Research

Security News

Malicious npm Packages Inject SSH Backdoors via Typosquatted Libraries

Socket’s threat research team has detected six malicious npm packages typosquatting popular libraries to insert SSH backdoors.

Behaviour Assertion Sheets: CSS-like declarative syntax for client-side integration testing and quality assurance.

(For a friendlier overview, see http://bas.cgiffard.com/)

Behaviour Assertion Sheets (Bas, pronounced 'base') are a way to describe how a web page fits together, make assertions about its structure and content, and be notified when these expectations are not met. It's a bit like selenium, if you've ever used that. An easier DSL for client-side integration testing.

You could:

Anybody who has ever used CSS can use Bas - the [syntax is easy and familiar.] (#sheet-syntax)

This first implementation of Bas is built with node.js, so you'll need it and npm first. Then just use npm to install Bas:

npm install -g bas

Installing globally (-g) makes a CLI tool available

for working with Bas sheets. If you don't install globally you can still use Bas

via the node.js API.

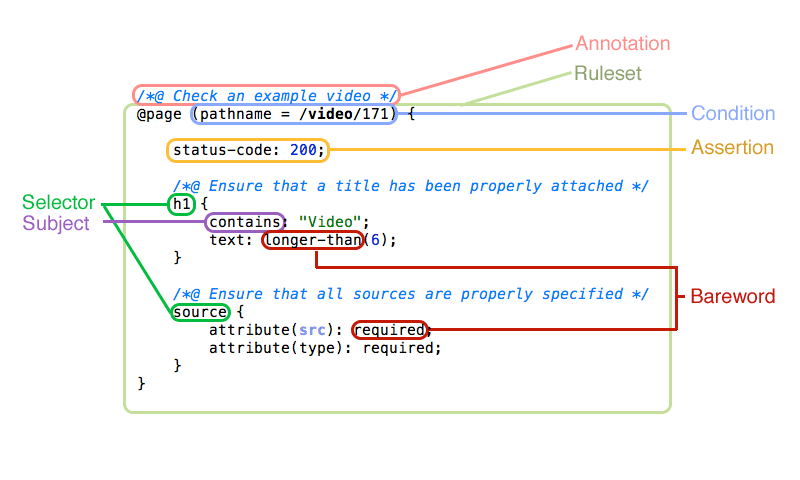

As mentioned earlier, the Bas syntax looks very similar to (and nearly even parses as) CSS. Here are the major components:

(You can work this out yourself and just want to skip to the goods? Jump to syntax example.)

Rulesets are the highest-level construct in Bas. Everything falls inside a ruleset.

There are two kinds of rulesets - page specific rulesets denoted by the tag @page,

and rulesets that execute against every page unconditionally, denoted by the

tag @all.

Syntactically these are based on the 'at-rules' of CSS (such as @font-face,

@media, etc.)

Rulesets cannot be nested.

An example rulset:

@all {

...

}

Annotations are an extension of CSS comments, that are prepended with an @ symbol.

Bas knows to associate these with rulesets and selectors that follow, and displays

them in assertion failure traces so you know where they came from!

You may add as many annotations as you like to a single element. Every annotation

that precedes a block, regardless of whether assertions or regular comments (just

normal CSS comments without an @) are interspersed within them, is associated

with that block.

An example annotation:

/*@ Here's my annotation! */

A condition is appended to a page-specific ruleset (@page) and determines based

on the response information, URL of the page, and other environment variables,

whether the current page should be evaluated against this ruleset.

Conditions are additive and exclusive - each has to be true for the page to be

considered for testing against a given ruleset. You may add as many conditions

as you like to a @page ruleset.

Conditions are composed of a parentheses-wrapped set of three elements, each space

separated. On the left-hand side, a test - a reference to a function which

returns an environment variable or extracts an aspect of the current page or

server response.

The middle is an operator, which defines how the comparison takes place. An example

of an operator might be = or >= or !=~. A full list of operators can be

found in the syntax glossary.

