Security News

Research

Data Theft Repackaged: A Case Study in Malicious Wrapper Packages on npm

The Socket Research Team breaks down a malicious wrapper package that uses obfuscation to harvest credentials and exfiltrate sensitive data.

Yasha is a code generator based on Jinja2 template engine. At its simplest, a command-line call

yasha -v variables.yaml template.txt.j2

will render template.txt.j2 into a new file named as template.txt. See how the created file name is derived from the template name. The template itself remains unchanged.

The tool was originally written to generate code for the zinc.rs' I/O register interface from the CMSIS-SVD description file, and was used to interface with the peripherals of Nordic nRF51 ARM Cortex-M processor-based microcontroller. Yasha has since evolved to be flexible enough to be used in any project where the code generation is needed. The tool allows extending Jinja by domain specific filters, tests and extensions, and it operates smoothly with the commonly used build automation software like Make, CMake and SCons.

As a regular user:

pip install yasha

or if you like to get the latest development version:

pip install git+https://github.com/kblomqvist/yasha.git

or if you would like to take part into the development process:

git clone https://github.com/kblomqvist/yasha.git

pip install -e yasha

Usage: yasha [OPTIONS] [TEMPLATE_VARIABLES]... TEMPLATE

Reads the given Jinja TEMPLATE and renders its content into a new file.

For example, a template called 'foo.c.j2' will be written into 'foo.c' in

case the output file is not explicitly given.

Template variables can be defined in a separate file or given as part of

the command-line call, e.g.

yasha --hello=world -o output.txt template.j2

defines a variable 'hello' for a template like:

Hello {{ hello }} !

Options:

-o, --output FILENAME Place the rendered template into FILENAME.

-v, --variables FILENAME Read template variables from FILENAME. Built-

in parsers are JSON, YAML, TOML, INI, XML and CSV.

-e, --extensions FILENAME Read template extensions from FILENAME. A

Python file is expected.

-c, --encoding TEXT Default is UTF-8.

-I, --include_path DIRECTORY Add DIRECTORY to the list of directories to be

searched for the referenced templates.

--no-variable-file Omit template variable file.

--no-extension-file Omit template extension file.

--no-trim-blocks Load Jinja with trim_blocks=False.

--no-lstrip-blocks Load Jinja with lstrip_blocks=False.

--remove-trailing-newline Load Jinja with keep_trailing_newline=False.

--mode [pedantic|debug] In pedantic mode Yasha becomes extremely picky

on templates, e.g. undefined variables will

raise an error. In debug mode undefined

variables will print as is.

-M Outputs Makefile compatible list of

dependencies. Doesn't render the template.

-MD Creates Makefile compatible .d file alongside

the rendered template.

--version Print version and exit.

-h, --help Show this message and exit.

Template variables can be defined in a separate file. By default JSON, YAML, TOML, INI, XML and CSV formats are supported.

yasha -v variables.yaml template.j2

In case multiple files are given, the variables redefined in later files will take precedence.

yasha -v variables.yaml -v additional_variables.yaml template.j2

Additionally you may define variables as part of the command-line call. A variable defined via command-line will overwrite a variable defined in a file.

yasha --foo=bar -v variables.yaml template.j2

to use the data stored in a csv variable file in templates, the name of the variable in the template has to match the name of the csv variable file.

For example, consider the following template and variable files

template.j2

mydata.csv

And the following contents in mydata.csv

cell1,cell2,cell3

cell4,cell5,cell6

to access the rows of cells, you use the following syntax in your template (note that 'mydata' here matches the file name of the csv file)

{% for row in mydata %}

cell 1's value is {{row[0]}},

cell 2's value is {{row[1]}}

{% endfor %}

By default, each row in the csv file is accessed in the template as a list of values (row[0], row[1], etc).

You can make each row accessible instead as a mapping by adding a header to the csv file.

For example, consider the following contents of mydata.csv

first_column,column2,third column

cell1,cell2,cell3

cell4,cell5,cell6

and the following Jinja template

{% for row in mydata %}

cell 1's value is {{row.first_column}},

cell 2's value is {{row.column2}},

cell 3's value is {{row['third column']}}

{% endfor %}

As you can see, cells can be accessed by column name instead of column index.

