Security News

Research

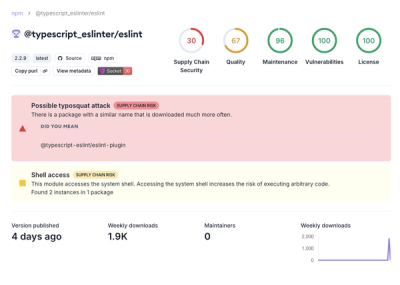

Data Theft Repackaged: A Case Study in Malicious Wrapper Packages on npm

The Socket Research Team breaks down a malicious wrapper package that uses obfuscation to harvest credentials and exfiltrate sensitive data.

asyncioThe main and single purpose of this library is to allow for the static description of scenarii involving asyncio-compliant jobs, that have dependencies in the sense that a given job cannot start until its requirements have not completed.

So in a nutshell you would:

Job objects,requires relationship; that is to say, for each of them, which other jobs need to have completed before this one can be triggered,Scheduler object, that will orchestrate the whole scenario.Further features allow to

timeout for the whole scheduler;Scheduler instance being also a job, a scheduler can be inserted in another scheduler just as if it were a re gular job; nested schedulers allow for reusability, since workflow pieces can be for example returned by regular python functions.A job object can be created:

Job instance from a regular asyncio coroutine;AbstractJob class, and defining its co_run() method; this is for example the case for the SshJob in the apssh library.As a convenience, the Sequence class is a helper class that can free you from manually managing the requires deps in long strings of jobs that must run sequentially.

This document, along with asynciojobs's API reference documentation, and changelog, is available at http://asynciojobs.readthedocs.io

Contact author: thierry dot parmentelat at inria dot fr

Licence: CC BY-NC-ND

asynciojobs requires asyncio and python-3.5 or more recent.

import sys

major, minor = sys.version_info[:2]

if (major, minor) < (3, 5):

print("asynciojobs won't work in this environment")

asynciojobs requires python-3.5, and can be installed from the pypi repository:

pip3 install asynciojobs

graphvizThis installation method will not try to install the graphviz python package, that can be cumbersome to install, and that is not strictly necessary at run-time for orchestrating a scheduler.

We recommend to install it for developping scenarios though since, as we will see shortly, asynciojobs provides a graphical representation of schedulers, that is very convenient for debugging.

import asyncio

In all our examples, we will use the Watch class, it is a helper class that works like a stopwatch; instead of printing the current time, we prefer to display running time from the beginning, which corresponds to the time where the watch instance is created or reset:

import time

from asynciojobs import Watch

watch = Watch()

time.sleep(0.5)

watch.print_elapsed('some')

000.000

000.505 some

We can now write a simple coroutine for illustrating schedulers through small examples:

import time

watch = Watch()

# just print a message when entering and exiting, and sleep in the middle

async def in_out(timeout):

global watch

watch.print_elapsed("-> in_out({})\n".format(timeout))

await asyncio.sleep(timeout)

watch.print_elapsed("<- in_out({})\n".format(timeout))

# return something easy to recognize: the number of milliseconds

return 1000 * timeout

000.000

Running a series of coroutines in parallel - a la gather - can be done like this:

from asynciojobs import Job, Scheduler

a1, a2, a3 = Job(in_out(0.1)), Job(in_out(0.2)), Job(in_out(0.25)),

What we're saying here is that we have three jobs, that have no relationships between them.

So when we run them, we would start all 3 coroutines at once, and return once they are all done:

# this is required in our case because our coroutines

# use watch to show time elapsed since reset()

watch.reset()

sa = Scheduler(a1, a2, a3)

sa

Scheduler with 0 done + 0 ongoing + 3 idle = 3 job(s)

sa.run()

000.016 -> in_out(0.1)

000.016 -> in_out(0.2)

000.016 -> in_out(0.25)

000.119 <- in_out(0.1)

000.219 <- in_out(0.2)

000.269 <- in_out(0.25)

True

Note: the run() method is a regular python function, which is easier to illustrate in this README, but in practical terms it is only a wrapper around the co_run() coroutine method.

