Security News

Research

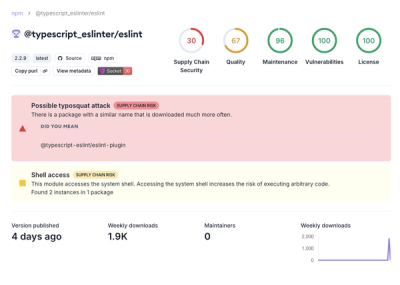

Data Theft Repackaged: A Case Study in Malicious Wrapper Packages on npm

The Socket Research Team breaks down a malicious wrapper package that uses obfuscation to harvest credentials and exfiltrate sensitive data.

Powerful Incremental Type-driven Settings Engine.

npm add setset

Also, ensure that strict mode compiler option is enabled in your tsconfig.json. Without it the type-safe implementation benefits offered by Setset will be lost!

Setset is a generic TS library for managing settings. It technically works with JS but is designed to be used with TS as you will see below. Here is an overview of its features:

Setset is designed with the following workflow in mind:

Firstly, you are building some kind of library or framework that has settings that you want your users to be able to control.

You define a TS type representing the input your users will be able to give to configure the settings of your tool.

type Input = {

/**

* Foo bar qux ...

*/

foo?: number

/**

* Abba rabba kadabba ...

*/

bar?: string

/**

* Toto robo mobo ...

*/

qux?:

| boolean

| {

a?: 'Alpha' | 'Bravo'

b?: boolean

}

}

It is desirable to define Input manually (as opposed to relying on e.g. inference) because this way you can write jsDoc. This is important. It can help save your users a trip to the website/README/etc.

You feed this TS type to the type variable in Setset.create and based on the resulting inference implement your settings in a type-safe way.

import * as Setset from 'setset'

const settings = Sestset.create<Input>({

// The implementation below is type-safe, with nuanced

// requirements that match however you have designed

// your Input type.

fields: {

foo: {

initial: () => 1

},

bar: {

initial: () => '?'

},

qux: {

shorthand: (b) => ({ b })

fields: {

a: {

initial: () => 'Bravo'

},

b: {

initial: () => false

}

}

}

}

})

Setset.create returns a settings manager. You expose this API to your users however you want. Maybe the whole api but maybe only a part of it, wrapped, whatever.

settings.data // { foo: 1, bar: '?', qux: { a: 'Bravo', b: false }}

settings.change({ foo: 2 })

settings.data.foo // { foo: 2 }

settings.metadata.fields.foo.value // 2

settings.metadata.fields.foo.initial // 1

Setset has three categories of settings: leaf, namespace, and record.

Leaf settings are terminal points in your settings. When a leaf is changed it overwrites whatever the value was previously.

Namespace settings contain additional settings. Namespaces are useful to provide logical grouping to help users navigate and understand your settings. As you would expect changes to namespaced fields merge with the previous state of the namespace.

Record settings look similar to namespace settings but there are two differences. First, instead of fields we say it has keys and keys are dynamic because they are semantically part of the data. Second, values are of a single type. We refer to a pair of key and value as an entry. Records are useful as an alternative to arrays when keying by one of the member properties makes sense. Doing so enforces uniqueness and allows your users to take advantage of the incremental change API (changes to entries merge with previous entry state, if any).

Setset makes a distinction between settings input and settings data. Input is what users give but data is what is stored. Usually settings input is not 1:1 with the data. Here are some reasons:

The separation between input and data is modeled via type generics on the Setset.create constructor.

type Input = { a?: string }

type Data = { a: string }

const settings = Setset.create<Input, Data>(...)

Because the pattern of optional input with required data is so common it is the default. You can construct your settings with just the input type and Setset will infer a data type where all settings fields (recursively) are required. So for example the above could be rewritten like so and mean the same thing:

type Input = { a?: string }

const settings = Setset.create<Input>(...)

If you only want to tweak the Data type but otherwise use the inferred type, you can achieve this with the InferDataFromInput utility type. For example:

import * as Setset

type Input = { a?: string }

type Data = Setset.InferDataFromInput<Input> & { custom: string }

const settings = Setset.create<Input, Data>(...)