The rightmost component is the assertion value - a string, number, or regular expression which is compared to the test according to the rules of the operator.

An example condition:

@page (status-code = 301) { ... }

Multiple conditions may be combined like so:

@page (status-code = 301) (content-type != text/html) { ... }

Remember that adding more conditions will make the match more exclusive, as every single one must succeed for the ruleset to be evaluated.

A selector groups a block of assertions together, and executes them against every node in a page that matches the selector string.

The selector string is formatted exactly like a regular CSS selector - tags, IDs, classes, pseudoclasses, and attribute syntax are all the same.

The assertions wrapped within a selector block are only executed should the

selector match at least one node - with one exception: the special required

assertion subject which executes regardless of whether a

selector matches.

There's a caveat to this too, though: should a selector containing the required

assertion subject be nested inside another selector block which does not match

any nodes, it will not be executed. This allows syntax like the following:

h2 {

h1 { required: true; }

}

In this case, the heading 1 is required if one or more second-level headings are present.

Selector blocks can be nested. If a selector block is nested within another, it will only be executed should the parent selector match.

When selector blocks are nested, special scoping variables may be used.

The scoping variable $this maps to the parent selector block's selector string.

Therefore, consider the following example:

#content {

$this b {

/* Hey! */

}

}

The inner selector $this b will map to #content b.

The $node scope is similar to $this — however it is even more restrictive,

only searching within the exact node (or nodes) which was/were selected.

#content header {

$node h3 {

}

}

In the above example, $node h3 is equivalent to a scoped search for h3 within

each individual element matching #content header.

Selectors may contain values interpolated from test results executed in their parent context.

For example, lets say you want to make sure that any element with an

aria-describedby attribute has a matching element ID somewhere on the page.

/* ARIA attributes */

$this [aria-describedby] {

/*@ WCAG (1.3.1 A, 4.1.1 A, 4.1.2 A) There must be a tag with a matching ID

for the aria-describedby attribute */

[id=$(attribute(aria-describedby))$] {

count: 1;

required: true;

}

}

The $(...)$ construct instructs Bas to execute the string

attribute(aria-describedby) as a test, and return the result, interpolating it

into the selector.

Therefore, the final interpolated selector might look like:

[id=image-header]

An assertion is very similar to a declaration in CSS. Fundamentally, it is a

semicolon delimited key-value pair, that unlike CSS, defines an expectation

rather than assigning a value.

The left-hand side of the assertion is known as the subject of the assertion, and refers to a test - a function that returns a value based on the content of the current page/request.

This value is then compared against the right-hand side of the assertion - which

can contain any number of match requirements, separated by commas and/or spaces.

These requirements are evaluated separately, and should any single one of them

fail (return a falsy value) the assertion will be considered failed.

Match requirements for an assertion can be strings, numbers, regular expressions, negated regular expressions (prepended with !) or barewords.

An example of an assertion in use:

attribute(style): contains("font-family");

The left-hand side of every assertion is known as an assertion subject, and

refers to a test function that returns a value from the current page or response

information. A list of these functions can be found in the [syntax glossary.]

(#tests)

An example of an assertion subject in use might be:

title: /github/i;

In this case, the assertion subject is title. It refers to a test function called

title which extracts the current document title. This is returned for the regex

comparison on the right hand side of the assertion.

Some tests take arguments. This is how an assertion with test arguments is represented:

attribute(role): "main";

The value of an assertion test function can be subsequently transformed by special functions known as transform functions.

These can be chained against the value of an assertion test using the delimiter ..