The library offers great flexibility for creating schedulers and jobs. In particular in the example above, we have created the jobs first, and then added them to the scheduler; it is possible to do it the other way around, like this totally equivalent construction:

# if it is more to your taste, you can as well

# create the scheduler first

sa2 = Scheduler()

# and then add jobs in it as you create them

a1, a2 = Job(in_out(0.1), scheduler=sa2), Job(in_out(0.2), scheduler=sa2)

# or add them later on

a3 = Job(in_out(0.25))

sa2.add(a3)

Scheduler with 0 done + 0 ongoing + 3 idle = 3 job(s)

watch.reset()

sa2.run()

000.000 -> in_out(0.1)

000.000 -> in_out(0.2)

000.000 -> in_out(0.25)

000.105 <- in_out(0.1)

000.205 <- in_out(0.2)

000.254 <- in_out(0.25)

True

We can see right away how to retrieve the results of the various jobs

a1.result()

100.0

Now we can add requirements dependencies between jobs, as follows. Here we want to run:

We take this chance to show that jobs can be tagged with a label, which can be convenient for a more friendly display.

b1, b2, b3 = (Job(in_out(0.1), label="b1"),

Job(in_out(0.2), label="b2"),

Job(in_out(0.25)))

b2.requires(b1)

Now b2 needs b1 to be finished before it can start. And so only the 2 first coroutines get started at the beginning, and only once b1 has finished does b2 start.

watch.reset()

# with this setup we are certain that b3 ends in the middle of b2

sb = Scheduler(b1, b2, b3)

sb.run()

000.000 -> in_out(0.1)

000.000 -> in_out(0.25)

000.103 <- in_out(0.1)

000.104 -> in_out(0.2)

000.255 <- in_out(0.25)

000.309 <- in_out(0.2)

True

SequenceThe code above in example B is exactly identical to this:

from asynciojobs import Sequence

sb2 = Scheduler(

Sequence(Job(in_out(0.1), label="bp1"),

Job(in_out(0.2), label="bp2")),

Job(in_out(0.25)))

watch.reset()

sb2.run()

000.000 -> in_out(0.1)

000.000 -> in_out(0.25)

000.104 <- in_out(0.1)

000.104 -> in_out(0.2)

000.255 <- in_out(0.25)

000.309 <- in_out(0.2)

True

Scheduler.run()Note that because sb.run() had returned True, we could have inferred that all jobs have completed. As a matter of fact, run() returns True if and only if:

Note:

What happens if these two conditions are not met depends on the critical attribute on the scheduler object:

run() returns False;run() will raise an exception, depending on the reason behind the failure, see co_run() for details.This behaviour has been chosen so that nested schedulers do the right thing: it allows exceptions to bubble from inner schedulers up to the toplevel one, and to trigger its abrupt termination.

See also failed_critical(), failed_time_out(), debrief() and why().

Scheduler.list()Before we see more examples, let's see more ways to get information about what happened once run finishes.

For example to check that job b1 has completed:

print(b1.is_done())

True

To check that job b3 has not raised an exception:

print(b3.raised_exception())

None

To see an overview of a scheduler, just use the list() method that will summarize the contents of a scheduler:

sb.list()

1 ⚠ ☉ ☓ <Job `b1`> [[ -> 100.0]]

2 ⚠ ☉ ☓ <Job `b2`> [[ -> 200.0]] requires={1}

3 ⚠ ☉ ☓ <Job `Job[in_out (...)]`> [[ -> 250.0]]

The textual representation displayed by list() shows all the jobs, with:

list_safe())The individual lifecycle for a job instance is:

idle → scheduled → running → done

where the 'scheduled' state is for cases where a maximal number of simulataneous jobs has been reached - see jobs_window - so the job essentially has all its requirements fulfilled but still waits for its turn.

