Security News

PyPI’s New Archival Feature Closes a Major Security Gap

PyPI now allows maintainers to archive projects, improving security and helping users make informed decisions about their dependencies.

You know what I really like in React - it teaches you how to build well encapsulated components that are also highly composable. The thing is that React and its JSX is for our UI. It is a view layer that renders stuff on the screen. I wanted something similar but for my business logic. Something that allows me to use the same patterns but helps me deal with the asynchronous nature of the front-end development. So, I did it. Meet ActML - like React but for your business logic.

Wouldn't be cool if we can define a function and execute it the same way as we render React component. Like for example:

const Greeting = function () {

return 'Hey!';

}

run(<Greeting />).then(

message => console.log(message)

);

What if we have more functions, they depend on each other and one of them is asynchronous:

const GetUserFirstName = async function() {

const result = await fetch('https://reqres.in/api/users/2');

return (await result.json()).data.first_name;

};

const Greeting = function({ name }) {

return `Hello ${name}`;

};

const Print = function({ message }) {

console.log(message);

};

run(

<A>

<GetUserFirstName exports="name" />

<Greeting $name exports="message" />

<Print $message />

</A>

);

Let's see step by step what ActML does:

<A> element is just a wrapper that comes with ActML module.<GetUserFirstName> is making a request to https://reqres.in/api/users/2 and gets the first name of the user. It is an asynchronous function so ActML waits till its promise is resolved. When using it we say that it exports a variable called name.<Greeting> needs that name variable and uses the special dollar sign notation which to ActML processor means "Inject a variable with name name as a prop".<Greeting> also formats a message and returns it as a result.<Print> just gets the message and prints it out in the console.Here is a working Codesandbox of the code.

So, that is the concept of ActML. It allows us to define in a declarative fashion our business logic. Same as our UI. In fact all the code that we pass to the run function is nothing but definitions of what should happen. It is not saying how. This is extremely powerful concept because it shifts the imperative code to another level and gives us more options for composition.

ActML uses React's JSX transpiler to convert markup to function calls. By default the transpiler translates every tag to a React.createElement call so to make your code works with ActML you have to add

/** @jsx A */

import { A } from 'actml';

The first line is to say that we don't want React.createElement() but A(). The second line is there because otherwise you'll get ReferenceError: A is not defined error. And of course because the A function is defining the core unit of ActML - an ActML element.

From a tools perspective you need some sort of Babel integration. There's a React+Redux+ActML example app here that you can check.

In the context of ActML the element is a JavaScript function. The code below defines two different ActML elements:

/** @jsx A */

import { A, run } from 'actml';

const Foo = function () { console.log('Foo'); }

const Bar = function () { console.log('Bar'); }

run(

<A>

<Foo />

<Bar />

</A>

);

// > Foo

// > Bar

To be more specific the element may be three things:

the ActML processor executes the functions from the outer to inner ones and from top to bottom. All the three types of elements may return another element. In the case of generator we may yield also another element. For example:

function Print({ message }) {

console.log(message);

}

async function GetSeason({ endpoint }) {

const result = await fetch(endpoint);

const { season } = await result.json();

return season;

}

function * Logic() {

const season = yield (

<GetSeason endpoint="https://www.mocky.io/v2/5ba2a2b52f00006a008d2e0d" />

);

if (season === 'not summer') {

yield <Print message="No beach!" />;

} else {

yield <Print message="Oh yeah!" />;

}

}

run(<Logic />); // prints out: No beach!

Codesandbox with the example.

The scope API is a mechanism for transferring data between ActML elements.

In React there are couple of approaches to pass data between components. One of them is the FaCC (function as child component) pattern. Let's focus on it and see how it looks like in ActML:

const Foo = function ({ name, children }) {

children({ message: `Hello ${ name }` });

}

run(

<Foo name='John'>

{

({ message }) => console.log(message)

}

</Foo>

);

// outputs "Hello John"

That's nice but we can't use FaCC everywhere. And we have to do that a lot because that's not React but our business logic. We will probably have dozen of functions that need to communicate between each other. So there is a Scope API that can keep data and share it with other elements. Let's take the following example:

const Foo = () => 'Jon Snow';

const App = () => {};

const Zoo = ({ name }) => console.log('Zar: ' + name);

const Bar = ({ name }) => console.log('Bar: ' + name);

run(

<App>

<Foo exports='name'>

<Zoo $name />

</Foo>

<Bar $name />

</App>

);

Every ActML element has a scope object. It is really just a plain JavaScript object {} and every time when we use exports we are saving something there. For example the scope object of the Foo element is equal to { name: 'Jon Snow' }. Together with creating the name variable in the scope of Foo we are also sending an event to the parent App element. Then the App element should decide if it is interested in that variable or not. If yes then it keeps it in its scope. In the example above that is not happening so the name variable is only set in the scope of <Foo>. That is why in this latest example we will get Zar: Jon Snow followed by the error Undefined variable "name" requested by <Bar>..