Purely for illustrative purposes, here's an example of using transform functions (fictitious... for now) to rot-13 text from a node before validating the assertion:

h1 {

text.rot13: /* some match here... */

}

Multiple transforms can be applied:

h1 {

text.rot13.rot13: /* text is back to normal! */

}

And arguments can be provided to transform functions, just like to the subject test itself.

h1 {

text.rot(13): /* some match here... */

text.rot(13).rot(13): /* some match here... */

}

A more realistic use-case can be found in the text-statistics functions. If you want to check the flesch-kincaid reading ease of a given node, you could use:

h1 {

text.flesch-kincaid-reading-ease: gte(80);

}

You could check the reading-ease of the alt-text on an image, too:

img {

attribute(alt).flesch-kincaid-reading-ease: gte(80);

}

The right-hand side of the assertion, as well as regular expression, numeric, and string matches, can contain special keywords known as barewords (for their lack of enclosing quotation marks.)

These keywords refer to a special function that by design has no access to the document - just the value returned by the assertion subject, and any optional arguments it is given.

If the result of this function is falsy, then the assertion is considered failed.

A full list of barewords can be found in the syntax glossary.

An example of barewords in use:

attribute(user-id): exists, longer-than(1), gte(1);

@page (title =~ /github/i) (domain = github.com) {

status-code: 200;

img[src*="akamai"] {

required: true;

attribute(alt): true;

count: 3;

}

/*@ Require a heading 1 to be present if there's a heading 2 */

h2 {

h1 {

required: true;

}

}

}

@all {

status-code: lt(500);

}

This example provides a fairly broad look at what Bas can do and how it works.

Let's break this example down bit by bit.

Given a page from the domain github.com, with a document title that matches the

regular expression /github/i:

200 OK.akamai somewhere in the in the src

attribute, and:

alt attributeThen, on every page tested, Bas will check to see whether the status code of the response was less than 500.

Operators are used in ruleset conditions, like (title !=~ /github/i).

A full list follows:

= true if a == b!= true if a !== b=~ true if the regular expression a matches b!=~ true if the regular expression a does not match b> true if a > b where both a and b are considered floats< true if a < b where both a and b are considered floats>= true if a >= b where both a and b are considered floats<= true if a <= b where both a and b are considered floatsTests without arguments may be used in ruleset conditions, like

(title !=~ /github/i), or as assertion subjects with or without arguments, like

attribute(role): "navigation".

Tests can also be added programatically. [See the API documentation for details.] (#bas-nodejs-api)

query parameter attribute is present, the individual value for the specified query

parameter will be returned, or null if the parameter does not exist.Content-Length header with which the current document was served.Content-Type header with which the current document was served.required..length property of the input.Barewords are used in assertions to evaluate the result of a test. Barewords can have arguments.

If you installed Bas globally, you'll have access to a bas CLI

client which (hopefully) is available in your $PATH.

The bas CLI client can request a series of URLs, or initiate a crawl using the

provided list of URLs as a seed.

If you want to use Bas in another, non-JS project or in some kind of automated

capacity from the shell, you can supply a -j option to get test results as raw

JSON.

Here's a very simple example of how you might use the CLI tool:

bas -vc -s mysheet.bas http://www.mywebsite.com/

In this example, the file mysheet.bas would be loaded and, with verbose reporting,

a crawl of mywebsite.com initiated (the -c option starts a crawl.) The test

suite would be run against every page returned, for as many pages as are present

and accessible from the given URL. Obviously it may make sense to limit the number

of pages downloaded: you can do this with the -l option:

bas -vc -l 10 -s mysheet.bas http://mywebsite.com/

You may specify a single numeric range using a simple interpolation:

bas -vc -l 10 -s mysheet.bas http://mywebsite.com/node/%{20-500}

If the -s option isn't specified, bas will look for the assertion sheet on

STDIN. Therefore, you can cat a file and pipe it to bas as well:

cat mysheet.bas | bas -v http://mydomain.com/testfile.html

Or, if you haven't piped anything, bas will prompt you to enter the sheet

information manually:

➭ bas -v http://www.regex.info

Waiting for BAS input from STDIN.

@all {

h1 { required; }

}

^D

Thanks, got it.