Intersection types have some limitations. For example they cannot turn required properties into optional ones. Look to libraries like type-fest or the builtin utility types Pick Omit etc. to slice and dice as you need in combination with InferDataFromInput.

create

InferDataFromInput

Leaf

Invoke create() to create a new settings instance. There are two type parameters, one required, one optional. The first is Input which types the shape of the input your settings will accept in the .change(...) instance method. The second is Data which types the shape of the settings data in .data instance property. Data type parameter is optional. By default it is inferred from the Input parameter using the following transformations:

Then you must supply the actual implementation. Implementing the settings is a core aspect of using Setset. Each kind of setting (leaf, namespace, record) is documented in its own guide below. The implementation includes things like field initializers and shorthands.

const settings = Setset.create<{ a?: 1 }>({ fields: { a: { initial: () => 0 } } })

See guide section on Input vs Data.

See guide section on leaves.

Setset InstanceThe Setset instance has a handful of methods and properties and is generally what your users will encounter directly or indirectly (see section on API wrapping).

These are the properties and methods at a glance. The following sub-sections go into more detail.

.data

.metadata

.original

.change()

.reset()

The .data property contains the current state of the settings. This property's value will mutated when .change() is invoked. The type of .data is the Data type variable (generic) passed (or inferred when not passed) to Setset.create<Input, Data>.

const settings = Setset.create<{ a?: 1 }>({ fields: { a: { initial: () => 0 } } })

settings.data.a // 0

Invoke .change() to change the current state of settings. The type of the input parameter is the Input type variable (generic) passed to Sestset.create<Input>. Invocations will mutate the .metadata and .data properties.

const settings = Setset.create<{ a?: 1 }>({ fields: { a: { initial: () => 0 } } })

settings.data.a // 0

settings.change({ a: 1 })

settings.data.a // 1

Invoke .reset() to reset the state of .data and .metadata on the current settings instance.

import * as Assert from 'assert'

const settings = Setset.create<{ a?: 1 }>({ fields: { a: { initial: () => 0 } } })

settings.change({ a: 1 })

settings.reset()

Assert.deepEqual(

setters.data,

Setset.create<{ a?: 1 }>({ fields: { a: { initial: () => 0 } } })

)

The .metadata property conatins a representation of the .data with additonal information about the state:

initial means by the initializer (aka. default). change means by an invocation to .change().const settings = Setset.create<{ a?: 1 }>({ fields: { a: { initial: () => 0 } } })

settings.metadata // { type: "leaf", value: 0, from: 'initial', initial: 0 }

settings.change({ a: 1 })

settings.metadata // { type: "leaf", value: 1, from: 'change', initial: 0 }

The .original property contains a representation of the .data as it was just after the instance was first constructed. This is a convenience property derived from the more complex .metadata property.

In your use-case your users might not need the full power of Setset and thus you might choose to only expose a subset of the API. This is completely valid. For example:

import * as Setset from 'setset'

export type Settings = {

// ...

}

export function createMyThing() {

const settingsManager = Setset.create<Settings>({})

// ...

return {

changeSettings: settingsManager.change,

// ...

}

}

Leaves are the building block of settings. They are terminal points representing a concrete setting. This is in contrast to namespaces or records which contain more settings within.

All JS scalar types are considered leaf settings as are instances of a well known classes like Date or RegExp.

type Input = { foo: string; bar: RegExp; qux: Date }

const settings = Setset.create<Input>({ fields: { foo: {}, bar: {}, qux: {} } })

settings.change({ foo: 'bar', bar: /.../, qux: new Date() })

You can force Setset to treat anything as a leaf by wrapping it within the Leaf type. These are called synthetic leves. For example here is how Setset reacts to a Moment instance by default. It treats it as a namespace and expects all the methods on the Moment class to be implemented as settings.

import * as Moment from 'moment'

type Input = { startOn: Moment }

const settings = Setset.create<Input>({ fields: { startOn: { fields: {} } } })

Type '{}' is missing the following properties from type '...': format, startOf, endOf, add, and 78 more