With that in mind, here is a complete list of the symbols used, with their meaning:

⚐ : idle (read: requirements are not fulfilled)⚑ : scheduled (read: waiting for a slot in the jobs window)↺ : running☓ : complete★ : raised an exception☉ : went through fine (no exception raised)⚠ : defined as critical∞ : defined as foreverAnd and here's an example of output for list() with all possible combinations of jobs:

01 ⚠ ⚐ ∞ <J `forever=True crit.=True status=idle boom=False`>

02 ⚠ ⚐ <J `forever=False crit.=True status=idle boom=False`> - requires {01}

03 ⚐ ∞ <J `forever=True crit.=False status=idle boom=False`> - requires {02}

04 ⚐ <J `forever=False crit.=False status=idle boom=False`> - requires {03}

05 ⚠ ⚑ ∞ <J `forever=True crit.=True status=scheduled boom=False`> - requires {04}

06 ⚠ ⚑ <J `forever=False crit.=True status=scheduled boom=False`> - requires {05}

07 ⚑ ∞ <J `forever=True crit.=False status=scheduled boom=False`> - requires {06}

08 ⚑ <J `forever=False crit.=False status=scheduled boom=False`> - requires {07}

09 ⚠ ☉ ↺ ∞ <J `forever=True crit.=True status=running boom=False`> - requires {08}

10 ⚠ ☉ ↺ <J `forever=False crit.=True status=running boom=False`> - requires {09}

11 ☉ ↺ ∞ <J `forever=True crit.=False status=running boom=False`> - requires {10}

12 ☉ ↺ <J `forever=False crit.=False status=running boom=False`> - requires {11}

13 ⚠ ★ ☓ ∞ <J `forever=True crit.=True status=done boom=True`>!! CRIT. EXC. => bool:True!! - requires {12}

14 ⚠ ★ ☓ <J `forever=False crit.=True status=done boom=True`>!! CRIT. EXC. => bool:True!! - requires {13}

15 ★ ☓ ∞ <J `forever=True crit.=False status=done boom=True`>!! exception => bool:True!! - requires {14}

16 ★ ☓ <J `forever=False crit.=False status=done boom=True`>!! exception => bool:True!! - requires {15}

17 ⚠ ☉ ☓ ∞ <J `forever=True crit.=True status=done boom=False`>[[ -> 0]] - requires {16}

18 ⚠ ☉ ☓ <J `forever=False crit.=True status=done boom=False`>[[ -> 0]] - requires {17}

19 ☉ ☓ ∞ <J `forever=True crit.=False status=done boom=False`>[[ -> 0]] - requires {18}

20 ☉ ☓ <J `forever=False crit.=False status=done boom=False`>[[ -> 0]] - requires {19}

Note that if your locale/terminal cannot output these, the code will tentatively resort to pure ASCII output.

It is easy to get a graphical representation of a scheduler. From inside a jupyter notebook, you would just need to do e.g.

sb2.graph()

However, in the context of readthedocs, this notebook is translated into a static markdown file, so we cannot use this elegant approach. Instead, we use a more rustic workflow, that first creates the graph as a dot file, and then uses an external tool to produce a png file:

# this can always be done, it does not require graphviz to be installed

sb2.export_as_dotfile("readme-example-b.dot")

'(Over)wrote readme-example-b.dot'

# assuming you have the 'dot' program installed (it ships with graphviz)

import os

os.system("dot -Tpng readme-example-b.dot -o readme-example-b.png")

0

We can now look at the result, where you can recognize the logic of example B:

Sometimes it is useful to deal with a endless loop; for example if we want to separate completely actions and printing, we can use an asyncio.Queue to implement a simple message bus as follows:

message_bus = asyncio.Queue()

async def monitor_loop(bus):

while True:

message = await bus.get()

print("BUS: {}".format(message))

Now we need a modified version of the in_out coroutine, that interacts with this message bus instead of printing anything itself :

async def in_out_bus(timeout, bus):

global watch

await bus.put("{} -> in_out({})".format(watch.elapsed(), timeout))

await asyncio.sleep(timeout)

await bus.put("{} <- in_out({})".format(watch.elapsed(), timeout))

# return something easy to recognize

return 10 * timeout

We can replay the prevous scenario, adding the monitoring loop as a separate job.