<snip>

Here's the full list of options supported by bas at this time: (you can also

get a list of options by typing bas -h at the prompt.)

-h, --help Output usage information-V, --version Output the version number-c, --crawl Crawl from the specified URLs-s, --sheet [filename] Test using the specified BAS-l, --limit [number] Limit number of resources to request when crawling-d, --die Die on first error-q, --quiet Suppress output (prints final report/json only)-v, --verbose Verbose output-j, --json Output list of errors/test results as JSON--csv Output list of errors/test results as CSV--noquery Don't download resources with query strings-u, --username <username> Username for HTTP Basic Auth (crawl)-p, --password <password> Password for HTTP Basic Auth (crawl)The exit value from the CLI is equivalent to the number of errors that occurred when the test suite was run. If no errors occurred, of course, the exit value is zero.

The Bas API is extremely straightforward. To get started, simply require it:

var BAS = require("bas");

Create yourself a new BAS test suite like so:

var testSuite = new BAS();

Load in a Bas sheet (you can also supply a buffer if you'd prefer.)

testSuite.loadSheet("./mysheet.bas");

Then fetch a resource (in this case, we're using request) and run the test suite against it. You'll need to pass in a URL and response object as well as the page data.

request("http://example.com",function(err,res,body) {

if (err) throw err;

testSuite.run(url,res,data);

});

The test suite runs asynchronously, and emits events so you can know when errors have occurred, assertions have been tested, or that the suite has completed.

We can listen to one of these events to be alerted to when the test suite finishes, and receive a list of errors (if there were any!)

testSuite.on("end",function() {

if (testSuite.errors.length) {

console.log("Looks like there were some errors!");

testSuite.errors.forEach(function(err) {

console.error(err.message);

});

}

});

new BAS( [options] )

Returns a new Bas test suite instance. The optional options parameter is an

object, with the following possible keys:

continueOnParseFail (Defaults to false)

Should Cheerio fail to parse the HTML document, should Bas continue with the

test suite, loading in a blank document? Or bail out?BAS is an instance of node EventEmitter and implements the on and emit methods,

not described here.

BAS.tests propertyGetter: Returns an object map of functions corresponding to tests

BAS.errors propertyGetter: returns an array of assertion errors (Error instances) if any were thrown during the previous test run.

Each error has the following (some additional) properties:

message (string - the error message.)selector (string - if available, the selector that triggered the current

assertion.)nodePath (string - a generated, unambiguous CSS selector path to the current node.)url (string - the url of the page that triggered this assertion.)The list of errors may also be cleared with BAS.errors.clear().

BAS.rules propertyGetter: An array of ruleset objects. (Better documentation for these coming soon!)

BAS.stats propertyGetter: Returns an object containing statistics about past test runs.

This should be considered unstable and undocumented. It is about to change.

BAS.loadSheet (buffer sheetData | string filePath)If given a buffer, this function will not touch the filesystem - it simply parses the data it receives immediately.

If given a filepath, asynchronously loads the entire file off disk, and parses it - adding the processed rules to the test suite object.

These rules can be accessed via BAS.rules.

This function returns an object with promise handlers: yep for success, and nope

for failure. See the yoyaku documentation for

more information.

BAS.parseSheet (buffer sheetData | string sheetData)Takes a string or a buffer containing Bas rules, and parses it, adding the processed rules to the test suite object.

These rules can be accessed via BAS.rules.

This function returns an object with promise handlers: yep for success, and nope

for failure. See the yoyaku documentation for

more information.

BAS.registerTest(string testName, function test)Registers a test in the BAS.test object map - and makes it available to Bas

sheets to use in conditions and assertion subjects.

BAS.run (string URL, object HTTPResponse, string Data)Initiates the running of the test suite.

It is important to give this function the correct URL and response object, or the tests may not operate correctly.

BAS will emit events during the execution of the tests.