Now here it is fixed via the Leaf type. Notice that the types in .change() and .data only deal with Moment types like you would expect (Leaf has been stripped).

import * as Moment from 'moment'

type Input = { startOn: Setset.Leaf<Moment> }

const settings = Setset.create<Input>({ fields: { startOn: {} } })

settings.change({ startOn: Moment.utc() })

settings.data.startOn.format()

If you try to apply Leaf to a type Setset already considers a leaf natively you'll get a nice little string literal error message. Example:

type Input = { foo: Setset.Leaf<string> }

const settings = Setset.create<Input>({ fields: { foo: {} } })

settings.change({

// Setset makes the type of `foo` be literally this string literal

foo: 'Error: You wrapped Leaf<> around this field type but Setset already considers it a leaf.',

})

Usually you want your input settings to be optional with good defaults as that provides for a better developer experience. An optional input looks like this:

type Input = { foo?: string }

Remember that Setset infers the Data type by default, and remember one of the transformations performed to achieve this is making all settings required. Therefore, by default, Setset will require optional Inputs to have an initializer, like so:

Setset.create<Input>({ fields: { foo: { initial: () => '' } } }).data.foo // guaranteed string

If Setset didn't require the initializer for foo here then you would be exposed to a runtime error because .data.foo type would appear to be string while at runtime actually being string | undefined.

If you explicitly mark your settings data type as optional, then a few things happen. Let's take a look.

type Data = { foo?: string }

Setset.create<Input, Data>({ fields: { foo: { initial: () => '' } } }) // 1

Setset.create<Input, Data>({ fields: { foo: { initial: () => undefined } } }) // 2

Setset.create<Input, Data>({ fields: { foo: {} } }) // 3

.data.foo remains undefined | string since that is what your Data type says.undefined (aka. simply not return). This might be handy if your initializer has some dynamic logic that only conditionally returns a value.Here are the possible states at a glance:

| Input Required | Data Required | Initializer |

|---|---|---|

| Y | N | Forbidden |

| Y | Y | Forbidden |

| N | Y | Required |

| N | N | Optional & may return undefined |

Fixups are small tweaks to inputs that allow them to be correctly stored. A use-case might be that a URL should have a trailing slash, or an protocol (http://) prefix.

Here is an example that makes relative paths explicit:

Setset.create<{ path?: string }>({

fields: {

path: {

fixup(path) {

return path.match('^(./|/).*')

? null

: { value: `./${path}`, messages: ['Please supply a "./" prefix for relative paths'] }

},

default: './',

},

},

})

Notice how null is returned when there is no work to do. In that case Setset will perform no fixups and use the value as was. As you can see when a fixup is needed, it is specified as a structured object. value is the new value to use. messages is an array of string you can use to explain the fixups that were run (more about this in a moment).

If you intend the fixup to be silent, then omit the messages property. If there is a chance that the fixup could surprise a user you should provide a message about it. This will lead to a better developer experience (principal of least surprise).

Fixups are different than validators (see below) because they won't throw an error. Instead the mesages you provide will be logged for the developer to see. If you wish to customize this behaviour then you can pass a custom event handler like so:

Setset.create<{ path?: string }>({

onFixup(info, originalHandler) {

myCustomLogger.say(

`Your setting "${info.path}" was fixed from value ${info.before} to value ${

info.after

} for the following reasons:\n - ${info.messages.join('\n - ')}`

)

},

// ...

})

As you can see the custom handler you provide has access to the fixup info and the original handler. You can pass the info directly to the original handler to achieve what Setset does by default.

The fixup event handler is called any time a fixup is run due to a change. Fixups do not run against your initializers since doing so could trigger warnings that are not actionable by the developer. So always make your own initializers conform their respective fixups, if any.

Validators are was to ensure the integrityof some scalar. A classic example is ensuring a string matches some regular expression.

Validators exist only for leaves and they only execute in the scope of single leaves. That it, it is not possible to build cross-leaf logic such as "if 'a' setting is 'x' then 'b' setting must conform to 'z'".