If the column name has no spaces in it, the cell can be accessed with 'dotted notation' (ie row.first_column) or 'square-bracket notation' (ie row['third column'].

If the column name has a space in it, the cell can only be accessed with 'square-bracket notation'

If no variable file is explicitly given, Yasha will look for one by searching for a file named in the same way than the corresponding template but with the file extension either .json, .yaml, .yml, .toml, or .xml.

For example, consider the following template and variable files

template.j2

template.yaml

Because of automatic file variables look up, the command-line call

yasha template.j2

is equal to

yasha -v template.yaml template.j2

In case you want to omit the file variables in spite of its existence, use --no-variable-file option flag.

Imagine that you would be writing C code and have the following two templates in two different folders

root/

include/foo.h.j2

source/foo.c.j2

and you would like to share the same file variables between these two templates. So instead of creating separate foo.h.yaml and foo.c.yaml you can create foo.yaml under the root folder:

root/

include/foo.h.j2

source/foo.c.j2

foo.yaml

Now when you call

cd root

yasha include/foo.h.j2

yasha source/foo.c.j2

the variables defined in foo.yaml are used within both templates. This works because subfolders will be checked for the variable file until the current working directory is reached — root in this case. For instance, variables are looked for foo.h.j2 in following order:

include/foo.h.yaml

include/foo.yaml

foo.h.yaml

foo.yaml

You can extend Yasha by custom Jinja extensions, tests and filters by defining those in a separate Python source file given via command-line option -e, or --extensions as shown below

yasha -e extensions.py -v variables.yaml template.j2

Like for variable file, Yasha supports automatic extension file look up and sharing too. To avoid file collisions consider using the following naming convention for your template, extension, and variable files:

template.py.j2

template.py.py

template.py.yaml

Now the command-line call

yasha template.py.j2

is equal to

yasha -e template.py.py -v template.py.yaml template.py.j2

Functions intended to work as a test have to be either prefixed by test_

def test_even(number):

return number % 2 == 0

of defined in TESTS dictionary

def is_even(number):

return number % 2 == 0

TESTS = {

'even': is_even,

}

Functions intended to work as a filter have to be either prefixed by filter_

def filter_replace(s, old, new):

return s.replace(old, new)

or defined in FILTERS dictionary

def do_replace(s, old, new):

return s.replace(old, new)

FILTERS = {

'replace': do_replace,

}

All classes derived from jinja2.ext.Extension are considered as Jinja extensions and will be added to the environment used to render the template.

If none of the built-in parsers fit into your needs, it's possible to declare your own parser within the extension file. Either create a function named as parse_ + <file extension>, or define the parse-function in PARSERS dictionary with the key indicating the file extension. Yasha will then pass the variable file object for the function to be parsed and expects to get dictionary as a return value.

For example, below is shown an example XML file and a custom parser for that.

<!-- variables.xml -->

<persons>

<person>

<name>Foo</name>

<address>Foo Valley</address>

</person>

<person>

<name>Bar</name>

<address>Bar Valley</address>

</person>

</persons>

# extensions.py

import xml.etree.ElementTree as et

def parse_xml(file):

assert file.name.endswith('.xml')

tree = et.parse(file.name)

root = tree.getroot()

persons = []

for elem in root.iter('person'):

persons.append({

'name': elem.find('name').text,

'address': elem.find('address').text,

})

return dict(persons=persons)

You may change the template syntax via file extensions by redefining the Jinja parser / lexer. The example below mimics the LaTeX environment.

# extensions.py

BLOCK_START_STRING = '<%'

BLOCK_END_STRING = '%>'

VARIABLE_START_STRING = '<<'

VARIABLE_END_STRING = '>>'

COMMENT_START_STRING = '<#'

COMMENT_END_STRING = '#>'

Reads system environment variable in a template like

sqlalchemy:

url: {{ 'POSTGRES_URL' | env }}

Params: default=None

Allows to spawn new processes and connect to their standard output. The output is decoded and stripped by default.

os:

type: {{ "lsb_release -a | grep Distributor | awk '{print $3}'" | shell }}

version: {{ 'cat /etc/debian_version' | shell }}

os:

type: Debian

version: 9.1

Requires: Python >= 3.5

Params: strip=True, check=True, timeout=2

Allows to spawn new processes, but unlike shell behaves like Python's standard library.