This function returns an object with promise handlers: yep for success, and nope

for failure. See the yoyaku documentation for

more information.

loadsheet

Emitted when a new Bas sheet is successfully loaded.testregistered (name, func)

Emitted when a new test is registered with Bas.start (url)

Emitted when the test suite commences.parseerror (error)

Emitted when Cheerio encounters a parse error with the resource.assertion (assertion, [node])

Emitted when Bas begins testing an assertion. The node parameter is only

supplied when testing an assertion in a selector group.assertionsuccess (assertion, [node])

Emitted when Bas completes testing an assertion, and the result is truthy.

The node parameter is only supplied when testing an assertion in a selector

group.assertionfailed (assertionErr, assertion)

Emitted when Bas completes testing an assertion, and the result is falsy, and

the test is considered failed. The error triggered by the assertion is supplied

as the first parameter.selector (selector, node)

Emitted when Bas commences testing the assertions in a selector.startgroup (rule)

Emitted when Bas commences testing the assertions in a ruleset.end (url,errors)

Emitted when Bas completes the test suite. An array of errors is provided,

and the URL of the page the tests were executed against.bas CLI toolBas does not have an enormous test suite at this stage, but I'm working on filling it out as comprehensively as possible.

To run the test suite, use:

npm test

Test coverage is generated with istanbul.

To generate current statistics, run npm run-script coverage from the Bas directory.

| Statements | Branches | Functions | Lines |

|---|---|---|---|

| 82.86% (551/665) | 77.51% (286/369) | 79.86% (115/144) | 82.78% (519/627) |

Copyright (c) 2013, Christopher Giffard.

All rights reserved.

Redistribution and use in source and binary forms, with or without modification, are permitted provided that the following conditions are met:

THIS SOFTWARE IS PROVIDED BY THE COPYRIGHT HOLDERS AND CONTRIBUTORS "AS IS" AND ANY EXPRESS OR IMPLIED WARRANTIES, INCLUDING, BUT NOT LIMITED TO, THE IMPLIED WARRANTIES OF MERCHANTABILITY AND FITNESS FOR A PARTICULAR PURPOSE ARE DISCLAIMED. IN NO EVENT SHALL THE COPYRIGHT HOLDER OR CONTRIBUTORS BE LIABLE FOR ANY DIRECT, INDIRECT, INCIDENTAL, SPECIAL, EXEMPLARY, OR CONSEQUENTIAL DAMAGES (INCLUDING, BUT NOT LIMITED TO, PROCUREMENT OF SUBSTITUTE GOODS OR SERVICES; LOSS OF USE, DATA, OR PROFITS; OR BUSINESS INTERRUPTION) HOWEVER CAUSED AND ON ANY THEORY OF LIABILITY, WHETHER IN CONTRACT, STRICT LIABILITY, OR TORT (INCLUDING NEGLIGENCE OR OTHERWISE) ARISING IN ANY WAY OUT OF THE USE OF THIS SOFTWARE, EVEN IF ADVISED OF THE POSSIBILITY OF SUCH DAMAGE.

FAQs

Behaviour Assertion Sheets: CSS-like declarative syntax for client-side integration testing and quality assurance.

We found that bas demonstrated a not healthy version release cadence and project activity because the last version was released a year ago. It has 2 open source maintainers collaborating on the project.

Did you know?

Socket for GitHub automatically highlights issues in each pull request and monitors the health of all your open source dependencies. Discover the contents of your packages and block harmful activity before you install or update your dependencies.

Research

Security News

Socket’s threat research team has detected six malicious npm packages typosquatting popular libraries to insert SSH backdoors.

Security News

MITRE's 2024 CWE Top 25 highlights critical software vulnerabilities like XSS, SQL Injection, and CSRF, reflecting shifts due to a refined ranking methodology.

Security News

In this segment of the Risky Business podcast, Feross Aboukhadijeh and Patrick Gray discuss the challenges of tracking malware discovered in open source softare.