Security News

Research

Data Theft Repackaged: A Case Study in Malicious Wrapper Packages on npm

The Socket Research Team breaks down a malicious wrapper package that uses obfuscation to harvest credentials and exfiltrate sensitive data.

protoduck is a JavaScript library is a

library for making groups of methods, called "protocols", that work together to

provide some abstract functionality that other things can then rely on. If

you're familiar with the concept of "duck

typing", then it might make sense to

think of protocols as things that explicitly define what methods you need in

order to "clearly be a duck".

On top of providing a nice, clear interface for defining these protocols, this module clear, useful errors when implementations are missing something or doing something wrong.

One thing that sets this library apart from others is that on top of defining

duck-typed protocols on a single class/type, it lets you have different

implementations depending on the arguments. So a method on Foo may call

different code dependent on whether its first argument is Bar or Baz. If

you've ever wished a method worked differently for different types of things

passed to it, this does that!

$ npm install protoduck

import protocol from "protoduck"

// Quackable is a protocol that defines three methods

const Quackable = protocol({

walk: [],

talk: [],

isADuck: [() => true] // default implementation -- it's optional!

})

// `duck` must implement `Quackable` for this function to work. It doesn't

// matter what type or class duck is, as long as it implements Quackable.

function doStuffToDucks (duck) {

if (!duck.isADuck()) {

throw new Error('I want a duck!')

} else {

console.log(duck.walk())

console.log(duck.talk())

}

}

// and another place...

class Duck () {}

// Implement the protocol on the Duck class.

Quackable(Duck, [], {

walk() { return "*hobble hobble*" }

talk() { return "QUACK QUACK" }

})

// main.js

doStuffToDucks(new Duck()) // works!

this (multimethods)JavaScript comes with its own method definition mechanism: You simply add

regular functions as properties to regular objects, and when you do

obj.method(), it calls the right code! ES6/ES2015 further extended this by

adding a class syntax that allowed this same system to work with more familiar

syntax sugar: class Foo { method() { ... } }.

protoduck is a similar language extension: it adds something called

"protocols" to JavaScript.

The purpose of protocols is to have a more explicit definitions of what methods "go together". That is, if you have a type of task, you can group every method that things definitely need to have under a protocol, and then write your code using the methods defined there. The assumption is that anything that defines that group of methods will work with the rest of your code.

And then you can export the protocol itself, and tell your users "if you implement this protocol for your own objects, they'll work with my code."

Duck typing is a common term for this: If it walks like a duck, and it talks like a duck, then it may as well be a duck, as far as any of our code is concerned.

The first step to using protoduck is to define a protocol. Protocol

definitions look like this:

// import the library first!

import protocol from "protoduck"

// `Ducklike` is the name of our protocol. It defines what it means for

// something to be "like a duck", as far as our code is concerned.

const Ducklike = protocol([], {

walk: [], // This says that the protocol requires a "walk" method.

talk: [] // and ducks also need to talk

peck: [] // and they can even be pretty scary

})

Protocols by themselves don't really do anything, they simply define what methods are included in the protocol, and thus what will need to be implemented.

The simplest type of definitions for protocols are as regular methods. In this

style, protocols end up working exactly like normal JavaScript methods: they're

added as properties of the target type/object, and we call them using the

foo.method() syntax. this is accessible inside the methods, as usual.

Implementation syntax is very similar to protocol definitions, but it calls the

protocol itself, instead of protocol. It also refers to the type that you want

to implement it on:

class Dog {}

// Implementing `Ducklike` for `Dog`s

Ducklike(Dog, [], {

walk() { return '*pads on all fours*' }

talk() { return 'woof woof. I mean "quack" >_>' }

peck(victim) { return 'Can I just bite ' + victim + ' instead?...' }

})

So now, our Dog class has two extra methods: walk, and talk, and we can

just call them:

const pupper = new Dog()

pupper.walk() // *pads on all fours*

pupper.talk() // woof woof. I mean "quack" >_>

pupper.peck('this string') // Can I just bite this string instead?...

You may have noticed before that we have these [] in various places that don't

seem to have any obvious purpose.

These arrays allow protocols to be implemented not just for a single value of

this, but across all arguments. That is, you can have methods in these

protocols that use both this, and the first argument (or any other arguments)

in order to determine what code to actually execute.

This type of method is called a multimethod, and isn't a core JavaScript

feature. It's something that sets protoduck apart, and it can be really

useful!

The way to use it is simple: in the protocol definitions, you put matching strings in different spots where those empty arrays were, and when you implement the protocol, you give the definition the actual types/objects you want to implement it on, and it takes care of mapping types to the strings you defined, and making sure the right code is run:

const Playable = protocol(['friend'], {

playWith: ['friend']

})

class Cat {}

class Human {}

class Dog {}

// The first protocol is for Cat/Human combination

Playable(Cat, [Human], {

playWith(human) {

return '*headbutt* *purr* *cuddle* omg ilu, ' + human.name

}

})

// And we define it *again* for a different combination

Playable(Cat, [Dog], {

playWith(dog) {

return '*scratches* *hisses* omg i h8 u, ' + dog.name

}

})

// depending on what you call it with, it runs different methods:

const cat = new Cat()

const human = new Human()

const dog = new Dog()

cat.playWith(human) // *headbutt* *purr* *cuddle* omg ilu, Sam

cat.playWith(dog) // *scratches* *hisses* omg i h8 u, Pupper

In general, most implementations you write won't care what types their arguments are, but when you do? This may end up saving you a lot of trouble and allowing some tricks you might realize you can do that weren't possible before!