{% set r = "uname" | subprocess(check=False) %}

{# Returns either CompletedPorcess or CalledProcessError instance #}

{% if r.returncode -%}

platform: Unknown

{% else -%}

platform: {{ r.stdout.decode() }}

{%- endif %}

platform: Linux

Requires: Python >= 3.5

Params: stdout=True, stderr=True, check=True, timeout=2

Yasha can render templates from STDIN to STDOUT. For example, the below command-line call will render template from STDIN to STDOUT.

cat template.j2 | yasha -v variables.yaml -

Variables given as part of the command-line call can be Python literals, e.g. a list would be defined like this

yasha --lst="['foo', 'bar', 'baz']" template.j2

The following is also interpreted as a list

yasha --lst=foo,bar,baz template.j2

Note that in case you like to pass a string with commas as a variable you have to quote it as

yasha --str='"foo,bar,baz"' template.j2

Other possible literals are:

-1, 0, 1, 2 (an integer)2+3j, 0+5j (a complex number)3.5, -2.7 (a float)(1,), (1, 2) (a tuple){'a': 2} (a dict){1, 2, 3} (a set)True, False (boolean)Sometimes it would make sense to have common extensions over multiple templates, e.g. for the sake of filters. This can be achieved by setting YASHA_EXTENSIONS environment variable.

export YASHA_EXTENSIONS=$HOME/.yasha/extensions.py

yasha -v variables.yaml -o output.txt template.j2

By default the referenced templates, i.e. files referred to via Jinja's extends, include or import statements, are searched in relation to the template location. To extend the search path you can use the command-line option -I — like you would do with GCC to include C header files.

yasha -v variables.yaml -I $HOME/.yasha template.j2

{% extends "skeleton.j2" %}

{# 'skeleton.j2' is searched also from $HOME/.yasha #}

{% block main %}

{{ super() }}

...

{% endblock %}

If you need to pre-process template variables before those are passed into the template, you can do that via file extensions by wrapping the built-in parsers.

# extensions.py

from yasha.parsers import PARSERS

def wrapper(parse):

def postprocess(file):

variables = parse(file)

variables['foo'] = 'bar' # foo should always be bar

return variables

return postprocess

for name, function in PARSERS.items():

PARSERS[name] = wrapper(function)

Ansible is an IT automation platform that makes your applications and systems easier to deploy. It is based on Jinja2 and offers a large set of custom tests and filters, which can be easily taken into use via Yasha's file extensions.

pip install ansible

# extensions.py

from ansible.plugins.test.core import TestModule

from ansible.plugins.filter.core import FilterModule

FILTERS = FilterModule().filters()

FILTERS.update(TestModule().tests()) # Ansible tests are filter like

For security reasons, the built-in YAML parser is using the safe_load of PyYaml. This limits variables to simple Python objects like integers or lists. To work with a Python object of any type, you can overwrite the built-in implementation of the parser.

# extensions.py

import yaml

def parse_yaml(file):

assert file.name.endswith(('.yaml', '.yml'))

variables = yaml.load(file)

return variables if variables else dict()

def parse_yml(file):

return parse_yaml(file)

Yasha command-line options -M and -MD return the list of the template dependencies in a Makefile compatible format. The later creates the separate .d file alongside the template rendering instead of printing to stdout. These options allow integration with the build automation tools. Below are given examples for C files using CMake, Make and SCons.

