Security News

Research

Data Theft Repackaged: A Case Study in Malicious Wrapper Packages on npm

The Socket Research Team breaks down a malicious wrapper package that uses obfuscation to harvest credentials and exfiltrate sensitive data.

Base builtin tools make and transform data object layers (dols).

The main idea comes in many names such as

Data Access Object (DAO),

Repository Pattern,

Hexagonal architecture, or ports and adapters architecture

for data.

But simply put, what dol provides is tools to make your interface with data be domain-oriented, simple, and isolated from the underlying data infrastucture. This makes the business logic code simple and stable, enables you to develop and test it without the need of any data infrastructure, and allows you to change this infrastructure independently.

The package is light-weight: Pure python; no third-party dependencies.

To install: pip install dol

Say you have a source backend that has pickles of some lists-of-lists-of-strings,

using the .pkl extension, and you want to copy this data to a target backend,

but saving them as gzipped csvs with the csv.gz extension.

We'll first work with dictionaries instead of files here, so we can test more easily, and safely.

import pickle

src_backend = {

'file_1.pkl': pickle.dumps([['A', 'B', 'C'], ['one', 'two', 'three']]),

'file_2.pkl': pickle.dumps([['apple', 'pie'], ['one', 'two'], ['hot', 'cold']]),

}

targ_backend = dict()

Here's how you can do it with dol tools

from dol import ValueCodecs, KeyCodecs, Pipe

# decoder here will unpickle data and remove remove the .pkl extension from the key

src_wrap = Pipe(KeyCodecs.suffixed('.pkl'), ValueCodecs.pickle())

# encoder here will convert the lists to csv string, the string into bytes,

# and the bytes will be gzipped.

# ... also, we'll add .csv.gz on write.

targ_wrap = Pipe(

KeyCodecs.suffixed('.csv.gz'),

ValueCodecs.csv() + ValueCodecs.str_to_bytes() + ValueCodecs.gzip()

)

# Let's wrap our backends:

src = src_wrap(src_backend)

targ = targ_wrap(targ_backend)

# and copy src over to targ

print(f"Before: {list(targ_backend)=}")

targ.update(src)

print(f"After: {list(targ_backend)=}")

From the point of view of src and targ, you see the same thing.

assert list(src) == list(targ) == ['file_1', 'file_2']

assert (

src['file_1']

== targ['file_1']

== [['A', 'B', 'C'], ['one', 'two', 'three']]

)

But the backend of targ is different:

src_backend['file_1.pkl']

# b'\x80\x04\x95\x19\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00]\x94(]\x94(K\x01K\x02K\x03e]\x94(K\x04K\x05K\x06ee.'

targ_backend['file_1.csv.gz']

# b'\x1f\x8b\x08\x00*YWe\x02\xff3\xd41\xd21\xe6\xe52\xd11\xd51\xe3\xe5\x02\x00)4\x83\x83\x0e\x00\x00\x00'

Now that you've tested your setup with dictionaries, you're ready to move on to real, persisted storage. If you wanted to do this with local files, you'd:

from dol import Files

src = Files('PATH_TO_LOCAL_SOURCE_FOLDER')

targ = Files('PATH_TO_LOCAL_TARGET_FOLDER)

But you could do this with AWS S3 using tools from s3dol, or Azure using tools from azuredol, or mongoDB with mongodol, github with hubcap, and so on...

All of these extensions provide adapters from various data sources/targets to the

dict-like interface (called "Mapping" in python typing).

What dol provides are base tools to make a path from these to the interface

that makes sense for the domain, or business logic in front of you,

so that you can purify your code from implementation details, and therefore be

create more robust and flexible code as far as data operations are concerned.

Note: This project started as py2store.

dol is the core of py2store has now been factored out

and many of the specialized data object layers moved to separate packages.

py2store is acting more as an aggregator package -- a shoping mall where you can quickly access many (but not all)

functionalities that use dol.

It's advised to use dol (and/or its specialized spin-off packages) directly when the core functionality is all you need.

Storage CRUD how and where you want it.

List, read, write, and delete data in a structured data source/target, as if manipulating simple python builtins (dicts, lists), or through the interface you want to interact with, with configuration or physical particularities out of the way. Also, being able to change these particularities without having to change the business-logic code.

If you're not a "read from top to bottom" kinda person, here are some tips: Quick peek will show you a simple example of how it looks and feels. Use cases will give you an idea of how py2store can be useful to you, if at all.

The section with the best bang for the buck is probably

remove (much of the) data access entropy.

It will give you simple (but real) examples of how to use py2store tooling

to bend your interface with data to your will.

How it works will give you a sense of how it works. More examples will give you a taste of how you can adapt the three main aspects of storage (persistence, serialization, and indexing) to your needs.

Install it (e.g. pip install py2store).

Think of type of storage you want to use and just go ahead, like you're using a dict. Here's an example for local storage (you must you string keys only here).