Finally, there's a type of protocol impl that doesn't involve a this value at

all: static impls. Some languages might call them "class methods" as well. In

the case of protoduck, though, these static methods exist on the protocol

object itself, rather than a regular JavaScript class.

Static methods can be really useful when you want to call them as plain old

functions without having to worry about the this value. And because

protoduck supports multiple dispatch, it means you can get full method

functionality, but with regular functions that don't need this: they just

operate on their standard arguments.

Static impls are easy to make: simply omit the first object type and use the arguments array to define what the methods will be implemented on:

const Eq = protocol(['a', 'b'], {

equals: ['a', 'b']

})

const equals = Eq.equals // This isn't necessary, but it shows that we

// don't need a `.` to call them, at all!

Eq([Number, Number], {

equals(x, y) {

return x === y

}

})

Eq([Cat, Cat], {

equals(kitty, cat) {

return kitty.name === cat.name

}

})

equals(1, 1) // true

equals(1, 2) // false

equals(snookums, reika) // false

equals(walter, walter) // true

equals(1, snookums) // Error! No protocol impl!

protocol(<types>?, <spec>)Defines a new protocol on across arguments of types defined by <types>, which

will expect implementations for the functions specified in <spec>.

If <types> is missing, it will be treated the same as if it were an empty

array.

The types in <spec> must map, by string name, to the type names specified in

<types>, or be an empty array if <types> is omitted. The types in <spec>

will then be used to map between method implementations for the individual

functions, and the provided types in the impl.

const Eq = protocol(['a', 'b'], {

eq: ['a', 'b']

})

proto(<target>?, <types>?, <implementations>)Adds a new implementation to the given proto across <types>.

<implementations> must be an object with functions matching the protocol's

API. The types in <types> will be used for defining specific methods using

the function as the body.

Protocol implementations must include either <target>, <types>, or both:

If only <target> is present, implementations will be defined the same as

"traditional" methods -- that is, the definitions in <implementations>

will add function properties directly to <target>.

If only <types> is present, the protocol will keep all protocol functions as

"static" methods on the protocol itself.

If both are specified, protocol implementations will add methods to the <target>, and define multimethods using <types>.

If a protocol is derivable -- that is, all its functions have default impls,

then the <implementations> object can be omitted entirely, and the protocol

will be automatically derived for the given <types>

import protocol from '@zkat/protocols'

// Singly-dispatched protocols

const Show = protocol({

show: []

})

class Foo {}

Show(Foo, {

show () { return `[object Foo(${this.name})]` }

})

var f = new Foo()

f.name = 'alex'

f.show() === '[object Foo(alex)]'

import protocol from '@zkat/protocols'

// Multi-dispatched protocols

const Comparable = protocol(['target'], {

compare: ['target'],

})

class Foo {}

class Bar {}

class Baz {}

Comparable(Foo, [Bar], {

compare (bar) { return 'bars are ok' }

})

Comparable(Foo, [Baz], {

compare (baz) { return 'but bazzes are better' }

})

const foo = new Foo()

const bar = new Bar()

const baz = new Baz()

foo.compare(bar) // 'bars are ok'

foo.compare(baz) // 'but bazzes are better'

FAQs

Fancy duck typing for the most serious of ducks.

The npm package protoduck receives a total of 372,755 weekly downloads. As such, protoduck popularity was classified as popular.

We found that protoduck demonstrated a not healthy version release cadence and project activity because the last version was released a year ago. It has 1 open source maintainer collaborating on the project.

Did you know?

Socket for GitHub automatically highlights issues in each pull request and monitors the health of all your open source dependencies. Discover the contents of your packages and block harmful activity before you install or update your dependencies.

Security News

Research

The Socket Research Team breaks down a malicious wrapper package that uses obfuscation to harvest credentials and exfiltrate sensitive data.

Research

Security News

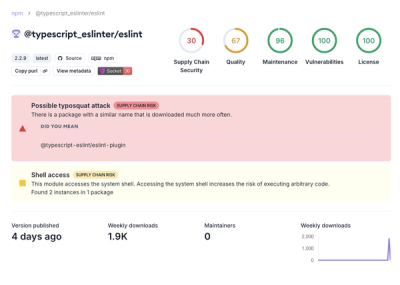

Attackers used a malicious npm package typosquatting a popular ESLint plugin to steal sensitive data, execute commands, and exploit developer systems.

Security News

The Ultralytics' PyPI Package was compromised four times in one weekend through GitHub Actions cache poisoning and failure to rotate previously compromised API tokens.