# CMakeList.txt

cmake_minimum_required(VERSION 2.8.7)

project(yasha)

file(GLOB sources "src/*.c")

file(GLOB templates "src/*.jinja")

foreach(template ${templates})

string(REGEX REPLACE "\\.[^.]*$" "" output ${template})

execute_process(

COMMAND yasha -M ${template}

WORKING_DIRECTORY ${CMAKE_SOURCE_DIR}

OUTPUT_VARIABLE deps

)

string(REGEX REPLACE "^.*: " "" deps ${deps})

string(REPLACE " " ";" deps ${deps})

add_custom_command(

OUTPUT ${output}

COMMAND yasha -o ${output} ${template}

DEPENDS ${deps}

)

list(APPEND sources ${output})

endforeach()

add_executable(a.out ${sources})

# Makefile

# User variables

SOURCES = $(wildcard src/*.c)

TEMPLATES = $(wildcard src/*.jinja)

EXECUTABLE = build/a.out

# Add rendered .c templates to sources list

SOURCES += $(filter %.c, $(basename $(TEMPLATES)))

# Resolve build dir from executable

BUILDDIR = $(dir $(EXECUTABLE))

# Resolve object files

OBJECTS = $(addprefix $(BUILDDIR), $(SOURCES:.c=.o))

# Resolve .d files which list what files the object

# and template files depend on

OBJECTS_D = $(OBJECTS:.o=.d)

TEMPLATES_D = $(addsuffix .d,$(basename $(TEMPLATES)))

$(EXECUTABLE) : $(OBJECTS)

$(CC) $^ -o $@

$(BUILDDIR)%.o : %.c | $(filter %.h, $(basename $(TEMPLATES)))

@mkdir -p $(dir $@)

$(CC) -MMD -MP $< -c -o $@

%.c : %.c.jinja

yasha -MD $< -o $@

%.h : %.h.jinja

yasha -MD $< -o $@

# Make sure that the following built-in implicit rule is cancelled

%.o : %.c

# Pull in dependency info for existing .o and template files

-include $(OBJECTS_D) $(TEMPLATES_D)

# Prevent Make to consider rendered templates as intermediate file

.secondary : $(basename $(TEMPLATES))

clean :

ifeq ($(BUILDDIR),./)

-rm -f $(EXECUTABLE)

-rm -f $(OBJECTS)

-rm -f $(OBJECTS_D)

else

-rm -rf $(BUILDDIR)

endif

-rm -f $(TEMPLATES_D)

-rm -f $(basename $(TEMPLATES))

.phony : clean

# SConstruct

import os

import yasha.scons

env = Environment(

ENV = os.environ,

BUILDERS = {"Yasha": yasha.scons.CBuilder()}

)

sources = ["main.c"]

sources += env.Yasha(["foo.c.jinja", "foo.h.jinja"]) # foo.h not appended to sources

env.Program("a.out", sources)

Another example with separate build and src directories.

# SConstruct

import os

import yasha.scons

env = Environment(

ENV = os.environ,

BUILDERS = {"Yasha": yasha.scons.CBuilder()}

)

sources = ["build/main.c"]

duplicate = 0 # See how the duplication affects to the file paths

env.VariantDir("build", "src", duplicate=duplicate)

if duplicate:

tmpl = ["build/foo.c.jinja", "build/foo.h.jinja"]

sources += env.Yasha(tmpl)

else:

tmpl = ["src/foo.c.jinja", "src/foo.h.jinja"]

sources += env.Yasha(tmpl)

env.Program("build/a.out", sources)

FAQs

A command-line tool to render Jinja templates

We found that yasha demonstrated a healthy version release cadence and project activity because the last version was released less than a year ago. It has 1 open source maintainer collaborating on the project.

Did you know?

Socket for GitHub automatically highlights issues in each pull request and monitors the health of all your open source dependencies. Discover the contents of your packages and block harmful activity before you install or update your dependencies.

Security News

Research

The Socket Research Team breaks down a malicious wrapper package that uses obfuscation to harvest credentials and exfiltrate sensitive data.

Research

Security News

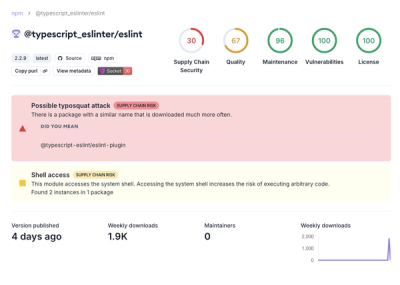

Attackers used a malicious npm package typosquatting a popular ESLint plugin to steal sensitive data, execute commands, and exploit developer systems.

Security News

The Ultralytics' PyPI Package was compromised four times in one weekend through GitHub Actions cache poisoning and failure to rotate previously compromised API tokens.