To solve the problem we have to instruct <App> element to catch the name variable and also keeps it in its scope. This happens by the special prop called scope:

const Foo = () => 'Jon Snow';

const App = () => {};

const Zoo = ({ name }) => console.log('Zar: ' + name);

const Bar = ({ name }) => console.log('Bar: ' + name);

run(

<App scope='name'>

<Foo exports='name'>

<Zoo $name />

</Foo>

<Bar $name />

</App>

);

Now the result of <Foo> is available for <Bar> element too. The value of name is consistent across the different scopes. Changing it in one place means that it is updated in the other ones too.

Another important note here is that once a variable gets caught it doesn't bubble up. If there are other elements as parents they will not receive it.

There is a special * (star) value that we can pass to the scope prop which means "Catch all the variables". The example above will look like this:

<App scope='*'>

<Foo exports='name'>

<Zoo $name />

</Foo>

<Bar $name />

</App>

For convenience the element <A> has its scope property set to * by default. So <App scope='*'> could be just replaced by <A>. Or in other words if we want to catch all the variables we may use <A> directly.

The exports prop may also accept a function. The function receives the result of the element and must return an object (key-value pairs). This approach is useful when we want to apply some transformation of the element's result without modifying the actual element. For example:

const Foo = () => 'Jon Snow';

const transform = name => ({

originalName: name,

lowercaseName: name.toLowerCase(),

uppercaseName: name.toUpperCase()

});

run(

<A>

<Foo exports={ transform }>

<Zoo $lowercaseName />

</Foo>

<Bar $uppercaseName />

</A>

);

<Zoo> and <Bar> now accept lowercaseName and uppercaseName as props. This however may be too long for typing. We can rename those like so:

run(

<A>

<Foo exports={ transform }>

<Zoo $lowercaseName="name" />

</Foo>

<Bar $uppercaseName="name" />

</A>

);

We can also pass a function and apply some transformation of the data before importing.

<Bar $uppercaseName={ name => ({ len: name.length }) } />

<Bar> element will receive a prop called len which contains the number of letters in the uppercaseName variable.

Now when you know about the scope API we could make a parallel with the context API. The scope API is more like a local placeholder of data. While the context API is globally available and it is more about injecting elements.

The run function accepts a second argument which is the custom context. We can pass an object in the format of key-value pairs. For example:

const Zoo = ({ message }) => console.log('The message is: ' + message);

const context = {

getMessage({ name }) {

return `Hello ${name}!`;

}

};

run(

<getMessage name="Jon Snow" exports="message">

<Zoo $message />

</getMessage>,

context

);

// Prints out: The message is: Hello Jon Snow!

Notice how getMessage is defined in the context. We have to stress out that this is only possible because of the JSX transpiler. Everything that goes into the context must start with a lower case letter. That is because:

<getMessage />

gets transpiled to

A("getMessage", null);

while

<GetMessage />

to

A(GetMessage, null);

In the second case there must be a function called GetMessage while in the first case there's just a string getMessage passed to ActML processor. This may looks weird but is really powerful API for delivering dependencies deep down your ActML tree. Imagine how you define your context once and then write your logic distributed between different files.

The input to your ActML element is the attributes that we pass to the tag or if we have to make a parallel with React - the props. For example:

const Foo = function (props) {

console.log(`Hello ${ props.name }`);

}

run(<Foo name='John' />); // outputs "Hello John"

There are couple of prop names that can not be used because they have a special meaning/function.

children propActML does not process children which are not ActML elements. This means that we may pass just a regular JavaScript function and our ActML will still work. The thing is that this function will not be fired by the ActML processor. We must do that manually by calling the children prop:

const Foo = function({ name, children }) {

children({ text: `Hello ${name}` });

};

run(

<Foo name="John">

{

({ text }) => console.log(text)

}

</Foo>

);

// outputs "Hello John"

This is actually the so called FACC (function as children pattern) which we know from writing React apps.

The children used as a function accepts only an object (key-value pairs). And that's done for a reason. Let's explore the next example:

const Foo = function({ name, children }) {

children({ text: `Hello ${name}` });

};

const Print = function({ text }) {

console.log(text);

};

run(

<Foo name="John">

(<Print $text />)

</Foo>

);

// outputs "Hello John"

The result is the same but this time we are using an ActML as a child and not an JSX expression. The argument must be an object because it gets set as a scope of <Foo> (read more about the scope API here). That's how we may access the Hello John via the $text prop.

You probably noticed that <Print> is wrapped into parentheses. This is to instruct the processor that the element (or elements) must not be processed. We will take care by calling children. If we forget to add parentheses we will get the following error:

You are trying to use "children" prop as a function in <Foo> but it is not.