Validators return null if validation passes. Otherwise they return a failure object. A failure object contains a reasons property where one or multiple reasons for validation failure should be given. For example:

const settings = Setset.create<{ foo?: string }>({

fields: {

foo: {

validate(input, failures) {

const reasons = []

if (!input.length < 1) reasons.push('Cannot be empty')

if (!input.match(/qux/)) reasons.push("Must match pattern 'qux'")

return reasons.length ? { reasons } : null

},

},

},

})

When validation fails an error will be thrown immediately containing the given reasons as well as context about the setting that failed validation. For example:

settings.change({ foo: 'bar' })

Your setting "foo" failed validation with value '':

- Cannot be empty

- Must match pattern 'qux'

As you have seen leaves support multiple methods. Here is the order of their execution. You run as a pipeline, each reciving input from previous.

Note that initialize is not run here because initializers do not run through fixups or validators.

Namespaces have the concept of shorthands. Shorthands are leaves that expand into the namespace fields somehow. They improve the developer experience of setting settings by allowing for the most common field to be hoisted up and not require the extra level of setting nesting. For example here is a classic case with a feature toggle (Note: type anotations written explicitly for clarity purposes here, but in practice you wouldn't, they are automatically inferred):

const settings = Setset.create<{ foo?: boolean | { enabled?: boolean } }>({

fields: {

foo: {

shorthand: (enabled: boolean) => ({ enabled }),

fields: {

enabled: { initial: () => true },

},

},

},

})

settings.change({ foo: false }) // shorthand

settings.change({ foo: { enabled: false } }) // longhand

When implementing shorthands you receive the non-namespace input. This means for example you can have unions.

Setset.create<{ path?: RegExp | string | { prefix?: RegExp | string } }>({

fields: {

path: {

shorthand: (prefix: RegExp | string): { prefix?: RegExp | string } => ({ prefix }),

fields: {

prefix: { initial: () => '' },

},

},

},

})

Further, shorthands can have their input map to multiple namespace fields. For example:

Setset.create<{ foo?: string | { bar?: string; qux?: string; rot?: number } }>({

fields: {

path: {

shorthand: (foo: string): { bar?: string; qux?: string; rot?: number } => ({

bar: foo,

qux: foo.slice(1),

}),

fields: {

bar: { initial: () => '' },

qux: { initial: () => '' },

},

},

},

})

If certain namespace fields are required then shorthands are required to expand into them. For example:

Setset.create<{ foo: string | { bar: string; qux?: string } }>({

fields: {

path: {

shorthand: (foo: string): { bar: string; qux?: string } => ({

bar: foo, // field required

}),

fields: {

qux: { initial: () => '' },

},

},

},

})

Synthetic leaves are supported when you need Setset to treat an object as not a namespace.

import * as Moment from 'moment'

Setset.create<{ foo: Leaf<Moment.Moment> | { bar: string; qux?: string } }>({

fields: {

path: {

shorthand: (foo: string): { bar: string; qux?: string } => ({

bar: foo, // field required

}),

fields: {

qux: { initial: () => '' },

},

},

},

})

This is an esoteric feature, you usually won't need it.

Like leaves, namespaces can have initializers. The reason for this is basically an edge-case: when namespaces are optional in input, required in data, and contain 1+ required fields. In such a case, the only way to maintain all the guarantees is to provide an initializer for the namespae that returns initial values for the required fields of the namespace. The value of supporting this is fairly abstract (again, an edge-case really) but basically Setset allows you to enode a pattern wherin your users would have to either not supply the namespae at all, or, supply it and be forced to also supply some subset of the fields. Why forcing them to supply values when you are able to provide defaults for them anywys via the namespace initializer is unclear, but none the less this is a possible pattern that Setset handles for you for completness sake of the possible ways you conigure your input/data types, if nothing else.