However, we need to declare this extra job with forever=True, so that the scheduler knows it does not have to wait for the monitoring loop, as we know in advance that this monitoring loop will, by design, never return.

c1, c2, c3, c4 = (Job(in_out_bus(0.2, message_bus), label="c1"),

Job(in_out_bus(0.4, message_bus), label="c2"),

Job(in_out_bus(0.3, message_bus), label="c3"),

Job(monitor_loop(message_bus), forever=True, label="monitor"))

c3.requires(c1)

watch.reset()

sc = Scheduler(c1, c2, c3, c4)

sc.run()

BUS: 000.000 -> in_out(0.2)

BUS: 000.000 -> in_out(0.4)

BUS: 000.205 <- in_out(0.2)

BUS: 000.206 -> in_out(0.3)

BUS: 000.406 <- in_out(0.4)

BUS: 000.509 <- in_out(0.3)

True

Note that run() always terminates as soon as all the non-forever jobs are complete. The forever jobs, on the other hand, get cancelled, so of course no return value is available at the end of the scenario :

sc.list()

1 ⚠ ☉ ☓ <Job `c1`> [[ -> 2.0]]

2 ⚠ ☉ ☓ <Job `c2`> [[ -> 4.0]]

3 ⚠ ☉ ☓ <Job `c3`> [[ -> 3.0]] requires={1}

4 ⚠ ☉ ↺ ∞ <Job `monitor`> [not done]

Forever jobs appear with a dotted border on a graphical representation:

# a function to materialize the rustic way of producing a graphical representation

def make_png(scheduler, prefix):

dotname = "{}.dot".format(prefix)

pngname = "{}.png".format(prefix)

scheduler.export_as_dotfile(dotname)

os.system("dot -Tpng {dotname} -o {pngname}".format(**locals()))

print(pngname)

make_png(sc, "readme-example-c")

readme-example-c.png

Note: a scheduler being essentially a set of jobs, the order of creation of jobs in the scheduler is not preserved in memory.

A Scheduler object has a timeout attribute, that can be set to a duration (in seconds). When provided, run() will ensure its global duration does not exceed this value, and will return False or raise TimeoutError if the timeout triggers.

Of course this can be used with any number of jobs and dependencies, but for the sake of simplicity let us see this in action with just one job that loops forever:

async def forever():

global watch

for i in range(100000):

print("{}: forever {}".format(watch.elapsed(), i))

await asyncio.sleep(.1)

j = Job(forever(), forever=True)

watch.reset()

sd = Scheduler(j, timeout=0.25, critical=False)

sd.run()

000.000: forever 0

000.104: forever 1

000.209: forever 2

11:34:57.169 SCHEDULER(None): PureScheduler.co_run: TIMEOUT occurred

False

As you can see the result of run() in this case is False, since not all jobs have completed. Apart from that the jobs is now in this state:

j

⚠ ☉ ↺ ∞ <Job `Job[forever (...)]`> [not done]

A job instance can be critical or not; what this means is as follows:

False;In both cases the exception can be retrieved in the corresponding Job object with raised_exception().

async def boom(n):

await asyncio.sleep(n)

raise Exception("boom after {}s".format(n))

# by default everything is non critical

e1 = Job(in_out(0.2), label='begin')

e2 = Job(boom(0.2), label="boom", critical=False)

e3 = Job(in_out(0.3), label='end')

se = Scheduler(Sequence(e1, e2, e3), critical=False)

# with these settings, jobs 'end' is not hindered

# by the middle job raising an exception

watch.reset()

se.run()

000.000 -> in_out(0.2)

000.205 <- in_out(0.2)

000.409 -> in_out(0.3)

000.710 <- in_out(0.3)

True

# in this listing you can see that job 'end'

# has been running and has returned '300' as expected

se.list()