>>> from py2store import QuickStore

>>>

>>> store = QuickStore() # will print what (tmp) rootdir it is choosing

>>> # Write something and then read it out again

>>> store['foo'] = 'baz'

>>> 'foo' in store # do you have the key 'foo' in your store?

True

>>> store['foo'] # what is the value for 'foo'?

'baz'

>>>

>>> # Okay, it behaves like a dict, but go have a look in your file system,

>>> # and see that there is now a file in the rootdir, named 'foo'!

>>>

>>> # Write something more complicated

>>> store['hello/world'] = [1, 'flew', {'over': 'a', "cuckoo's": map}]

>>> stored_val = store['hello/world']

>>> stored_val == [1, 'flew', {'over': 'a', "cuckoo's": map}] # was it retrieved correctly?

True

>>>

>>> # how many items do you have now?

>>> assert len(store) >= 2 # can't be sure there were no elements before, so can't assert == 2

>>>

>>> # delete the stuff you've written

>>> del store['foo']

>>> del store['hello/world']

QuickStore will by default store things in local files, using pickle as the serializer.

If a root directory is not specified,

it will use a tmp directory it will create (the first time you try to store something)

It will create any directories that need to be created to satisfy any/key/that/contains/slashes.

Of course, everything is configurable.

py2store provides tools to create the dict-like interface to data you need.

If you want to just use existing interfaces, build on it, or find examples of how to make such

interfaces, check out the ever-growing list of py2store-using projects:

pandas.DataFrame from various sourcesJust for fun projects:

grub.How many times did someone share some data with you in the form of a zip of some nested folders whose structure and naming choices are fascinatingly obscure? And how much time do you then spend to write code to interface with that freak of nature? Well, one of the intents of py2store is to make that easier to do. You still need to understand the structure of the data store and how to deserialize these datas into python objects you can manipulate. But with the proper tool, you shouldn't have to do much more than that.

Ever have to switch where you persist things (say from file system to S3), or change the way key into your data, or the way that data is serialized? If you use py2store tools to separate the different storage concerns, it'll be quite easy to change, since change will be localized. And if you're dealing with code that was already written, with concerns all mixed up, py2store should still be able to help since you'll be able to more easily give the new system a facade that makes it look like the old one.

All of this can also be applied to data bases as well, in-so-far as the CRUD operations you're using are covered by the base methods.

Shinny new storage mechanisms (DBs etc.) are born constantly, and some folks start using them, and we are eventually lead to use them as well if we need to work with those folks' systems. And though we'd love to learn the wonderful new capabilities the new kid on the block has, sometimes we just don't have time for that.

Wouldn't it be nice if someone wrote an adapter to the new system that had an interface we were familiar with? Talking to SQL as if it were mongo (or visa versa). Talking to S3 as if it were a file system. Now it's not a long term solution: If we're really going to be using the new system intensively, we should learn it. But when you just got to get stuff done, having a familiar facade to something new is a life saver.

py2store would like to make it easier for you roll out an adapter to be able to talk to the new system in the way you are familiar with.

You have a new project or need to write a new app. You'll need to store stuff and read stuff back. Stuff: Different kinds of resources that your app will need to function. Some people enjoy thinking of how to optimize that aspect. I don't. I'll leave it to the experts to do so when the time comes. Often though, the time is later, if ever. Few proof of concepts and MVPs ever make it to prod.

So instead, I'd like to just get on with the business logic and write my program. So what I need is an easy way to get some minimal storage functionality. But when the time comes to optimize, I shouldn't have to change my code, but instead just change the way my DAO does things. What I need is py2store.

Data comes from many different sources, organization, and formats.

Data is needed in many different contexts, which comes with its own natural data organization and formats.

In between both: A entropic mess of ad-hoc connections and annoying time-consuming and error prone boilerplate.

py2store (and it's now many extensions) is there to mitigate this.

The design gods say SOC, DRY, SOLID* and such. That's good design, yes. But it can take more work to achieve these principles. We'd like to make it easier to do it right than do it wrong.

(*) Separation (Of) Concerns, Don't Repeat Yourself, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/SOLID))

We need to determine what are the most common operations we want to do on data, and decide on a common way to express these operations, no matter what the implementation details are.

Looking at this, we see that the base operations for complex data systems such as data bases and file systems overlap significantly with the base operations on python (or any programming language) objects.

So we'll reflect this in our choice of a common "language" for these operations. For examples, once projected to a py2store object, iterating over the contents of a data base, or over files, or over the elements of a python (iterable) object should look the same, in code. Achieving this, we achieve SOC, but also set ourselves up for tooling that can assume this consistency, therefore be DRY, and many of the SOLID principles of design.

Also mentionable: So far, py2store core tools are all pure python -- no dependencies on anything else.

Now, when you want to specialize a store (say talk to data bases, web services, acquire special formats (audio, etc.)), then you'll need to pull in a few helpful packages. But the core tooling is pure.

By store we mean key-value store. This could be files in a filesystem, objects in s3, or a database. Where and how the content is stored should be specified, but StoreInterface offers a dict-like interface to this.