Here is an example:

const settings = Setset.create<{ bar?: number; foo?: { a: string; b: string; c?: number } }>({

fields: {

bar: {

initial: () => 0,

},

foo: {

initial: () => ({ a: '', b: '' }),

fields: { a: {} },

},

},

})

In practice a user would have two choices when interacting with these settings:

// leave "foo" to its default`

settings.change({ bar: 10 })

// configure "foo", forced to address "foo.a" & "foo.b"`

settings.change({ foo: { a: '...', b: '...' } })

If the namespace supports shorthands then its initializer can return values of that form too. For example the previous example revised:

Setset.create<{ foo?: string | { a: string } }>({

fields: {

foo: {

initial: () => '',

shorthand: (a) => ({ a }),

fields: { a: {} },

},

},

})

Namespace initializers are forbidden from returning fields that are optional. Since they are optional they will already have their own local initializers (again unless the underlying data is optional). For example:

Setset.create<{ foo?: { a: string; b?: number } }>({

fields: {

foo: {

initial: () => ({ a: '' }),

fields: { a: {}, b: { initial: () => 0 } },

},

},

})

Luckily you don't need to remember this as Setset's static typing will guide you here.

Note however that, due to a current TypeSript limitation, specifying the extra

b: 0property initializer at the namespace level will not raise a static error. We hope TS will improve in this regard in the future. Luckily the following two things should keep you on track.

- At runtime the local initializers will "win" against any incorret fields at the namespace-level initializer.

- Local initializers will often be statically required which may help you to remember that they shouldn't be at the namespace level.

A confusing but rare case would be optional local initializer that you have not set, and a namespace initializer with field that you have set. This would work at runtime, but incidentally, basically by virtue of a bug.

Like with leaves, if the namespace in the underlying data is optional then the initializer becomes optional too, and may return undefined. For example:

Setset.create<{ foo?: { a: string } }, { foo?: { a: string } }>({

fields: {

foo: {

// this initializer could be omitted, too

initial: () => (Math.random() > 0.5 ? { a: '' } : undefined),

fields: { a: {} },

},

},

})

If the Namespace fields are all optional, then the namespace initializer is forbidden. For example:

Setset.create<{ foo?: { a?: string; b?: number } }>({

fields: {

foo: {

fields: {

a: { initial: () => '' },

b: { initial: () => 0 },

},

},

},

})

Unfortunately the static enforcement here falls down for the same issue as before, TS's lack of complete excess-property check support. This means for now you can supply a

foo.initialmethod and Setset won't be able to raise a static error about it.

Like for leaves, here is a table showing the different states where initializer is valid:

| Input Required | 1+ fields Required | Data Required | Initializer |

|---|---|---|---|

| Y | N | Y || N | Forbidden |

| Y | Y | Y || N | Forbidden |

| N | Y | Y | Required |

| N | Y | N | Optional & may return undefined |

| N | N | Y | Optional & may return undefined |

Sometimes the settings input has fields that are not in the settings data, or vice-versa, or field types differ, or some combination of these things. In any case the result is that Setset requries you to provide a mapper. Mappers are functions you provide that accept the input and some context data and must return the settings data which is has no corrolarry in the settings input.

Mappers are a convenience. Setset could work without them by forcing you to have identical input and data types. But Setset tries to provide some facility so that you don't have to leave the abstraction for the common cases. Setset's data mapping system does not account for every possibility. If it doesn't work for your use-case then just keep your Setset input/data types the same and keep data mapping logic elsewhere in your codebase. While not ideal, it will work.

The mapping system works as follows:

The settings input that mappers receive in their first parameter (more on that below) is normalized settings input. This means shorthands have been expanded, initializers run, and so on.

Mappers do not exist for leaves. This is becaus it is thought to be too restrictive. A namespace-level mapper receives more context and so has more flexibility about how to implement the data mapping. For example maybe two input settings fuse into one data setting after some conditional transformations.

Mapping only works downwardly. This means the mapper function kicks in at the namespace level where fields are diverging; It receives the namespace field inputs (and their descendants) as the first parameter; It must return a value matching the type of the namespace in the data whose fields don't match with the input type. Take this divergence for example:

type Input = { foo?: { bar?: { a?: number; b?: string; c?: boolean } } }

type Data = { foo: { bar: { a: number; b: string; d: boolean } } }

The mapper is supplied like so. We've made the type annotation explicit so you can see what the types flowing are, but note, these are inferred automatically.