1 ⚠ ☉ ☓ <Job `begin`> [[ -> 200.0]]

2 ★ ☓ <Job `boom`> !! exception => Exception:boom after 0.2s!! requires={1}

3 ⚠ ☉ ☓ <Job `end`> [[ -> 300.0]] requires={2}

Non-critical jobs and schedulers show up with a thin and black border:

make_png(se, "readme-example-e")

readme-example-e.png

Making the boom job critical would instead cause the scheduler to bail out:

f1 = Job(in_out(0.2), label="begin")

f2 = Job(boom(0.2), label="boom", critical=True)

f3 = Job(in_out(0.3), label="end")

sf = Scheduler(Sequence(f1, f2, f3), critical=False)

# with this setup, orchestration stops immediately

# when the exception triggers in boom()

# and the last job does not run at all

watch.reset()

sf.run()

000.000 -> in_out(0.2)

000.202 <- in_out(0.2)

11:34:58.383 SCHEDULER(None): Emergency exit upon exception in critical job

False

# as you can see, job 'end' has not even started here

sf.list()

1 ⚠ ☉ ☓ <Job `begin`> [[ -> 200.0]]

2 ⚠ ★ ☓ <Job `boom`> !! CRIT. EXC. => Exception:boom after 0.2s!! requires={1}

3 ⚠ ⚐ <Job `end`> [not done] requires={2}

Critical jobs and schedulers show up with a thick and red border:

make_png(sf, "readme-example-f")

readme-example-f.png

A Scheduler has a jobs_window attribute that allows to specify a maximum number of jobs running simultaneously.

When jobs_windows is not specified or 0, it means no limit is imposed on the running jobs.

# let's define a simple coroutine

async def aprint(message, delay=0.5):

print(message)

await asyncio.sleep(delay)

# let us now add 8 jobs that take 0.5 second each

s = Scheduler(jobs_window=4)

for i in range(1, 9):

s.add(Job(aprint("{} {}-th job".format(watch.elapsed(), i), 0.5)))

# so running them with a window of 4 means approx. 1 second

watch.reset()

s.run()

# expect around 1 second

print("total duration = {}s".format(watch.elapsed()))

000.469 1-th job

000.469 2-th job

000.469 3-th job

000.469 4-th job

000.469 5-th job

000.469 6-th job

000.469 7-th job

000.469 8-th job

total duration = 001.004s

As mentioned in the introduction, a Scheduler instance can itself be used as a job. This makes it easy to split complex scenarii into pieces, and to combine them in a modular way.

Let us consider the following example:

# we start with the creation of an internal scheduler

# that has a simple diamond structure

sub_sched = Scheduler(label="critical nested", critical=True)

subj1 = Job(aprint("subj1"), label='subj1', scheduler=sub_sched)

subj2 = Job(aprint("subj2"), label='subj2', required=subj1, scheduler=sub_sched)

subj3 = Job(aprint("subj3"), label='subj3', required=subj1, scheduler=sub_sched)

subj4 = Job(aprint("subj4"), label='subj4', required=(subj2, subj3), scheduler=sub_sched)

make_png(sub_sched, "readme-subscheduler")

readme-subscheduler.png

We can now create a main scheduler, in which one of the jobs is this low-level scheduler:

# the main scheduler

main_sched = Scheduler(

Sequence(

Job(aprint("main-start"), label="main-start"),

# the way to graft the low-level logic in this main workflow

# is to just use the ShcdulerJob instance as a job

sub_sched,

Job(aprint("main-end"), label="main-end"),

)

)

This nested structure is rendered by both list() and graph():

# list() shows the contents of sub-schedulers implemented as Scheduler instances

main_sched.list()

1 ⚠ ⚐ <Job `main-start`> [not done]

2 ⚠ ⚐ <Scheduler `critical nested`> [not done] requires={1} -> entries={3}

3 ⚠ ⚐ > <Job `subj1`> [not done]