__getitem__ calls: _id_of_key _obj_of_data

__setitem__ calls: _id_of_key _data_of_obj

__delitem__ calls: _id_of_key

__iter__ calls: _key_of_id

>>> from dol import Store

A Store can be instantiated with no arguments. By default it will make a dict and wrap that.

>>> # Default store: no key or value conversion ################################################

>>> s = Store()

>>> s['foo'] = 33

>>> s['bar'] = 65

>>> assert list(s.items()) == [('foo', 33), ('bar', 65)]

>>> assert list(s.store.items()) == [('foo', 33), ('bar', 65)] # see that the store contains the same thing

Now let's make stores that have a key and value conversion layer input keys will be upper cased, and output keys lower cased input values (assumed int) will be converted to ascii string, and visa versa

>>>

>>> def test_store(s):

... s['foo'] = 33 # write 33 to 'foo'

... assert 'foo' in s # __contains__ works

... assert 'no_such_key' not in s # __nin__ works

... s['bar'] = 65 # write 65 to 'bar'

... assert len(s) == 2 # there are indeed two elements

... assert list(s) == ['foo', 'bar'] # these are the keys

... assert list(s.keys()) == ['foo', 'bar'] # the keys() method works!

... assert list(s.values()) == [33, 65] # the values() method works!

... assert list(s.items()) == [('foo', 33), ('bar', 65)] # these are the items

... assert list(s.store.items()) == [('FOO', '!'), ('BAR', 'A')] # but note the internal representation

... assert s.get('foo') == 33 # the get method works

... assert s.get('no_such_key', 'something') == 'something' # return a default value

... del(s['foo']) # you can delete an item given its key

... assert len(s) == 1 # see, only one item left!

... assert list(s.items()) == [('bar', 65)] # here it is

>>>

We can introduce this conversion layer in several ways.

Here are few...

>>> # by subclassing ###############################################################################

>>> class MyStore(Store):

... def _id_of_key(self, k):

... return k.upper()

... def _key_of_id(self, _id):

... return _id.lower()

... def _data_of_obj(self, obj):

... return chr(obj)

... def _obj_of_data(self, data):

... return ord(data)

>>> s = MyStore(store=dict()) # note that you don't need to specify dict(), since it's the default

>>> test_store(s)

>>>

>>> # by assigning functions to converters ##########################################################

>>> class MyStore(Store):

... def __init__(self, store, _id_of_key, _key_of_id, _data_of_obj, _obj_of_data):

... super().__init__(store)

... self._id_of_key = _id_of_key

... self._key_of_id = _key_of_id

... self._data_of_obj = _data_of_obj

... self._obj_of_data = _obj_of_data

...

>>> s = MyStore(dict(),

... _id_of_key=lambda k: k.upper(),

... _key_of_id=lambda _id: _id.lower(),

... _data_of_obj=lambda obj: chr(obj),

... _obj_of_data=lambda data: ord(data))

>>> test_store(s)

>>>

>>> # using a Mixin class #############################################################################

>>> class Mixin:

... def _id_of_key(self, k):

... return k.upper()

... def _key_of_id(self, _id):

... return _id.lower()

... def _data_of_obj(self, obj):

... return chr(obj)

... def _obj_of_data(self, data):

... return ord(data)

...

>>> class MyStore(Mixin, Store): # note that the Mixin must come before Store in the mro

... pass

...

>>> s = MyStore() # no dict()? No, because default anyway

>>> test_store(s)

>>> # adding wrapper methods to an already made Store instance #########################################

>>> s = Store(dict())

>>> s._id_of_key=lambda k: k.upper()

>>> s._key_of_id=lambda _id: _id.lower()

>>> s._data_of_obj=lambda obj: chr(obj)

>>> s._obj_of_data=lambda data: ord(data)

>>> test_store(s)

FAQs

Base builtin tools make and transform data object layers (dols).

We found that dol demonstrated a healthy version release cadence and project activity because the last version was released less than a year ago. It has 1 open source maintainer collaborating on the project.

Did you know?

Socket for GitHub automatically highlights issues in each pull request and monitors the health of all your open source dependencies. Discover the contents of your packages and block harmful activity before you install or update your dependencies.

Security News

Research

The Socket Research Team breaks down a malicious wrapper package that uses obfuscation to harvest credentials and exfiltrate sensitive data.

Research

Security News

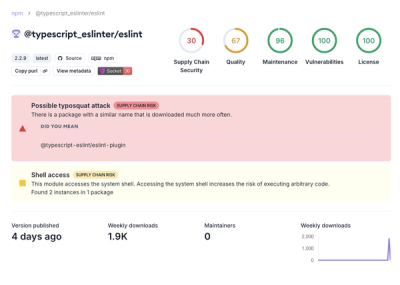

Attackers used a malicious npm package typosquatting a popular ESLint plugin to steal sensitive data, execute commands, and exploit developer systems.

Security News

The Ultralytics' PyPI Package was compromised four times in one weekend through GitHub Actions cache poisoning and failure to rotate previously compromised API tokens.