Did you forget to wrap its children into parentheses.

Like for example <Foo>(<Child />)</Foo>?

exports propThe exports prop defines a new entry in the scope of the element or in some of its parents (read about that in the scope API section).

const Foo = function() {

return 42;

}

<Foo exports='answer' />

The scope of the <Foo> is equal to { answer: 42 }.

We may also pass a function and apply some transformation before storing the data in the scope. The function must return an object (key-value pairs).

const Foo = () => 42;

const Print = ({ bar }) => console.log(bar);

run(

<Foo exports={value => ({ bar: value * 2 })}>

<Print $bar />

</Foo>

);

// outputs: 84

We already saw that on a couple of places. It is basically to say that we want a value which is available in the scope of the parent (or some of its parents) scope.

const Foo = () => 42;

const Print = ({ answer }) => console.log(answer);

run(

<Foo exports="answer">

<Print $answer />

</Foo>

);

// outputs: 42

If we don't like the naming we may change it by providing a string as a value. For example:

const Foo = () => 42;

const Print = ({ banana }) => console.log(banana);

run(

<Foo exports="answer">

<Print $answer="banana" />

</Foo>

);

// outputs: 42

We may also provide a function and produce whatever new prop (or props) we want:

const Foo = () => 42;

const Print = ({ a, b }) => console.log(`${ a }, ${ b }`);

run(

<Foo exports="answer">

<Print $answer={ value => ({ a: value, b: value * 2 })} />

</Foo>

);

// outputs: 42, 84

scope propThe scope prop is used to catch variables exported by other nested elements. This is to make some data available to a broader portion of the ActML tree.

const Foo = () => 'Jon Snow';

const App = () => {};

const Zoo = ({ name }) => console.log('Zar: ' + name);

const Bar = ({ name }) => console.log('Bar: ' + name);

run(

<App scope='name'>

<Foo exports='name'>

<Zoo $name />

</Foo>

<Bar $name />

</App>

);

Normally $name is not available for <Bar> because it is exported by a sibling <Foo>. However <App> is catching it and it makes it available for <Bar>.

The scope prop accepts a single name or comma separated list. It also accepts * as a value which means catch everything. The build-in <A> element has this by default.

There are some predefined elements that come with ActML core package.

<A>The <A> element has the ability to scope everything. So if you need that functionality and you a wrapper this is a good element to use.

Because run returns a promise we can just catch the error at a global level:

const Problem = function() {

return iDontExist; // throws an error "iDontExist is not defined"

};

run(

<A>

<Problem />

</A>

).catch(error => {

console.log('Ops, an error: ', error.message);

// Ops, an error: iDontExist is not defined

});

That's all fine but it is not really practical. What we may want is to handle the error inside our ActML. In such cases we have the special onError prop. It accepts another ActML element which receives the error as a prop.

const Problem = function() {

return iDontExist;

};

const HandleError = ({ error }) => console.log('Ops!');

run(

<A>

<Problem onError={ <HandleError /> } />

</A>

);

// outputs: Ops!

If we are handling the error the ActML processor assumes that we know what we are doing and does not stop the execution. For example:

const Problem = function() {

return iDontExist;

};

const Foo = () => console.log('I am still here');

const HandleError = ({ error }) => console.log('Ops!');

run(

<A>

<Problem onError={<HandleError />} />

<Foo />

</A>

);

// outputs "Ops!" followed by "I am still here"

And of course we may still stop the processing by throwing error from inside our handler.

FAQs

Like jsx but for your business logic

The npm package actml receives a total of 16 weekly downloads. As such, actml popularity was classified as not popular.

We found that actml demonstrated a not healthy version release cadence and project activity because the last version was released a year ago. It has 1 open source maintainer collaborating on the project.

Did you know?

Socket for GitHub automatically highlights issues in each pull request and monitors the health of all your open source dependencies. Discover the contents of your packages and block harmful activity before you install or update your dependencies.

Security News

PyPI now allows maintainers to archive projects, improving security and helping users make informed decisions about their dependencies.

Research

Security News

Malicious npm package postcss-optimizer delivers BeaverTail malware, targeting developer systems; similarities to past campaigns suggest a North Korean connection.

Security News

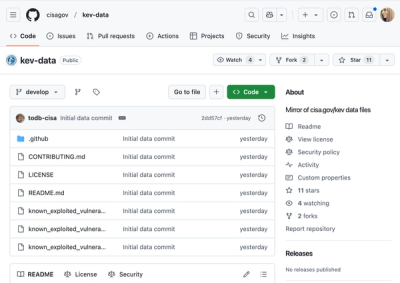

CISA's KEV data is now on GitHub, offering easier access, API integration, commit history tracking, and automated updates for security teams and researchers.