4 ⚠ ⚐ > <Job `subj2`> [not done] requires={3}

5 ⚠ ⚐ > <Job `subj3`> [not done] requires={3}

6 ⚠ ⚐ > <Job `subj4`> [not done] requires={4, 5}

2 --end-- < <Scheduler `critical nested`> exits={6}

7 ⚠ ⚐ <Job `main-end`> [not done] requires={2}

When using a Scheduler to describe nested schedulers, asynciojobs will also produce a graphical output that properly exhibits the overall structure:

Let us do this again another way, so that this shows up properly in readthedocs:

make_png(main_sched, "readme-nested")

readme-nested.png

Here's how the main scheduler would be rendered by graph():

Which when executed produces this output:

main_sched.run()

main-start

subj1

subj2

subj3

subj4

main-end

True

This feature can can come in handy to deal with issues like:

you want to be able to re-use code - as in writing a library - and nesting schedulers is a convenient way to address that; functions can return pieces of workflows implemented as schedulers, that can be easily mixed within a larger scenario;

in another dimension, nested schedulers can be a solution if

jobs_window attribute to apply to only a subset of your jobs;timeout attribute to apply to only a subset of your jobs;forever jobs that need to be terminated sooner than the very end of the overall scenario.Internally, asynciojobs comes with the PureScheduler class.

A PureScheduler instance is a fully functional scheduler, but it cannot be used as a nested scheduler.

In terms of implementation, Scheduler is a mixin class that inherits from both PureScheduler and AbstractJob.

In previous versions of this library, the Scheduler class could not be nested, and a specific class was required for the purpose of creating nestable schedulers, like is shown in this table:

| version | just scheduling | nestable scheduler |

|---|---|---|

| <= 0.8 | Scheduler | no class available |

| == 0.9 | Scheduler | SchedulerJob |

| >= 0.10 | PureScheduler | Scheduler |

The bottom line is that, starting with version 0.10, users primarily do not need to worry about that, and creating only nestable Scheduler objects is the recommended approach.

Scheduler classScheduler.debrief()Scheduler.debrief() is designed for schedulers that have run and returned False, it does output the same listing as list() but with additional statistics on the number of jobs, and, most importantly, on the stacks of jobs that have raised an exception.

Scheduler.sanitize()In some cases like esp. test scenarios, it can be helpful to add requirements to jobs that are not in the scheduler. The sanitize method removes such extra requirements, and unless you are certain it is not your case, it might be a good idea to call it explcitly before an orchestration.

Scheduler.check_cycles()check_cycles will check for cycles in the requirements graph. It returns a boolean. It's a good idea to call it before running an orchestration.

Scheduler.co_run()run() is a regular def function (i.e. not an async def), but in fact just a wrapper around the native coroutine called co_run().

def run(self, *args, **kwds):

loop = asyncio.get_event_loop()

return loop.run_until_complete(self.co_run(*args, **kwds))

shutdown() method.Scheduler objects expose the shutdown() method.

This method should be called explicitly by the user when resources are attached to the various jobs, and they can be released.

Contrary to what was done in older versions of asynciojobs, where nested schedulers were not yet as massively useful, this call needs to be explicit, it is no longer automatically invoked by run() when the orchestration is over.

Although such a cleanup is not really useful in the case of local Job instances, some application libraries like apssh define jobs that are attached to network connections, ssh connections in the case of apssh, and it is convenient to be able to terminate those connections explicitly.

Scheduler.graph()If you have the graphviz package installed, you can inspect a scheduler instance in a Jupyter notebook by using the graph() method, that returns a graphviz.Digraph instance; this way the scheduler graph can be displayed interactively in a notebook - see also http://graphviz.readthedocs.io/en/stable/manual.html#jupyter-notebooks.

Here's a simple example:

# and a simple scheduler with an initialization and 2 concurrent tasks

s = Scheduler()

j1 = Job(aprint("j1"), label="init", critical=False, scheduler=s)

j2 = Job(aprint("j2"), label="critical job", critical=True, scheduler=s, required=j1)

j3 = Job(aprint("j3"), label="forever job", critical=False, forever=True, scheduler=s, required=j1)

s.graph()

In a regular notebook, that is all you need to do to see the scheduler's graph.

