task behind the future doesn’t have side effects, i. e. get() is

called only to obtain and use the result in the context of the current thread rather than achieve

some side effect, is the future canceled?

See [JCIP 7.1] for more information about thread interruption and task cancellation.

# Tm.1. Are values returned from System.nanoTime() compared in an

overflow-aware manner, as described in the documentation for

this method?

# Tm.2. Isn't System.currentTimeMillis() used for time comparisons,

timed blocking, measuring intervals, timeouts, etc.? System.currentTimeMillis() is a subject to

the "time going backward" phenomenon. This might happen due to a time correction on a server, for

example.

System.nanoTime() should be used instead of currentTimeMillis() for the purposes of time

comparision, interval measurements, etc. Values returned from nanoTime() never decrease (but may

overflow — see the previous item). Warning: nanoTime() didn’t always uphold to this guarantee in

OpenJDK until 8u192 (see JDK-8184271). Make sure

to use the freshest distribution.

In distributed systems, the leap second adjustment causes similar issues.

# Tm.3. Do variables that store time limits and periods have suffixes identifying

their units, for example, "timeoutMillis" (also -Seconds, -Micros, -Nanos) rather than just

"timeout"? In method and constructor parameters, an alternative is providing a TimeUnit

parameter next to a "timeout" parameter. This is the preferred option for public APIs.

# Tm.4. Do methods that have "timeout" and "delay" parameters

treat negative arguments as zeros? This is to obey the principle of least astonishment because all

timed blocking methods in classes from java.util.concurrent.* follow this convention.

# Tm.5. Tasks that should happen at a certain system time, UTC

time, or wall-clock time far in the future, or run periodically with a cadence expressed in terms of

system/UTC/wall-clock time (rather than internal machine's CPU time) are not scheduled with

ScheduledThreadPoolExecutor? ScheduledThreadPoolExecutor (this class is also behind all

factory methods in Executors which return a ScheduledExecutorService) uses System.nanoTime()

for timing intervals. nanoTime() can drift against the system time and the UTC time.

CronScheduler is a scheduling class designed

to be proof against unbounded clock drift relative to UTC or system time for both one-shot or

periodic tasks. See more detailed recommendations on choosing between

ScheduledThreadPoolExecutor and CronScheduler.

On Android, use Android-specific APIs.

# Tm.6. On consumer devices (PCs, laptops, tables, phones),

ScheduledThreadPoolExecutor (or Timer) is not used for human interaction tasks or

interactions between the device and a remote service? Examples of human interaction tasks are

alarms, notifications, timers, or task management. Examples of interactions between user's device

and remote services are checking for new e-mails or messages, widget updates, or software updates.

The reason for this is that neither ScheduledThreadPoolExecutor nor Timer account for machine

suspension

(such as sleep or hibernation mode). On Android, use Android-specific APIs instead.

Consider CronScheduler as a replacement for

ScheduledThreadPoolExecutor in these cases for end-user JVM apps.

ThreadLocal

# TL.1. Can ThreadLocal field be static final? There are three cases

when a ThreadLocal cannot be static:

ThreadLocal-containing

instances).ThreadLocal may call another method (or the same method, recursively) that also

uses this ThreadLocal, but on a different containing object.enum) modelling a specific type of ThreadLocal usage, and there are only

limited number of instances of this class in the JVM: i. e. all are constants stored in

static final fields, or enum constants.If a usage of ThreadLocal doesn't fall into either of these categories, it can be static final.

There is an inspection "ThreadLocal field not declared static final" in IntelliJ IDEA which corresponds to this item.

Static ThreadLocal fields could also be enforced using Checkstyle, using the following combination

of checks:

<!-- Enforce 'private static final' order of modifiers -->

<module name="ModifierOrder" />

<!-- Ensure all ThreadLocal fields are private -->

<!-- Requires https://github.com/sevntu-checkstyle/sevntu.checkstyle -->

<module name="AvoidModifiersForTypesCheck">

<property name="forbiddenClassesRegexpProtected" value="ThreadLocal"/>

<property name="forbiddenClassesRegexpPublic" value="ThreadLocal"/>

<property name="forbiddenClassesRegexpPackagePrivate" value="ThreadLocal"/>

</module>

<!-- Prohibit any ThreadLocal field which is not private static final -->

<module name="Regexp">

<property name="id" value="nonStaticThreadLocal"/>

<property name="format"

value="^\s*private\s+(ThreadLocal|static\s+ThreadLocal|final\s+ThreadLocal)"/>

<property name="illegalPattern" value="true"/>

<property name="message" value="Non-static final ThreadLocal"/>

</module>

# TL.2. Doesn't a ThreadLocal mask issues with the code, such as poor

control flow or data flow design? Is it possible to redesign the system without using

ThreadLocal, would that be simpler? This is especially true for instance-level (non-static)

ThreadLocal fields; see also TL.1 and TL.4 about them.

See Dc.2 about the importance of articulating the control flow and the data flow of a subsystem which may help to uncover other issues with the design.

# TL.3. Isn't a ThreadLocal used only to reuse some small heap

objects, cheap to allocate and initialize, that would otherwise need to be allocated relatively

infrequently? In this case, the cost of accessing a ThreadLocal would likely outweigh the

benefit from reducing allocations. The evidence should be supplied that introducing a ThreadLocal

shortens the GC pauses and/or increases the overall throughput of the system.

# TL.4. If the threads which execute code with usage of a non-static

ThreadLocal are long-living and there is a fixed number of them (e. g. workers of a fixed-sized

ThreadPoolExecutor) and there is a greater number of shorter-living ThreadLocal-containing

objects, was it considered to replace the instance-level ThreadLocal<Val> with a