Setset.create<Input, Data>({

fields: {

foo: {

fields: {

bar: {

map: (input: { a: number; b: string; c: boolean }): { d: boolean } => ({...}),

fields: {

a: { ... },

b: { ... },

c: { ... },

}

}

}

},

},

})

Setset only considers the first divergence. For example here's the above example tweaked so that the namespace field itself also requires mapping. Note how there is no longer any need to do the mapping on fields.foo.fields.bar. And note the change in the mapper's parameter and return types.

type Input = { foo?: { bar1?: { a?: number; b?: string; c?: boolean } } }

type Data = { foo: { bar2: { a: number; b: string; d: boolean } } }

Setset.create<Input, Data>({

fields: {

foo: {

map: (input: { bar1: { a: number; b: string; c: boolean }}): { bar2: { a: number; b: string; d: boolean } } => ({...}),

fields: {

bar1: {

fields: {

a: { ... }

b: { ... }

c: { ... }

}

}

}

},

},

})

You can think of the root settings like an anonymous namespace. And so the rules we've shown apply just as well there. For example:

type Input = { foo?: string }

type Data = { bar: number }

Setset.create<Input, Data>({

map: (input: { foo: string }): { bar: number } => ({...}),

fields: { foo: {...} },

})

The Mapper's return value is merged shallowly into the namespace.

Sometimes you will want some initial entries to be in the record. To achieve this you can supply an initializer. For example:

type AThing = { b?: number }

type Input = {

a: {

foo?: AThing

[key: string]: AThing | undefined

}

}

const settings = Setset.create<Input>({

fields: {

a: {

initial() {

return { foo: { b: 2 } }

},

entry: { fields: { b: {} } },

},

},

})

settings.data.a.foo // { b: 2 }

Like leaves, record metadata captures the initial state of the record. This doesn't happy with namespaes since namespaces aren't themselves data. But records are. For example (continuing from the previous example):

settings.change({ a: { foo: { b: 10 }, bar: { b: 1 } } })

settings.metadata.a

// {

// type: 'record',

// from: 'change',

// value: {

// foo: { type: 'namespace', fields: { b: { type: 'leaf', from: 'change', value: 10, initial: 2 } } }

// bar: { type: 'namespace', fields: { b: { type: 'leaf', from: 'change', value: 1, initial: undefined } } }

// },

// initial: {

// foo: { type: 'namespace', fields: { b: { type: 'leaf', from: 'change', value: 2, initial: 2 } } }

// }

// }

You aren't forced to leverage the incremental API of Setset. If you just want classical one-time constructor with Setset benefits like automatic environment variable consumption (future feature), you can use Setset like so:

import * as Setset from 'setset'

type Input = { ... }

class {

constructor(input: Input) {

const settings = Setset.create<Input>({...}).change(options).data

}

}

You might have a required setting and be happy to stick with the defaults. You might then notice and be confused by the fact that Setset still requires you to pass an empty configuration object for the setting, like so:

import * as Setset from 'setset'

type Settings = {

foo: string

}

const settings = Setset.create<Settings>({

fields: {

foo: {}, // <-- why is this needed??

},

})

TODO explain this

$initial magic var to reset settting to its original state; re-running initializers if any or just reverting to undefined.create from .initialize stepsFAQs

Powerful Incremental Type-driven Settings Engine.

We found that setset demonstrated a not healthy version release cadence and project activity because the last version was released a year ago. It has 1 open source maintainer collaborating on the project.

Did you know?

Socket for GitHub automatically highlights issues in each pull request and monitors the health of all your open source dependencies. Discover the contents of your packages and block harmful activity before you install or update your dependencies.

Security News

Research

The Socket Research Team breaks down a malicious wrapper package that uses obfuscation to harvest credentials and exfiltrate sensitive data.

Research

Security News

Attackers used a malicious npm package typosquatting a popular ESLint plugin to steal sensitive data, execute commands, and exploit developer systems.

Security News

The Ultralytics' PyPI Package was compromised four times in one weekend through GitHub Actions cache poisoning and failure to rotate previously compromised API tokens.