In the case of this README though, once rendered on readthedocs.io the graph has got lost in translation, so please read on to see that graph.

Scheduler.export_as_dotfile()If visualizing in a notebook is not an option, or if you do not have graphviz installed, you can still produce a dotfile from a scheduler object:

s.export_as_dotfile('readme-dotfile.dot')

'(Over)wrote readme-dotfile.dot'

Then later on - and possibly on another host - you can use this dot file as an input to produce a .png graphics, using the dot program (which is part of graphviz), like e.g.:

import os

os.system("dot -Tpng readme-dotfile.dot -o readme-dotfile.png")

0

Which now allows us to render the graph for our last scheduler as a png file:

Legend: on this small example we can see that:

Although this is not illustrated here, the same graphical legend is applicable to nested schedulers as well.

Note that if you do have graphviz available, you can produce a png file a little more simply, i.e. without the need for creating the dot file, like this:

# a trick to produce a png file on a box that has graphviz pip-installed

g = s.graph()

g.format = 'png'

g.render('readme')

'readme.png'

As a general rule, and maybe especially when dealing with nested schedulers, it is important to keep in mind the following constraints.

One given job should be inserted in exactly one scheduler. Be aware that the code does not check for this, it is the programmer's responsability to enforce this rule.

A job that is not inserted in any scheduler will of course never be run.

A job inserted in several schedulers will most likely behave very oddly, as each scheduler will be in a position to have it move along.

With nested schedulers, it can be tempting to create dependencies between jobs that are not part of the same scheduler, but that belong in sibling or cousin schedulers.

This is currently not supported, a job can only have requirements to other jobs in the same scheduler.

Like for the previous topic, as of now there is no provision in the code to enforce that, and failing to comply with that rule will result in unexpected behaviour.

Another common mistake is to try and reuse a job instance in several places in a scheduler. Each instance carries the state of the job progress, so it is important to create as many instances/copies as there are tasks, and to not try and share job objects.

In particular, if you take one job instance that has completed, and try to insert it into a new scheduler, it will be considered as done, and will not run again.

In much the same way, once a scheduler is done - assuming all went well - essentially all of its jobs are marked as done, and trying to run it again will either do nothing, or raise an exception.

Job classJob actually is a specializtion of AbstractJob, and the specification is that the co_run() method should denote a coroutine itself, as that is what is triggered by Scheduler when running said job.

AbstractJob.co_shutdown()The shutdown() method on a scheduler sends co_shutdown() method on all - possibly nested - jobs. The default behaviour - in the Job class - is to do nothing, but this can be redefined by daughter classes of AbstractJob when relevant. Typically, an implementation of an SshJob will allow for a given SSH connection to be shared amongst several SshJob instances, and so co_shutdown() may be used to close the underlying SSH connections.

apssh library and the SshJob classYou can easily define your own Job class by specializing job.AbstractJob. As an example, which was the primary target when developping asynciojobs, you can find in the apssh library a SshJob class, with which you can easily orchestrate scenarios involving several hosts that you interact with using ssh.

FAQs

A simplistic orchestration engine for asyncio-based jobs

We found that asynciojobs demonstrated a healthy version release cadence and project activity because the last version was released less than a year ago. It has 1 open source maintainer collaborating on the project.

Did you know?

Socket for GitHub automatically highlights issues in each pull request and monitors the health of all your open source dependencies. Discover the contents of your packages and block harmful activity before you install or update your dependencies.

Security News

Research

The Socket Research Team breaks down a malicious wrapper package that uses obfuscation to harvest credentials and exfiltrate sensitive data.

Research

Security News

Attackers used a malicious npm package typosquatting a popular ESLint plugin to steal sensitive data, execute commands, and exploit developer systems.

Security News

The Ultralytics' PyPI Package was compromised four times in one weekend through GitHub Actions cache poisoning and failure to rotate previously compromised API tokens.